Arthur Danto, “The Artworld”

The Search for Signs of Intelligent

Life in the Universe

Danto’s Answer to the Conundrum

Imitation

Theory and Reality Theory

The “is” of Artistic Identification

Arthur Danto, “The Artworld”, ABQ

Chapter 3, pp. 33-44

Arthur Coleman Danto (1924 – 2013)

Hamlet

ACT III SCENE IV

|

HAMLET: |

Do you see nothing there? |

|

QUEEN GERTRUDE |

Nothing at all; yet all that is I see. |

·

In

order that anything be art, a theory of art is necessary.

·

This

is revealed by the analysis of visually indiscernible things which are,

nevertheless, different items

·

They

are different because of the “theory” that constitutes them, not by any

intrinsic, visual property

“The Artworld”

In 1964, Danto

wrote “The Artworld”

This essay has

greatly influenced debates about aesthetics and art ever since. In it he was

responding to the monumental changes and innovations he was witnessing in this

and the previous 50 decades.

Preface: Danto

attacks Socrates and Plato’s view of art as imitation (mimesis0 or a mirror. He

calls this the “Imitation Theory” or “IT”. If this were correct, then any

mirror image would also be an artwork, which is obviously false. It’s true that

many artists both at that time and later did try to imitate nature in their

art. But the invention of photography put an end to this as the goal of art,

and showed that the mimesis or imitation view is false.

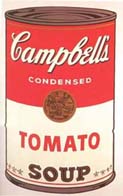

When he visited

Andy Warhol’s exhibition of Brillo Boxes at the Stable Gallery in New York he

asked himself a fundamental question:

What made Warhol’s Brillo Boxes different from commercial Brillo

boxes?

More

specifically, why are Warhol’s Boxes “Art” and the Brillo Company’s boxes are

not?

The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe

|

The Artists: |

|

An

excerpt from the Play:

Here I am, I show'em

this can of Campbell's tomato soup. "This is

soup." "And this is

art." Then I shuffle the two

behind my back. Now what is this? No. I dread having to

explain tartar sauce! |

Danto’s Answer to the Conundrum

Danto’s answer to

this question, “What’s the difference” was “The Art World.”

This is a term he

coined to suggest that it is not possible to understand conceptual art without

the help of the artworld, that is, the community of art interpreters –art critics, art curators, artists, and art collectors

– within the network of galleries, museums and other art “institutions.”

Imitation Theory and Reality Theory

Arthur Danto

published “The Artworld” to explain this philosophical insight gained from artworks.

Dant points to

the need for Theory for something to exist as art. Theory provides us ways of looking at

paintings and regarding them as art. But

if our theories do not match our experiences, then we need new theories. This is analogous to development in the

history of science .

Theory –>

Deviations -> New theory

Danto contrasts

two concepts of “Imitation Theory” (IT) with “Reality Theory” (RT) Recall at this time there was still some

resistance to what was then “avant-garde,” that is to say, non-realistic and

not representational art. Previously, according

to IT, artworks were judged to be artworks only if they were an imitation of

reality.

(‘Imitation Theory’, also

mimesis: the idea that art is imitation of reality),

Danto contrasts

two concepts of “Imitation Theory” (IT) with “Reality Theory” (RT)

Roy Lichtenstein, American

(1923-1997). Ohhh…Alright…, 1964. Oil and Magna on

canvas. 91.4 x 96.5 cm (36 x 38 in). © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Private

Collection.

By contrast, RT

explains that art is something that is original and distinguishable. It can

look like an object that is not art, and therefore it cannot always be easily

recognized as an art object, yet it is easily and correctly recognized and

distinguished from non-art objects by those possessing the pertinent theory and

relevant facts. Danto says:

“According to it (RT), the artists in question were to be

understood not as unsuccessfully imitating real forms but as successfully

creating new ones, quite as real as the forms which the older art had been

thought, in its best examples, to be creditably imitating.”[2]

According to RT,

the acceptance of post-impressionist reveals that art objects are autonomous

things. IT ignores their

reality, concentrating instead on the “real objects” they represent. But for RT, the real painting (or other

object of art) are never ignored. RT

recognizes then canvases covered with paint as canvases covered

with paint. While consideration of the formal elements of

paintings was certainly involved in IT, under RT, it became acceptable to look

at paintings more on the basis of their formal properties, and less on the

basis of the quality of their imitation or representation. Contemporary art, Danto maintains, must be

understood in terms of RT. As an

illustration of how theory makes art possible, he points to Post-impressionist

painting. There could be no such thing

were it not for the RT. It simply would

not be considered art.

It is important

to make a distinction here between:

1. ‘it would not be possible to paint

these images’,

2. ‘it would not be possible for these

paintings to exist qua paintings’.

Certainly such

images could exist, but no one would/could/should related to them

as paintings unless and until equipped with a suitable theoretical framework.

Though it is true of some paintings that they would

not have been made if it were not for the development of certain ideas about

painting, that development possibly motivated by earlier paintings which may or

may not have had an explicit theoretical basis prior to their painting, Danto is

talking about how such paintings are considered, and whether or not they are

taken up into the art world.

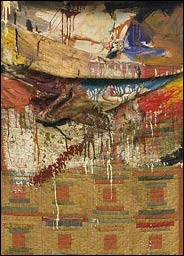

He further makes

his point he cites paradigmatic examples where art objects are

indistinguishable or nearly so from non-art objects. For example genuine beds from those made by

Robert Rauschenberg (an actual bed hung vertically streaked with paint) and

Claes Oldenburg.

The “is” of Artistic Identification

Danto asks how

one can mistake the art for real beds?

This is equivalent to asking what makes them artworks. A naïve person (“Testadura”, Danto calls him) might not realize this is art

and might think it’s just a really messy bed.

To answer his question, he introduces another new term: the “‘is’ of artistic identification.”[3] This ‘is’ is used in sentences like “That a

is b.” where a is some specific physical property or part of an object. It is a necessary condition for something to

be an artwork that is can be the subject of such a sentence. So when I point to a certain dark region of

color in a painting that I say, that is my mother as a small child.” I am using the “is” of artistic

identification.

•

Danto

talks about the “is” at work in works of art.

•

This

bed is an artwork” is like “This blob (in a child’s artwork) is my dog.”

•

It’s

also like saying, of the Brueghel painting “Fall of Icarus,” “This blob of

white paint is Icarus.”

•

Danto

also gives two imaginary examples (top p. 38) of abstract artworks that look

the same but represent two different laws of Newton.

•

Danto

calls the “is” in these examples “the ‘is’ of artistic identification”.

•

We

can’t help the poor naïve guy Testadura understand

why this is art until he “gets” it about this “is”.

Danto shows how

this can make a very big difference in the way one relates to paintings. For instance he imagines the viewing of two

identical paintings (each a white rectangle with a black line through the

center). A hardcore abstractionist might

refuse to identify his black-lined rectangle with anything – “there is nothing

there but white paint and black”. Testadura, who likewise believes that the line represents/

nothing, does not “see” the painting (as an painting) at all.

·

Testadura:

There is no artwork, all he sees is paint

·

The

artist: That black paint is black paint

Danto: “We cannot

help [Testadura] until he has mastered the is of

artistic identification and so constitutes it a work of art” (139)

“To see something as art requires ... an atmosphere of artistic

theory, a knowledge of the history of

art, an artworld.” (140)

“It is the theory that takes it up into the world of art and keeps

it from collapsing into the real object which it is ...

The

abstractionist is employing the ‘is’ of artistic identification, and the

philistine is not.

If someone with

no aesthetic education simply says, “All I see is paint,” it’s just shows that

he fails to grasp artistic identification which will allow him/her to

constitute it a work of art. In pure

abstraction the artist has achieved abstraction through rejection of artistic

identifications, but in fact when Danto says, “That black paint is black paint”

he is not just repeating the obvious but using artistic identification.

“What in the end makes the difference between a Brillo box and a

work of art consisting of a Brillo Box is a certain theory of art. It is the theory that takes it up into the

world of art and keeps it from collapsing into the real object which it is ...

Of course, without the theory, one is unlikely to see it as art ...”

Developments in

modern art, especially post-impressionist paintings, challenged the IT, since

imitation just was not their goal. To explain or show why these new works were

art, a new theory of art was needed. The new theory also worked to make other

things start to count as art, such as masks and weapons from anthropological

museums. This new theory, the “Reality Theory,” or RT, didn’t pretend that

artworks were imitations, it almost threw it in your face that they were not,

since they didn’t look realistic, etc. Robert Rauschenberg’s bed is

BOTH, actual bed, which he hung vertically on a wall and streaked with paint

and an object of art. A naïve person (“Testadura”,

Danto calls him) might not realize this is art and might think it’s just a

really messy bed.

But Testadura’s error is a philosophical one. He thinks the bed

is just a bed, but it’s an artwork. There’s some theory that makes the ordinary

thing into an artwork, just like being alive makes a person into more than

simply their body.

Is of artistic identification

”This bed is an

artwork” is like “This blob (in a child’s artwork) is my dog.” Danto tries to

explain and understand the “is” in these sentences. It’s also like saying, of

the Brueghel painting “Fall of Icarus,” “This blob of white paint is Icarus.”

Danto also gives two imaginary examples (top p. 38) of abstract artworks that

look the same but represent two different laws of Newton. In one painting, the

line in the middle “is” the path of a particle. In the other painting, the two

squares “are” forces pressing against each other. Danto calls the “is” in these

examples “the ‘is’ of artistic identification”. We can’t help the poor naïve

guy Testadura understand why this is art until he

“gets” it about this “is”.

Thus Andy

Warhol’s “Brillo Boxes” look just like actual, ordinary ones. Why are they art?

Each Warhol box “is” more than a regular box; it ‘is’ an artwork, using this

new theory of art. “What in the end makes the difference between a Brillo box

and a work of art consisting of a Brillo Box is a certain theory of art” (p.

41). This couldn’t be art without a lot of both theory and history.

We have a valid

argument

If we have a work of art, then we have theory.

We have no theory.

Therefore

We have no work of art.

His claim is that

it is the work of art (the practice) that implies the theory, not the theory

that implies the work of art.

Danto coined the

term Artworld to suggest that it is not possible to understand conceptual art

without the help of the Artworld. The Artworld is defined in its cultural

context of the definition of art, or as an atmosphere of artistic theory. The

artworld both holds the IT and the RT, but mostly creates

itself in the RT. It created the notion that art is imitation of real objects

yet not objects themselves, also create the ability to discern art from that

which should be considered/ is art that should not be considered

art.

Here Danto

constructs what he calls the “style matrix” for art.

Representational Expressionist

+ + Artwork

is

both Fauvism

+ - Representational,

not expressionist Ingres

- + Epressionist,

not

representational Pollock

- - Artwork

is

neither Pure

Abstraction

Danto’s idea is

that whenever you give a list of the kinds of features or styles that art can

be made in, you also open up the option that someone will just reject those

features. (This is a lot like what Kant meant when he discussed how a genius is

someone who breaks the rules of art, and sets new rules by example.)

For instance, up until the 20th century most

painters thought of a painting as something done on a flat surface. But then

some artists (like Frank Stella) started to make canvases that were shaped or

curved and stuck out of the wall. And others made canvases in zig-zag shapes.

Or, one feature of art used to be that it involved or was made on an object,

like a canvas. But some artists began to make art out of light, so that the

light made shapes and designs. An example is James Turrell with his light

tunnel here in Houston at our Museum of Fine Arts. Another is the

displays of neon lights by Dan Flavin—you can see some at the Menil Collection’s Richmond Center which is in around the

1300 block of Richmond, across from El Pueblito Place

restaurant.

1.

Or,

the avant-garde composer John Cage made musical works that were just periods of

silence, where the musicians would sit there and not move!

Or the avant-garde playwright Peter Handke wrote a play called

“Insulting the Audience” in which the actors came on-stage and did just

that—insulted the audience!

Danto’s point here is that for almost any feature you can think of that seems

to belong to art, some artist is likely to come along and reject it at some

time, for some reason. This can only be true if somehow the artist

is helping create and advance in our theory of the relevant kind of art.