Theories of Art: Formalism

Autonomy and Art for Art’s Sake

Form and Content

Formalism Proper: History Of

Modernism

Clive Bell and Aesthetic Emotion

Formalism and Music

Understanding

and Appreciating Music

Abstract Art and the Value of Form

Problems

Four Puzzling Facts About “Significant Form” (whatever it is)

Several Final Objections to this View

Theories of Art: Formalism

Clive Bell, from Art

Eduard Hanslick,

from On the Beautiful in Music

Leonard B. Meyer, "On

Rehearing Music"

Malcolm Bradbury and James

McFarlane, "The Name and Nature of Modernism"

Autonomy and Art for Art’s Sake

No one has yet

been able to demonstrate that the representational as such either adds or takes

away from the merit of a picture or a statue.[1]

Clement Greenberg, Art and Culture

At a certain

point we begin to be told that there is only one thing, one thing alone, to be

looked for in art. [2]

Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth‑Century Art

It is necessary, therefore,

for me to put up a preliminary hypothesis of the existence of pure and impure

works of art....

Roger Fry, "Some Questions on Esthetics"

There is no such thing as a moral or an

immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all …The only

excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is

quite useless.

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

One of the chief goals of Formalism is to establish the

autonomy of art. That is, art is not

subservient to some social, educational or moral purpose. It is not to be utilitarian, or at least, to

judge is on those term is not to engage with it as art. Art is to

be judged as art on its own terms. But if that's true what are these terms? But

then:

·

What is art?

·

How is it to be judged?

·

Why is it valuable?

Mimetic Theory: reference

to subject matter & representation (accuracy). Thus, art is subordinate to truth

and morality.

·

Art is an autonomous realm, sufficient unto

itself.

·

Subordinate to nothing.

·

Judged by its own internal standards.

"Art for art’s sake,"

Monroe Beardsley (1915-1985) explains this slogan as

"the recognition of a work of art as an

object in its own right, intelligible and valuable as such, with intrinsic

properties, independent of its relations to other things and to its creator and

perceiver."

Autonomy = freedom

from having to conform to external rules or community standards.

Hegel claimed that “Freedom craves to be absolute.”

Formalism contends that “Artistic Value” and

significance is independent of representational qualities, moral values, (and perhaps

even any pleasure an audience derives from the work).

As William Gass claims, "goodness knows nothing of

beauty."

The 20th Century Formalist Roger Fry claimed

that

"All art depends upon cutting off the

practical responses to sensations of ordinary life, thereby setting free a pure

and, as it were, disembodied functioning of the spirit."

Formalism can be seen as a development out of one of

eighteenth‑century aesthetic theories. For instance, in The Critique of Judgment (1790),

Immanuel Kant asserts that aesthetic judgments, represented paradigmatically by

judgments of beauty, are logically independent of judgments of morality,

utility, and truth. For Kant, the pure

aesthetic judgment is one which he calls "non-conceptual," by which

he means that it is not made by

reference to any concepts of what the object being judged ought to be like. The

Aesthetic Response is an impersonal response.

Thus formalists like Fry claim that art is an "expression of the

imaginative life" with the absence of responsive action.

·

No moral responsibility

·

Life freed from the necessities of actual

existence.

This theory of art grants to art a near absolute freedom and autonomy

Two aspects to the idea that art is autonomous.

1.

Free from external considerations (relation

to things outside)

2.

Artworks must have an internal subject

matter that is sufficient unto itself (leads to the concept of “form”- the “perceptually

given”).

Form and Content

Form (Look

over notes on Elements and Principles of Visual Art

1.

Elements of Form: What individual members of

a given class of objects have in common.

(Platonic Universal) Formal properties of art must be universal

properties.

2.

Principles of Form: These are repeatable

principles which organize the elements of artworks, where, while each work has

its own unique form, it can share formal properties with other artworks (i.e.

iambic pentameter, visual symmetry, musical key or time signature).

Two ways of understanding "Form"

1.

In contrast to content. (The story of

Oedipus as the “content” but note that this same content can be presented in different

art forms (e.g. of a tragedy, a ballet, a movie).

But... it is difficult to maintain that content is independent of

form. The formal differences between

poetry and prose seem to change the kind of message (content) it can convey. One thinks for instance of the slogan. “The

medium is the Message.”[3]

Note the E. E. Cumming’s poem:

"anyone lived in a pretty how town":

anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn't he danced his did

2.

The organization of the "elements" of a work.

Note: Key to critical appreciation of a work of Art will be

determining what precisely are the Formal Elements and Formal

Principles of that work/medium. See Elements and Principles of Visual Art

Beardsley:

A formal description and this formal

critical examination of an object of art with in volve

1.

“Element Statements:” "those statements

that describe the local qualities of elements, and the regional qualities of

complexes, within a visual design or a musical composition,

2.

“Principle Statements” “those statements

that describe internal relations among the elements and among the complexes

within the object. These latter statements we may call ‘form‑statements’.

Elements and Principles of Art

http://www.slideshare.net/kpikuet/elements-and-principles-of-art-presentation?related=1

Formal Analysis of

Da Vinci’s “Last Supper”

http://www.slideshare.net/nichsara/formal-analysis-tutorial-2-d

“Everything Set to Medium”

http://stapletonkearns.blogspot.com/2009_07_01_archive.html

Form is any

relation between elements that figures in our appreciation of the work.

But... what level of analysis is correct to look for with

respect to the distinction between form and the elements (or constituents) of

the work? Formal properties can occur at

various levels as well. (Sound and visual aspect of poetry, complex aspect of

meanings.)

·

The relations of the sounds

·

The visual structure of the words on the

page

·

Patterns and structures of meaning,

considering not only the relation of words to each other but also relations

among larger structures, such as verses and stanzas.

Beardsley: "the point of view he chooses, or the

manner of transition from scene to scene, or the proportion of description to

dialogue."

Broad definition of form:

Understand (wrt literature,

plays, films, etc.) "form" in the arts as the contrast to the matter

or elements that the work organizes. This definition of form applies to every

type of artwork and probably best captures what formalism is all about.

Develops as a stand-alone theory of art in the early

twentieth century.

·

However, proper form had been a prominent

concern since the days of Ancient Greece.

·

Plato and Aristotle each talked about the

importance of from with respect to beauty (Harmony and “Organic Unity”)

·

Pythagoras had demonstrated the musical

harmonies correspond to geometric proportions:

1:2 (octave), 2:3 (harmonic fifth), and 3:4 (harmonic fourth).

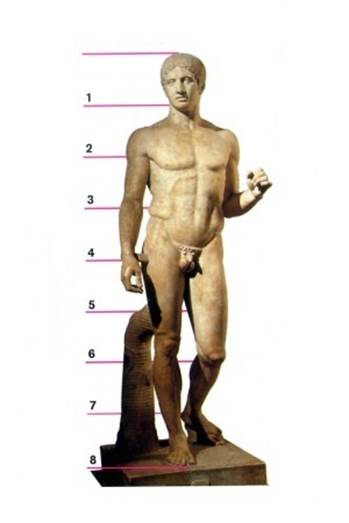

EX: Polykleitos (5th century BC) ' "Kanon"

This ancient Greek sculptor of great renown dictated

that a statue should be composed of clearly definable parts related to one

another through a system of ideal mathematical proportions.

Doryphoros (Canon)After Polykleitos of Argos (Greek, ca.

480/475–415 BCE)

http://www.learner.org/courses/globalart/work/138/index.html

|

|

|

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zojMBDSiNIU

Nevertheless, historically formal proportionality and

elements of “design” were regarded as subservient to mimetic goals of the work and

to the beauty of what is represented. In

contrast we are now being asked to attend to the purely formal beauty, or

beauty of form even if it has no representational goals. (EX: Baroque music). Denis Arnold remarks "these abstract

works of Bach's old age [such as the Art of Fugue] have puzzled musicians and

scholars." "Abstract

Works" were puzzling because they neither had a representational function

nor expressive. Before the early 20th

Century, no doctrine of the arts had been put forth which locates the very

nature and meaning of artworks in form. Formalism authorized artists to create

purely formal, nonrepresentational artworks (first in music, then in visual

arts and literature) whose sole value was to be derived in the aesthetic

contemplation of the formal arrangement of their elements.

On this view, a landscape was merely an “excuse” to

consider pure formal beauty.

Two

Formalist Theories:

1. Formalism

(proper)

2. Media

Formalism (we’ll deal with this

later)

We must distinguish between tow related ideas: "Formalism"

and “Modernism." The distinction is

blurry but essentially, "Formalism"

refers to a theory of art which could/should be applied to all works of art

irrespective of the actual historical situatedness of the work. It does not refer to a (historical) trend in

recent art. "Modernism," by contrast, is a vague, and unfortunately an

ambiguous term. We use the term to

locate historically a distinct stylistic, a phase of art history which is

ceasing or has ceased or sometimes to sum up a permanent modernizing state of

affairs.

Richard Hertz regards historical art movement of modernism

as the valuing of the "ahistorical, scientific, self‑referential,

reductionistic" and as being committed to "exclusivity, purity and

removal from societal and cultural concerns" from art.

Alternatively, others have suggested that Modernism

is/was

"the movement towards sophistication and mannerism, towards

introversion, technical display, internal self‑scepticism,

has often been taken as a common base for a definition of Modernism."

Note: "Post‑

modernism" is at least as obscure as "modernism" is obscure.

Basic distinction between Modernism and Formalism is

that Modernism (like Abstract Expressionism) is a historical movement, whereas

Formalism, is a philosophy of art in general.

The latter is a theory of art which is thought to apply to all art,

including art of the past.

Formalism

Proper

In his 1914 book Art[4],

Clive Bell proposed we understand Art as “Significant Form”

Bell argues that all art must have something in common.

For either all works of visual art have some

common quality, or when we speak of “works of art” we gibber. Everyone speaks

of “art,” making a mental classification by which he distinguishes the class

“works of art” from all other classes. What is the justification of this

classification? What is the quality common and peculiar to all members of this

class? Whatever it be, no doubt it is often found in company with other

qualities; but they are adventitious — it is essential. There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist;

possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless.[5]

Thus the hunt it on for that which all and only Works of

Art have in common, in virtue of which they are Works of Art. Classification is only justified if there is some essential quality that all artworks

share that we refer to when we use the term "art."

For the Formalist, formal relations are not merely

considered important in an artwork, but rather the formal properties of a work

are primary, and other concerns are secondary, wholly irrelevant or even a detraction.

"The starting point for all systems of aesthetics must be the

personal experience of a peculiar emotion. The objects that provoke this

emotion we call works of art."

Bell draws a distinction between two types of emotions

elicited by artworks:

·

"Aesthetic Emotion"

·

"Emotions of life"

"A painter too feeble to

create forms that provoke more than a little aesthetic emotion will try to eke

that little out by suggesting the emotions of life. To evoke the emotions of

life he must use representation. Thus a man will paint an execution, and

fearing to miss with his first barrel of significant form, will try to hit with

his second by raising an emotion of fear or pity."

"A good work of visual art carries a

person who is capable of appreciating it out of life into ecstasy: to use art

as a means to the emotions of life is to use a telescope of reading the news."

"We are all familiar with pictures that

interest us and excite our admiration, but do not move us as works of art. To

this class belongs what I call 'Descriptive

Painting' that is, painting in which forms are used not as objects of

emotion, but as a means suggesting emotion or conveying information."

With respect to music Bell claims that he does at times

"appreciate music as pure musical form,

as sounds combined according to the laws of a mysterious necessity, as pure art

with a tremendous significance of its own and no relation whatever to the significance

of life.”

It is this aesthetic emotion toward the object and thus

causes us to label it "art."

What is it that provokes the unique aesthetic

emotion? Only the formal properties

could do the trick.

What Bell calls “Significant Form.”

“Formal properties and nothing else are what makes

artifacts of the past art.”

Argues that what he calls "significant form" is the defining

quality of art .

·

Each artwork provokes its own particular

emotion, but each particular emotion is of this special type.

·

Bell claims that it is just this common

quality which causes the aesthetic emotion by which we know and experience

objects as works of art.

What is this "Something?" -- "Significant Form"

Bell regards his proposal as an empirical hypothesis based on, and intended to account for,

observations (our collective experience of artworks). Not unlike the 18th and 19th

century aestheticians, he is claiming that there is a unique set of experiences

and that these can only be explained by an appeal to objective formal

properties.

I shall not, however, be under the delusion

that I am rounding off my theory of aesthetics. For a discussion of aesthetics,

it need be agreed only that forms arranged and combined according to certain

unknown and mysterious laws do move us in a particular way, and that it is the

business of an artist so to combine and arrange them that they shall move us.

These moving combinations and arrangements I have called, for the sake of

convenience and for a reason that will appear later, “Significant Form.”

This peculiar emotion cannot be explained by

“Association of Ideas” theories because

1. The Aesthetic Emotion is not among the “Emotions of

Life”

Not everyone can feel this emotion, at least fully. And it cannot be explained.

“… It means that his aesthetic emotions are

weak or, at any rate, imperfect. Before a work of art people who feel little or

no emotion for pure form find themselves at a loss. They are deaf men at a

concert. They know that they are in the presence of something great, but they

lack the power of apprehending it. They know that they ought to feel for it a

tremendous emotion, but it happens that the particular kind of emotion it can

raise is one that they can feel hardly or not at all.”

2. Emotional associations cannot explain the enduring

admiration we pay to great works of art across the centuries.

Emotional associations are dependent on specific

cultural contexts, as well as the specific meanings of subject matter, and thus

will be lost on observers from other times and cultures. They cannot explain the enduring admiration

great works of art receive. Indeed, Bell

suggests, in a manner similar to Hutchinson, that the association of ideas can

in fact distract us from what it of real significance in an artwork. For Bell, it is better that observers not

understand artworks; this makes their responses purer.

“Let no one imagine that representation is

bad in itself; a realistic form may be as significant, in its place as part of

the design, as an abstract. But if a representative form has value, it is as

form, not as representation. The representative element in a work of art may or

may not be harmful; always it is irrelevant. For, to appreciate a work of art

we need bring with us nothing from life, no knowledge of its ideas and affairs,

no familiarity with its emotions. Art transports us from the world of man’s

activity to a world of aesthetic exaltation. For a moment we are shut off from

human interests; our anticipations and memories are arrested; we are lifted

above the stream of life.”

3. Only Formal Properties can explain why we are moved

aesthetically.

Thus Bell Formalism is, allegedly, able to explain

otherwise unexplainable facts (great art's appeal to viewers of widely

divergent cultures and times). It is

form to which viewers are responding. (Seems initially plausible).

1. What is meant by "Significant Form?"

·

Are we to contrast this with “insignificant”

formF.

·

Which formal relations among which formal

elements are "significant," and why?

Bell's unhelpful answer: Something is significant form

if and only if it provokes aesthetic emotion.

·

Significant form is supposed to explain what

provokes our aesthetic emotions, but it is defined in terms of aesthetic

emotion. (Significant Form it that which causes that which only significant

form can cause.)

·

Subjectively fixing the causes prevents him

from given any objective characterization of which combinations of elements these are.

·

Could the stronger claim also be true; that

significant form is nothing but such color arrangements in all pictures?

(Connected to Bell's claim that we need apply no knowledge except that of three‑dimensional

space).

2. Is it true that "to appreciate a work of art we

need bring with us nothing but a sense of form and color and a knowledge of

three‑dimensional space? “

Roger Fry claims that attempting to explain the concept

of significant form adequately would take one to "the depths of

mysticism."

Formalism, Objectivity and Music

Formalism in music argues against the customary emphasis

in music on emotions.

Eduard Hanslick 1825-1904),

the most influential formalist theorist of music, insists that his theory of

music derives from a purely objective approach. His argument depends on the

conceptual connections between autonomy, objectivity, and form. Hanslick’s 1854 work On the Musically Beautiful argues

for a Formalist conception of aesthetic merit in music not unlike Bell’s.

http://www.cengage.com/music/book_content/049557273X_wrightSimms/assets/ITOW/7273X_58_ITOW.pdf

Hanslick rejects two ideas:

a. that the point of music, its meaning, is

ultimately to be understood in terms of emotional effects.

b. that the meaning of music is to be

understood in terms of its alleged ability to represent emotional states.

He attempts to develop an objective musical aesthetics

that deals with music in its own terms, that is, as an autonomous phenomenon.

Emotional responses to music come and go. (e.g. Stravinsky's

Rite of Spring) Our emotional

estimate of a piece of music varies too much, from context to context and

person to person, to be a valid basis for detecting and analyzing what is

beautiful in music. Thus he agrees with

Bell and other formalists that aspects to music do not possess sufficient attributes

of “inevitable-ness, exclusive‑ness and uniformity...” Pure instrumental music, commonly called

"absolute music" in music theory, is championed by Hanslick and other nineteenth‑ and twentieth‑century

theorists as the highest form of music.

"In the pure act of

listening we enjoy the music alone and do not think of importing into it any

extraneous matter. But the tendency to allow our feelings to be aroused implies

something extraneous to the music.” (not in whatever emotions or associations

we may connect to the music.)

Hanslick thinks the imagination (an active organ of the mind) performs

the function of constructing experience to enable us to mentally grasp external

perceptual objects. To hear sounds as music is not to feel emotions or to

think of distant scenes, but to hear the sounds with our imagination, which can

represent the sounds as pure music. We contemplates

it with intelligence. So here he distinguishes

direct effect on imagination from indirect effect on emotions.

The only valid analysis of the beauty of music must

focus on the music itself, on what is in the music, not on the music's variable

and indirect effects. Like Bell and

other Formalists, Hanslick's argument thus shows that

a demand for complete autonomy for artworks (and I would argue coupled with a

demand for objectivity, necessity and universality) implies a rejection of

mimetic theories and expression theories of art in favor of the formal

'relation of elements within the artwork.

What remains after we put aside the emotional and

representational content is the musical content, the musical properties of sounds.

“The primordial element of music is euphony,

and rhythm is its soul. . . . The crude material which the composer has to

fashion ... is the entire scale of musical notes and their inherent

adaptability to an endless variety of melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. Melody

... is preeminently the source of musical beauty."

Note:

not only is he identifying the elements of music so as better to discern

musical formal properties, but also tacitly recommending a research project for

each artistic medium, i.e. to discover its own essential nature (Minimalism-

media formalism)

An “intellectual principle” implied, Hanslick

argues since it "as essential, for we would not apply the term

"beautiful" to anything wanting in intellectual beauty; and in

tracing the essential nature of beauty to a morphological source, we wish it to

be understood that the intellectual element is most intimately connected with

the sonorific forms, (Note the Pythagorean Theory of Beauty is here

quite explicit.)

beauty, is a temporal phenomenon

Two Formal

Concepts of Understanding and Appreciating Music

"On

Rehearing Music," Leonard Meyer distinguishes two different

formal concepts as to what it means to “Understand and Appreciate” music:

1. The

Non-temporal Approach: a musical event "must be complete, or virtually

so, before its formal design can be comprehended";

Such thinkers maintain that music is to be contemplated

as a completed whole structure.

2. The

Kinetic‑syntactic Approach: music "is a dynamic process.

(Understanding and enjoyment depend upon the perception of and response to

attributes such as tension and repose.... music is seen as a developing

process")

The primary example of music to be experienced in this

way is Western music from 1600‑1900, which is characterized by a kind of

harmonic development that requires modulation between keys and resolution of

harmonic tensions. This harmonic development, in conjunction with manipulation

of thematic material, gives such music a prospective and dramatic air, as Meyer

notes, a sense that the music is “always progressing forward.”

Kinetic position:

"The

significance of a musical event be it a tone, a motive, a phrase, or a section

lies in the fact that it leads a practiced listener to expect, consciously or

unconsciously, the arrival of a subsequent event or one of a number of

alternative subsequent events."

The degree of the probability of subsequent

events contributes to the sense of significance or meaning we feel when

the actual musical events happen. If a piece of music is very predictable (for

example, "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star"), it has little meaning; if,

however, our expectations are much more complex and the fulfillment is much

less probable (as in a Beethoven symphony), then the music has much more

significance, because the musical notes are surprising.

This analysis of music is clearly formalist. For Meyer, meaning

depends on syntactic or structural complexity, which in turn is

connected to enjoyment. He seems to understand this enjoyment as a

psychological process to be explained some day by a more advanced cognitive

science.

For Meyer value is the enjoyment it gives us.

Hanslick grounds his account on the more traditional concepts of

beauty as well as what pleases us. Hints

that form furnishes music with even more profound values.

Abstract Art and the Value of Form

Two Chief Formalist Points:

·

negative: formalists

claim that art is not about what it might appear to be about rather, it is

about form.

·

positive: form is to

be understood so that form is important for given reasons.

What is form?

What is the value of form?

What is the value of art if formalist theories of art

are correct?

Calls for a positive account of form and its value.

Not widely accepted account of the positive value of

form, and this is one of the weaknesses of formalism as a philosophy of art.

Further... Why do we value Significant Form?

A formalist would claim that

abstract images are merely purified versions of the formal values found in

representational art.

Clive Bell is sure that form is

the thrilling aspect of art and what makes something truly art. But he is less sure just why form is

important, less sure what the meaning of form is. He does not wish to base formalism on any

foundation as shallow as mere pleasure or enjoyment.

His metaphysical hypothesis: the

ecstasy explained in terms of

a. the communication of emotion between artist and viewer.;

viewers are moved not because the work is beautiful, but because they feel the

emotion that the artist feels.

b. The emotion that the artist feels is for the pure form of

reality.

c. the emotion is for things seen not as means but “ends in

themselves.”

Bell suggests that the significance of the work of art

is that it is inspired by the artist’s a vision of "Reality." We are moved by certain combinations of lines

and colors because the artist has used these to express an emotion felt for

ultimate reality, things in themselves, divorced from all associations. Cezanne, he claimed, discovered how to paint the

essence of things, exemplifying Bell's metaphysical/epistemological

hypothesis about the value of

form.

But this explanation seems to require that we look at

Cezanne's landscapes as about landscape, not just lines and patches of

color. To create a painting that captures

the essential form of something would seem to be quite a deep artistic

achievement, and this would explain the felt "significance" of the

forms, but is inconsistent with Bell's more radical claim that

"significant form" can be entirely separated from what the artwork

represents.

Problem: Bell cannot generalize the explanation that he gives in Cezanne's

case (that Cezanne portrays the essence of a landscape for forms that do not

derive from observation).

Hanslick,

too, is eager to link the beautiful in music with themes more profound than

pleasure (communication of emotion between artist and audience), with our

realization that the sounds which stimulate our imaginations are produced by

the composer's imagination.

The difference between a

kaleidoscope and music, he claims, is

"that

the musical kaleidoscope is the direct product of a creative mind, whereas the

optic one is but a cleverly constructed mechanical toy"

Note: This distinction is very much in jeopardy give “music writing

programs.”

Note as well: A

it is a clever mind that stands behind the any clever toy.

One wonders what he would say about AI generated music or art in general.

In Hanslick's

view, the composer is inspired by the structures of musical reality and the free

play of the imagination. He is

saying both that absolute music has value and also that listening to music in

this special way, that is, contemplating it, is valuable. When these two, the

proper object and the proper way of listening, come together, the result is a

refined form of experience and an exercise of our highest imaginative and

intellectual faculties.

Four puzzling facts about significant form (whatever it is):

1. SF is both the identity criterion for art

and the evaluative criterion for art.

Therefore, some art‑like artifacts lack significant form, even

though they surely have many formal properties.

But for Bell there could never be Bad art; only genuine art (w/ SF) and

non-art (w/o SF)

2. We would normally maintain that some

genuine artworks are better than others (as works of art). But for Bell, having SF does not admit of

degrees; therefore all genuine art is equal in value.

3. Bell, at places, seems to allow that

natural object can provoke “aesthetic emotion” and, if so, must possess

significant form. But either that means

that the creation of SF can be accidental, or it means that some mind is

responsible for the SF to be found in nature (or perhaps we cannot actually

have an aesthetic emotion response to natural objects. All of these options seem problematic.

4. To appreciate a work's significant form

we do not need any knowledge of what the work represents according to Bell. He

wants to contrast formal appreciation of works of art with awareness of their

representational content. However, some

formal qualities cannot be accessed until one knows the representational

content. (i.e. would not even be able to

pick out the special relations of the objects being depicted if we did not know

what

was being represented.

It seems absurd to say the aesthetic power

of the painting is due exclusively to non-representational elements. Part of the effect simulated

distance in a picture might be explained colors and perspective. But another

reason why we might focus the spatial quality could be the nature of the events

and the significance of what is being depicted.

1. Sometimes at least, the visual relations that seem

significant gain their significance because of the viewer's understanding the

things being represented.

2. Without knowledge of the things represented, the view

cannot perceive certain visual relations.

Greatest strength: universal applicability

to both abstract and expressive art, to contemporary as well as ancient art,

and to every culture of art, which, at least in the case of music, seem in part

supported by Cognitive Science.

Great weakness: perhaps

the most esoteric account of the value of art.

Crucial question: Why do we

demand/expect our visual art be representational, but not our music?

Francis Picabia “The laws

appreciating Non-representational visual art have as yet been hardly

formulated, but they will become gradually more defined.”

Facilitated an easy formalist reading of abstract art,

but not everyone is happy with Formalism, even as an account of Abstract Visual

Art:

e.g. Maurice Tuchman:

Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1986 organized

"The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890‑1985.

“Abstract art remains misunderstood never an outright dismissal of

meaning draws upon deeper levels of meaning genesis and development of abstract

art were inextricably tied to spiritual ideas to express spiritual, Utopian, or

metaphysical ideas that cannot be expressed in traditional pictorial terms.”

This suggests that Tuchman holds something like a

mimetic theory of visual art that abstract art has meaning if and only if it

represents some ideas. Further she seems

to be implying that the major difference between traditional representational

art and abstract art would involve the subject matter.

·

Traditional art: natural world

·

Abstract art: spiritual world (abstract art

lacking such esoteric subject matter would be meaningless).

Tuchman criticizes formalist interpretations of the

history of abstract art; "aesthetic interpretations" have made the

art meaningless.

What is important in painting, for Georgia O'Keeffe, is

not representation per se but getting at the emotional essence of form:

"I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I

was looking at, not copy it."

Modrian:

"Hence as matter becomes redundant, the representation of

matter becomes redundant. We arrive at the representation of other things such

as the laws which hold matter together. These are the great generalities, which

do not change."

Newman rejected what he called the

objective approach to painting:

"The present feeling seems to be that the artist is concerned

with form, color and spatial arrangement. This objective approach to art

reduces it to a kind of ornament."

Instead, Newman held that the

painter was concerned

"with the penetration into the world mystery. His imagination

is therefore attempting to dig into metaphysical secrets....”

Donald Kuspit

notes:

"For Reinhardt the square, cruciform, unified absolutely

clean mandala shape he utilized in his famous 'black,' or negative paintings

serves the same purpose as Rothko's 'disembodied chromatic sensations,' namely

to preserve the spiritual atmosphere."

Reinhardt "a long tradition

of negative theology in which the essence of religion, and in my case the

essence of art, is protected ... from being pinned down or vulgarized or

exploited."

Bruce Nauman's Window or Wall Sign (1967), which says

in neon words: "The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic

truths.” The lack of visual illusion, the use of light as a medium, the use of

geometric form (the spiral recalling Duchamp's fascination with spirals in his

art), the self‑referential nature of its message, all work to give this

piece a mysterious sense of exemplifying

what it asserts.

It is now widely acknowledged that Cubist works do

have content, that they are about something.

However, Formalists might counter that this position

falls into the old idea that an artwork has meaning if and only if it has

content.

Several Final Objections to this View:

a. If we were to maintain this position, we

would have to say that abstract artists who reject spiritualism produce

paintings that are literally meaningless and have no content. Why say this

about paintings, but not about instrumental music?

b. Tuchman's position also places a

disproportionate weight on artists' intentions and even on their amateur interests,

for example, theosophy and so‑called sacred geometry. ("This is

guilty of the “intentional fallacy" i.e. ascribing an interpretation to a work based on properties

of the artist.)

c. No one has ever proposed that there are

no ideas behind abstract artworks and that such artworks are literally without

meaning and point. Formalists insist that the meaning or content is contained

within the formal properties, or at any rate that the viewer can understand the

meaning of the work without attributing referents to the images in the work.

d. Two obvious traditional answers to the

question of what meaning abstract works have.

i. attribution of beauty

ii. expressions of emotional states and

attitudes