DANCE OF DEATH (DANSE MACABRE OR TOTEN TANZ)

http://resources.library.yale.edu/online/TheDanceOfDeath.pdf

http://german.about.com/library/bltotentanz.htm

Macabre:

- having

death as a subject : comprising or including a personalized representation

of death

- dwelling

on the gruesome

- tending

to produce horror in a beholder

Origin of MACABRE

French, from danse macabre

/ dance of death, from Middle French (danse de) Macabré

Dance of Death

Danse Macabre (French)

Danza de la Muerte (Spanish)

Dansa de la Mort (Catalan)

Danza Macabra (Italian)

Dança da Morte (Portuguese)

Totentanz (German)

Dodendans (Dutch),

This is a folk-drama dance that originated in

Medieval Europe. The subject of this

traditional performance is the human condition, and in particular the end of

human life. While it existed as the most

ephemeral art-form, Dance, we see it also displayed through paintings and

poetry. It precise origin is unknown, however verse

dialogues between Death and each of his victims, came into existence shortly

after the Black Death in Germany. These

could have been performed as plays and as we have seen these initial proto-dramas

might have morphed into a more substantial folk-drama dance.

We know that the term "danse

macabre" was known and used before 1424 (i.e. even before the creation of

the earliest known wall mural of the Dance Macabre in Cimetière

des Innocents in Paris. In his poem entitled Respit

de la Mort, Jean Lefevre writes:

Je fis de Macabre la danse,

Qui tout gent maine à sa

trace

E a la fosse les

adresse.

Some have suggested that that the poet had

himself just escaped the Black Plague when he wrote this.

The Evolution of Western Conceptualizations of Death

It is worth considering how the skull and

skeleton became emblems of death, and gruesome ones at that. It was not always so. During the early Christian centuries, before

this religion came to dominate the Western mindset, the vision of “life/death”

prevalent was one of a “carpe diem”

philosophy where one is considered well advised to enjoy pleasures of the

moment without too much concern for the future.

Worrying about death only cut into the time one could enjoy life and so it

was relatively unproductive. Epicureans

adopted the earlier Greek philosopher Democritus’s view that the soul, whatever

else it might be, was a physical collection of atoms that is dispersed at the

death of the body. We need not fear

death since “we” won’t be around to experience anything, good or bad. Epicurus and other classical thinkers had

taught that “Death is nothing to us, for when death is we are not and when we

are, death is not.” (For teaching that

there is no afterlife Dante claimed they were confined to living graves in

sixth circle of hell in his Inferno.) And while the Stoics taught that we each have

a soul that will survive the death of the body, one should not presume this

afterlife would include any of the pleasures (or pains) of the body. We will not actually take pleasure in this

existence. Further, some suggests a loss

of our individuality, a ‘cosmic recycling’ so to speak where we each mingling

into the whole.

In antiquity, portrayals of death were generally

benign. The Classical tradition

continued into the early Christian Era. In most ancient Christian art, death is

represented as the youth with the inverted torch carved on sarcophagi, but the

custom died out. Death was represented

as the brother of Sleep, “approaching mortals gently, but with swift pinions

(bird like feathers).” (Thanatos/ Mors

twin brother of Hypnos/ Somnus). In classical times the skeleton seen mostly as

a comic figure. Even in the early Middle Ages, the skeleton is never found as a symbol of

death. It does not appear to have that

significance until the beginning of the 15th century.

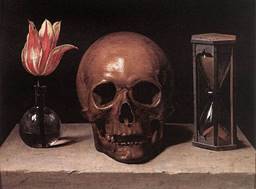

Memento Mori

By the Late Medieval Period the attitude towards

death was entirely different. The

terrifying aspect was no longer softened or avoided, but deliberately

emphasized. There developed a pronounced

“MEMENTO MORI” philosophy: remember that you must die, a reminder of

mortality. The phase has originated in

the Roman Empire, but at that time is was a reminder to “gather ye rosebuds

while ye may.” During the Middle Ages, far from a warning to take advantage of the

pleasures the world has to offer us while we can, it became a warring to repent

and resist temptations. During this time

the skeleton and skull become awe-inspiring and/or repellent. They were symbols that even the illiterate

masses could understand. Death is the

inevitable leveler of us all. The most

drastic means were used during this time to emphasis to the public the sense of

the impermanence of the physical body and of all earthly things, in order to

point a moral lesson: The body was not going to live forever; it was going to

die.

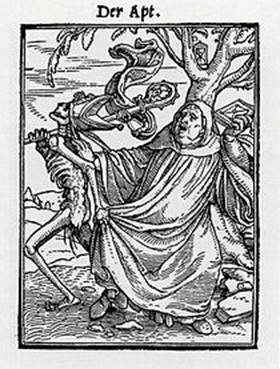

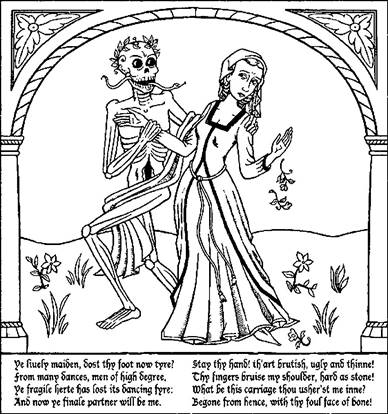

It precise origin is unknown, however verse

dialogues between Death and each of his victims, came into existence shortly

after the Black Death in Germany. These could have been performed as plays and,

as we have seen, these initial proto-dramas might well have morphed into a more

substantial folk-drama dance. The festival/dance began a as a sort of parade or

farandole. A dancer dressed, as a skeleton,

represents “Death.” He begins his dance

and then selects someone standing on the sidelines and anyone he selects is

compelled to dance with him. This street

festival type dance eventually became choreographed and stylized so those selected

were actually dramatic representations of individuals or ranks in society. In its developed form, the first chosen came

to be one dressed as the Pope (signified by his triple crown). Death would then select an emperor (signified

by his sword and globe) and so on gathering members from all levels of society:

(the usurer with his large purse) and the poor man (soliciting a loan). All succumb to Death. And this dramatic dance/drama is clear enough

for an illiterate person to understand them.

It also had the unsetting effect of mixing (in drama) the dead and the

living, the movement of life and the stillness of death. This is remarkable when one considered that

funerals are among the very few traditional ceremonies where there is no

dancing.

The dance/dramatic form proceeded to visual

representations in paintings, engravings and frescos. The selection of the skeleton as dancing

death arose out of superstitions about the dead returning and being malevolent

or foreboding. Unlike many other cultures

were the dead are regarded as a source of protection and power, there developed

a great fear of the dead, and dead bodies.

This may have resulted from the plagues rampant in

In the 15th century, the commonest form of the

Dance of Death representation was mural painting. Very few remain. The Middle Ages were

regarded as the age of darkness and barbarism by the time of the Renaissance

onward, so wall paintings of that period were thought of little importance and

often painted over and/or otherwise destroyed.

In the parts of

The first poem represented living dancing with

the dead is Jean Le Fevre’s “The Dance of Death”

1374 –a poem he wrote after experiencing and surviving the Plague. Scholars theorize that the tradition

originated in France, but representations of the Danse

Macabre can be found in

Emperor, your

sword won’t help you out

Sceptre and crown are worthless here

I’ve taken you

by the hand

For you must

come to my dance

Something of the Memento Mori can be see today in the Mexican festival Day of the

Dead, including the images of skull, skeletons and bones representing death and

the dead.

Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada has

created various works in which various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.