PHI3800 Lecture 5: 20th and 21st Century Theories of Beauty –

The Aesthetic Attitude in the Twentieth Century

Three Versions of the Aesthetic Attitude Theory

1.

The Aesthetic State: Psychical Distance

·

Problems

·

Pros

2.

Aesthetic Awareness: Disinterested Attention

·

Problems

·

Consider

Vivas's Contentions About Literature as Aesthetic Object

#3

Aesthetic Perception: "Seeing As" (Virgil Aldrich)

·

Pros

·

Problems

20th

and 21st Century Theories of Beauty –

George Dickie

Introduction to Aesthetics: An Analytic

Approach[1]

My Chapter 3 Notes

The Aesthetic Attitude in the Twentieth Century

History of the organizing

strain of aesthetics.

“Beauty ended with the introduction of the concept of the

aesthetic.”

Out of the tradition of Schopenhauer there developed

"aesthetic-attitude theories."

Aesthetic Attitude theories claims to give the correct account of the

nature of aesthetic criticism and aesthetic appreciation. One must identify the correct subjective

“attitude” to adopt in order to make possible and aesthetic experience. The object of criticism is held to be "the aesthetic object" and it is

the “phenomenal object” that appears (arises) when one adopts the aesthetic

attitude. (Think of Kant’s disinterested

viewing here.) The attitude theories

have been challenged by "metacriticism."

Note: If being an “aesthetic

object” merely means being the object of someone’s aesthetic attention, then

nearly any object could be an aesthetic object so long as it was attended to in

the right way by someone. Saying that an

object is aesthetic tells you nothing about the object itself (nothing

objective), but only how it is being viewed.

(The ugliest thing in the world can be an aesthetic object.)[2]

Three Versions of the Aesthetic Attitude Theory

1.

Edward Bullough (28 March 1880 – 17 September 1934)

2.

Jerome Stolnitz and Eliseo Vivas.

3.

Virgil Aldrichs

3.

Chapter 4 is devoted to a discussion

and criticism of Monroe Beardsley's metacritical

version of aesthetic object.

From the onset, it should be acknowledged that it is not

completely clear what "attitude" means. Are they for instance “deliberate acts of

conscious will?” Spontaneously arising psychological states of persons? All these views claim that a person can do something (“achieve psychical

distance,” “perceive disinterestedly,” or “see as”) that will change any object

perceived into an aesthetic object.

1.

The Aesthetic State: Psychical Distance

Edward Bullough introduces the concept of psychical distance by using as an example the appreciation of a

natural phenomenon rather than a work of art.

For instance fog at sea can be an aesthetic object.

“Distance is produced in the first

instance by putting the phenomenon, so to speak, out of gear with our

practical, actual self; by allowing it to stand outside the context of our

personal needs and ends—in short, by looking at it objectively," as it has

often been called, by permitting only such reactions on our part as emphasize

the "objective" features of the experience.”

Bullough's account here is reminiscent of Schopenhauer's theory of

the sublime. Schopenhauer speaks of the

forcible detachment of the will (roughly the desires) required for the

appreciation of a sublime and threatening object. Not further, adopting such a perspective

focuses on some qualtieis of the fof

(perhaps its mistiness or mysteriousness) and not

other (that it is very dangerous to be at sea if you can’t see what’s in front

of you.) An inhibition may be induced by

the perceiver or it may be a psychological state into which the perceiver is

induced. Once the state has occurred, an

object can be aesthetically appreciated.

Bullough suggest that there are two ways in which proper psychical

distance can be lost:

1 “under-distancing”

2. “over-distancing”

An example would be of a jealous

husband viewing Othello. He is pre-occupied with his own suspicions

about his wife, so much so, that he cannot aesthetically appreciate the play.

Sheila Dawson, gives as an example

of over-distancing the case in which a person is primarily interested in the

technical details of a performances.

(e.g. the skill of the dancer, or the technique employed by the

painter) This is similar to Alison’s

critique that art criticism can destroy aesthetic experience.

Do we need to postulate a special kind of action called "to

distance" and a special kind of psychological state called "being

distanced" to account for the fact that we can sometimes can appreciate

the aesthetic characteristics of otherwise threatening things? It seems more economical to explain this

phenomenon in terms of attention. You are just “attending” to the fog. There is no virtue in being theoretically

economical if one ignores actual facts, but is seems that we can give an

adequate account of the “facts” of these sorts of appreciations without

positing a special kind of psychological state. The issue presumably has to be settled

introspectively, but Bullough suggests that to view threatening cases

aesthetically requires a mental mechanism to block worries about personal

safety. Dickie grants that there is some

initial plausibility when invoked to dealing with threatening natural objects. But he claims that it has very little

plausibility when it is used to explain our relation to works of art.

The husband who while watching a Othello, preoccupied with

his suspicions about his own wife is not failing to achieve the proper state by

“under-distancing.” Dickie we could more

economically account for this by saying he's simply not paying attention

to the play. One might explain

the audience member who mounts the stage to save the threatened heroine in the

play as one who has “lost psychical distance.”

But a better explanation would be that he has “lost his mind” or that he

is no longer mindful of the rules and conventions that govern theater

situations, in this case the rule that forbids spectators from interfering with

the actions of the actors.

Defenders see psychical distance as the first and key step of an

aesthetic theory, and it is held to have far-reaching implications. If an art work is such as to encourage the

loss of or inability to achieve psychical distance it is considered critically

flawed. Sheila Dawson and Susanne Langer

refer to the scene in “Peter Pan” in which Peter Pan turns to the audience and

asks them to clap their hands in order to save Tinkerbelle's life. They claim that Peter Pan's action destroys

psychical distance (or the necessary illusion).[3] Arlene Croce refused to view a work by

choreographer Bill T. Jones because, as is included many critically ill people

talking and dancing about the real-life illnesses, she claimed she was unable

to achieve a “psychical distance.”[4] For that reason, she maintained, the work was

not really art at all. It has

been crafted in such a way and advertised in such a way that made it impossible

for audience members to engage with it as a work of art.

1. Provides some basis for evaluating works of art.

2. A state of psychical distance

can reveal the properties of a work of

art that properly belong to the aesthetic object as a

aesthetic object (to which we ought

to direct our attention). An also what

properties we ought to screen off such as historical circumstances of the works

creation.

3. Provides substantive guidelines

for art criticism and appreciation.

(However. if no such state exists, it’s got problems)

2.

Aesthetic Awareness: Disinterested Attention

Jerome Stolnitz suggests that the

concept of “the aesthetic” can be defined in terms of disinterested attention. His

is an outgrowth of both the theory of psychical

distance and the notion of disinterestedness.

"psychical distance" names a special action or psychological

state.

"disinterested attention" names the ordinary action of

attending done in a special way.

Two

pairs of concepts:

1. interested/disinterested and

2. interested/ uninterested

The Former: financial interest, partiality and impartiality,

and/or selfishness verses unselfishness

The Latter: Notions of concern and attentiveness verses

indifferent and not attentive to it

If the distinction between the two pairs of notions is preserved,

it can be seen how a person can be both interested in something and be

disinterested concerning that same something at the same time. (For example, a

juror.) Similarly if I was reviewing a

piece of Real Estate and considering it as a possible investment this would not

be a disinterested viewing. This would be interested in the sense that I'm

considering practical game. On the other hand if I'm looking at it merely as an

example of landscape noting the trees the Hills the topography perhaps a patch

of wildflowers in the distance then I am viewing it disinterestedly not for

practical game but attending merely to its formal perceptual qualities and the

enjoyment such attention provides. But

note that I am not uninterested in this patch of real estate. I'm attending to

it closely..

Jerome Stolnitz's definition:

"disinterested (with no ulterior purpose) and sympathetic

attention to and contemplation of any object of awareness whatever, for its own

sake alone."

This is "intransitive" attention.

That is, there is no direct object of the action as the crucial mode of

attention.

If Ann is listening to some music in order to write an analysis of

it, then this is a “non-aesthetic ways of “attending to” etc. (Again, sort of

like Allison’s contention that criticism destroys aesthetic appreciation.) Accordingly, a work of art or a natural

object may or may not be an aesthetic object, depending on whether or not it is

attended

to disinterestedly. Central to

the theory is the notion that there are at least two distinguishable kinds

of attention and that the concept of “the aesthetic” can be defined in

terms of one of them.

But perhaps we can account for aesthetic phenomena more

economically with only one kind of attention.

Cases of alleged non-disinterested attention turn out to be cases of inattention according to Dickie. If so, then there is no reason to think that

there is more than one kind of attention involved. Also, while it is easy enough to see what it

means to have different motives for attending to an object, it is not

so easy to see how having different motives affects the nature of attention. Different motives may direct attention to

different aspects of the objects, but the activity of attention itself remains

the same.[5]

Another Issue arises: The question arises however as to whether a

fully disinterested attention can be conceptual or not. The application of concepts

such as that the auditory object of my attention is produced by an English horn

or a French Horm or that is a violin might one might say, be a interested

judgment rather than a disinterested appreciation. One might argue that a fully disinterested

appreciation of a phenomenological moment requires restricting one’s attention

to the immediately perceptible qualities without going on to make judgments

about what was the origins of those phenomenological qualities. But that in turn suggests that disinterested

awareness is very rare. It's not clear

how to separate listening to music and not interpreting the music as sourced by

particular musical instruments could be.

Consider

Vivas's contentions about literature as aesthetic object:

Vivas claims that his conception of the “aesthetic appreciation”

posits "that The Brothers Karamazov

can hardly be read as art," probably because one can hardly avoid reading

it as social criticism to some extent, which is one of the ways that Vivas

mentions literature is attended to non-aesthetically.

But this seems a counter-example; any theory that claims this (i.e "that The

Brothers Karamazov can hardly be read as art.") must surely be

suspect. Now we might be willing to

accept a theory which has counter-intuitive results (such as claiming that The Brothers Karamazov can hardly be

read as art), but only if it were the only way to explain the facts of

art/aesthetic experience. This does not

seem to be the case here.

Another alleged example failing to have aesthetic attention would

be using a work of fiction to diagnose the author's neurosis. But this seems better described as a way of

being distracted from the work rather than failing to attend to it in

the right way.

Another alleged example failing to have aesthetic attention is

(mistakenly) reading a fictional work as, history. But Dickie

counters, “So?” The historical or

socially critical content, if any, of a literary work is a part of the work

(although only a part), and any attempt to say that it is somehow not a part of

the aesthetic object when other aspects of the work are, seems strange.

Therefore, Dickie maintains, there remains therefore serious doubt

that such a species of attention exists.

Alternative (more economical) explanations of alleged

Non-Disinterested Attention.

·

Ann's attention to the music turned out to be just like that of

any other listener.

·

Bob's "interested attention" to the painting turned out

to be a case of not attending.

·

Free associating and diagnosing the author's neurosis turned out

also to be cases of not attending.

·

Attending to historical or socially critical content turned out to

be simply attending to one aspect of literature.

#3

Aesthetic Perception: "Seeing As"

Virgil

Aldrich developed an aesthetic theory out of one of the central notions

of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Claims it is something that a subject does or something that

happens to the subject that determines whether an object is an aesthetic object

or not. Aldrich's view concludes that

there is an aesthetic mode of perception.

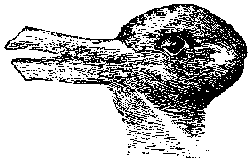

Wittgenstein called attention to ambiguous figures.

Most famous is "the

duck-rabbit":

(see: http://faculty.ccri.edu/paleclerc/existentialism/perc_figure.shtml)

Three

things can be distinguished

1. the

design the lines make on paper

2. the

representation of, say, a duck

3. the

other representation of, say, a rabbit.

Note

this phenomenon requires a more complicated model of perception then is

commonly appreciated:

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Object

(Distal

Stimulus) à |

Retinal

Image (Proximal

Stimulus) à |

Active

Mind à |

Percept

(Duck

or Rabbit, depending on #3; that's the only variable.) |

Note

that whether one sees a duck or a rabbit is the result of something the

perceiver does, consciously or unconsciously.

Three things can be distinguished in the case of such figures.

1. the design the lines make on paper

2. the perception of, say, a duck

3. the other perception of, say, a rabbit.

Aldrich claims that aesthetic

theory parallels the perceptual phenomenon of ambiguous figures. He argues that earlier theorists were

mistaken in thinking that there is only one mode of perception. There are two: the aesthetic mode of perception

and the

non-aesthetic mode of perception.

1. Non-aesthetic

("observation")

2. Aesthetic mode

("prehension")

Observation and its object ("physical object") parallel

the “seeing of, say, the duck.” Prehension

and its object ("aesthetic object") parallel the seeing of, say,

“seeing of the rabbit.” The parallel of

the ambiguous design made on the paper itself Aldrich calls a "material object."

Thus we have (paralleling the above):

1. Material Object

2. Physical Object (Observation and its subsequent perception)

3. Aesthetic Object (Prehension and its subsequent perception)

Thus a material object is seen as a physical object when observed

and as an aesthetic object when prehended.

A neat solution to the problem of aesthetic object.

1.

It avoids any commitment to disinterested attention or psychical

distance, which were seen to involve difficulties.

2.

It purports to be a development out of one of the most powerful

and influential philosophical movements of the twentieth century, the philosophy

of Wittgenstein.

True?

Is there any good evidence for his contention that there really

are two modes of perception? (There doesn’t seems to be.) The fact that a single design can function

alternatively as two representations gives no evidence for two modes of

perception. For example, the seeing of

the duck representation is exactly like the seeing of the rabbit representation

so far as “the seeing: is concerned.

The notion of “seeing as” may be useful

in providing an analysis of the concept of representation (interpretations),

but that is clearly another matter.

The only evidence that Aldrich gives is this alleged example:

a dark city and a pale western sky

at dusk, meeting at the sky line.

The sky is closer to the viewer

than are the dark areas of buildings.

This is the disposition of these

material things in aesthetic space.

The fact, however, that things look different and that visual

relations appear to alter under varying conditions of lighting is no reason for

thinking that there are two modes of perceiving that a person can switch off or

on. Aldrich writes that aesthetic perception "is, if you like, an

'impressionistic' way of looking, but still a mode of perception."

But, Dickie counters:

1.

Does it makes sense to speak of an “impressionistic way of

looking?”

2.

It is not the case that all the experiences we call aesthetic are

impressionistic, although perhaps some are. (What is impressionistic about

watching Hamlet?)

Another example: Watching illuminated snowflakes falling at night.

·

Does not serve as evidence for the theory that there are two ways

of perceiving.

·

Aldrich has given us no reasonable evidence for the truth of his

theory.

Aesthetic-attitude theories grew out of such nineteenth-century

theories with roots in

the eighteenth-century notion of disinterestedness and the view

that a psychological analysis aesthetic experience is the key to a correct

theory. But they reject the

eighteenth-century assumption that some particular feature of the world such as

uniformity in variety triggers the aesthetic, or taste, response. Instead, the aesthetic-attitude theories

share with the nineteenth-century aesthetic theories the view that any object

(with certain reservations about the obscene and the disgusting) can become an

object of aesthetic appreciation. Still,

they reject the nineteenth-century assumption that aesthetic theory must be

embedded in a comprehensive metaphysical system, (e.g., Schopenhauer's

philosophical system).

Theories of aesthetic attitude have three main goals.

1.

Isolate and describe the psychological factors constituting the

“aesthetic attitude.“’

2.

Develop a conception of aesthetic object as that which is the

object of the aesthetic attitude.

3.

Account for aesthetic experience by conceiving of it as “the

experience derived from an aesthetic object.”

Aesthetic-attitude theories held that these works of art contain

elements that are not only aesthetically irrelevant, but positively destructive

to aesthetic values. But to make this

case, they must define “aesthetic properties” (those relevant to aesthetic

appreciation) in a non-question begging way.

The danger is that they seem to be defining/explaining aesthetic

experience in terms of aesthetic properties in terms of aesthetic attitude in

terms of aesthetic experience.

(Viciously circular and, as such, pseudo-explanations.)

For these theories, an aesthetic object has the function of being

the proper locus of appreciation and criticism (with criticism understood as

including description, interpretation, and evaluation). But while this seems counterintuitive and

out of step with actual practice, they offer no compensating explanatory power.

Jerome Stolnitz

et al. attempt to explain the class of experiences referred to as “aesthetic”

by a certain frame of mind: the "aesthetic attitude." Stolnitz'

definition: the aesthetic attitude is "disinterested and sympathetic

attention to and contemplation of any object of awareness whatever, for its own

sake alone." "Disinterested" means "no concern for any

ulterior purpose," "sympathetic" means "accept the object

on its own terms to appreciate it," and "contemplation" means

"perception directed toward the object in its own right where the

spectator is not concerned to analyze it or ask questions about it."

But Dickie suggests that no successful argument has been given for

believing these accounts. It is not

clear that there really is any such thing or that the target experiences cannot

be explained without positing such.

Further, Dickie suggests that the very notion of “disinterested

attention” is incoherent. Once one

considers the motivations that exist is considered,,

there is no reason for suggesting that b the attending to a thing makes no perceptual

difference. An unique way of kind of

paying attention. But there's no reason to claim this. One of the other paying

attention or not and the elements to which one is paying attention might be

directed by certain motives or others but that doesn't suggest that there is a

unique way of paying attention to the object. The idea of "disinterested

attention" is only sensible if "interested attention" can be

distinguished from “disinterested attention.”

But it cannot Dickie maintains, because in all cases, "interested

attention" is not really a special kind of attention, but

rather, perception with different motivations or intentions>> The “attention” remains the same.

Thus Dickie argues against the idea of the aesthetic attitude in

all its forms.