The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Thomas Kuhn and The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions

Six Distinct Stages With Respect

to Scientific Progress

1.

Prescience

3.

Model Drift

4.

Model Crisis

C: No neutral criteria for theory choice

________________________________________

The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions

Many early philosophers of science had suggested that scientists

are in the business of confirming their theories. That is that they begin with

a theory and then they look for evidence which proves that this theory is true

and offers epistemic warrant confirmation. So, I begin with a certain

hypothesis which predicts experimental results are I performed the experiment

and I get experimental results are and thus I have confirmed my initial

hypothesis. While this view of what is

going on in science might have initial appeal, it actually is

deeply flawed according to Karl Popper.

Karl Popper (1902-94) set some

very high standards for scientific rigor.

He suggested by contrast, that scientists are (should be) constantly to

setting out to disprove their work. Any

current scientific theory, for Popper, is always in the state of being “not yet

disproved.” There is something to be

said for this approach of looking for data to contradict one’s beliefs rather

than more data that supports them.

Instead of seeking to confirm what a theory claims to be the case,

Popper is using potential conflict between a theory, its predictions

and actual data about the real world to drive science forward.

Popper points out that we cannot really verify a theory if

theoretical testing amount to:

Theory T predicts observation O.

O occurs.

Therefore

Theory T it true.

This simply amounts to:

If T then

O

O

Therefore

T

But this is the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Nothing (strictly) follows from the premise

set [(P -> Q) & Q]. Thus,

according to Popper, theories cannot be conclusively confirmed, rather they can

only be falsified. Science progresses according

to Popper not by Confirmation, but by repeated attempts at falsification.

Testing must take the form Theory T predicts observation O. If O occurs it tells

us next to nothing. However, if O does

NOT occur (~O), we have falsifying evidence for Theory T.:

If T the O

~O

Therefore

~T

This, by contrast, is not a fallacy at all. Rather it is the logical deductively valid

syllogism known as modus tollens. But

this means theories can only be falsified, NOT verified.

Now, the longer a theory resists falsification the more credence

it gains, but it never is verified in the absolute sense. This is why, Popper maintains, that every

current scientific theory is in the state of being “not yet disproved.”

Popper argues that science is accountable to rigorous, objective

standards, in particular falsification, which he regarded as the core of

science. This is how science progresses according to Popper, but further, this

is what demarcates genuine science from pseudo-science. Falsifiability is the hallmark of true

science. Any “theory” that cannot be

falsified is at best pseudo-science (e.g. Marxism[1]). But later philosophers were critical a Popper’s view.

This, they claim, is idealized science at best. It is not how actual science is

practiced. When Thomas Kuhn looked at

the history of science, he couldn’t find

much evidence of this falsification process actually

happening in practice. Thus is could NOT be an accurate account of how science

progresses.

Thomas Khun and The Structure of

Scientific Revolutions

Thomas Kuhn (1922-96) developed a theory of science that directly

challenges that of Karl Popper. He

argues that most of the time science (what he called Normal Science) operated

within a set of given assumptions or a “Paradigm” that is taken as given and

not subject to testing. If Kuhn is

correct here, this would greatly restrict the extent to which Popperian

disproof could actually happen. In fact, the Paradigm as conceived by Kuhn is

a sort of fundamentalist orthodoxy about “how the world is.” Normal Science is, according to Kuhn, the

process of mere elaboration of the prevailing Paradigm or central theory in

ever more detail. A whole generation of

scientists grows up with this set of common assumptions and they exhibit strong

resistance to any data that might call the central Paradigm into question.

Originally printed as an article in the International Encyclopedia

of Unified Science

Here Kuhn argues that science does not progress via a linear

accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions, also called

"paradigm shifts." Here he

reviews past major scientific advances and attempts to show the “steady

accretion of scientific progress via normal falsification” view of scientific

progress (a la Popper) was just wrong, or, at least

incomplete. Instead, Kuhn claimed that

science advanced (and advances) the most by occasional revolutionary explosions

of new knowledge, each revolution triggered by the introduction of new ways of

thought so large and different they must be called “paradigm shift.” From Kuhn's work came the popular use of

terms like "paradigm," "paradigm shift," and "paradigm

change." These are radical reimaginings of “the way the world is.”

1.

a typical example or pattern of something; a model. "there is a new paradigm for public art in this country"

2.

a worldview underlying the theories and methodology of a

particular scientific subject.- Kuhn’s notion "the discovery of universal

gravitation became the paradigm of successful science"

3.

a set of linguistic items that form mutually exclusive choices in

particular syntactic roles. "English determiners form a paradigm: we can

say “a book” or “his book” but not “a his book.”

Thomas Kuhn defined paradigms as

"universally

recognized scientific achievements that, for a time, provide model problems and

solutions for a community of researchers,"[2]

In short, a paradigm is a comprehensive model of understanding

that provides a field's members with viewpoints and rules on how to look at the

field's problems and how to solve them.

"Paradigms gain their status

because they are more successful than their competitors in solving a few

problems that the group of practitioners has come to recognize as acute."

Kuhn challenges the traditional understanding of how science

“progresses.” He argues that the history

of science is punctuated by moments of revolutionary breakthroughs

("paradigm shifts”). During these

times, the entire scientific discipline is transformed.

Kuhn outlines six distinct stages with respect to scientific

progress:

1. Prescience: Here there is a general lack of an unifying central paradigm.

(In a given discipline the stage only occurs once. Subsequently,

there is always an existing paradigm.)

All new fields begin in Prescience, where they have begun to focus

on a problem area, but are not yet capable of solving

it or making major advances. A field

cannot make major progress on its central problems at this point because it

cannot articulate, and therefore does not know what the “major problems”

are. Without a working paradigm, it

lacks the tools necessary to conceptualize the problems to be addressed. Consequently if cannot tell what an “answer”

to the “problem” would look like.

Similarly, it cannot collect “relevant facts/ evidence” since is lack a framework necessary to distinguish “relevant”

facts from “irrelevant” facts. In this

period, one starts from ground zero and attempts to build a science from

scratch. Because there is no paradigm to

organize the data, all facts seem equally relevant. Science consists of simple indiscriminant data collection with no real organizing

principle.

2. Normal

Science: scientists operate within an overarching paradigm that guides them in

their research, the formation of questions, conducting experiments. The paradigm provides them with a means to

ask the questions and test the answers to those questions. This is a "puzzle-solving"

phase. Guided by the paradigm, normal

science is extremely productive:

"when the paradigm is successful,

the profession will have solved problems that its members could scarcely have

imagined and would never have undertaken without commitment to the

paradigm".

In this stage, scientific progress consists in extending our

knowledge of relevant facts (as delineated by the paradigm), working on those

issues highlighted as important by the paradigm, increasing the match between

the observations and the paradigm's predictions, and further development and

articulation of the paradigm. Scientists

doing “normal science” do not work to refute or overthrow a paradigm, or even

to find out whether it is true, according to Kuhn; they presuppose that it is

true, and work on that assumption.

Again, this puts Kuhn in direct opposition to Popper and the claim that

scientific progress is only had by repeated attempts at falsification.

3. Model

Drift: During this period we begin to see, in the course of

normal science, failures of experimental results to conform to the paradigm’s

predictions. However, these failures are

seen not as refuting the paradigm, but rather attributed to mistakes by the

researchers.

A few anomalies -- cases in which the observational facts do not

match up with what our paradigm has led us to expect -- can always be explained

away. (The experiment was badly performed, the beakers weren't washed well

enough, there must be another planet we haven't found yet, . . . )

This, Kuhn argues, in seeming opposition to Karl Popper's notion

that science “corrects” itself and progresses via the “falsifiability

criterion.” However, during this phase, as the anomalies accumulate, a sense

grows within the scientific community that something is fundamentally wrong.

4. Model

Crisis: As anomalous results accumulate the paradigm comes to a “crisis stage.”

As anomalies accumulate, there grows the suspicion that something

is fundamentally wrong. Again, Kuhn

argues this in seeming opposition to Karl Popper's notion that science

“corrects” itself and progresses via the “falsifiability criterion.”

5.

Model Revolution: at this point at new paradigm is formulated. The new paradigm subsumes the old set of

observations, both the anomalous results and non-anomalous results into one

coherent framework.

Even so, there is (will be) resistance within the scientific

community to adopt the new paradigm. There is an inherent conservative impulse

in science, according to Kuhn, and the “old guard” scientists will seek to

preserve their previous worldview.

6. Paradigm

Shift: at this point the new paradigm is accepted and the old one

discarded. This is termed “revolutionary

science.”

Kuhn suggest that this may take a

generation. Older researchers, trained

and accomplished in the old paradigm, may need to die off and make room for new

researchers open to the new paradigm before it can gain a foothold.

The change from one paradigm to another is not dictated by the

observational data in any straightforward way. Both paradigms will have ways of

accommodating the data, and proponents of the different paradigms may have

different interpretations of the criteria for theory choice, so that theory A

looks simpler (or more coherent with existing theory, etc.) to proponents of

theory A, while theory B looks simpler to proponents of theory B.

Moreover, to some extent proponents of differing paradigms have

difficulty even communicating with each other, because they will use the same

terms (phonemes) to mean different things

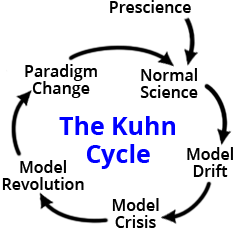

The Kuhn Cycle

The Kuhn Cycle is preceded by the Prescience step. After that the

cycle consists of the five steps:

Kuhn’s account of scientific progress has Darwinian/ evolutionary

overtones.

Punctuated equilibrium: is a theory in evolutionary biology which

proposes that most species will exhibit little net evolutionary change for most

of their geological history, remaining in an extended state called stasis. When

significant evolutionary change occurs, the theory proposes that it is

generally restricted to rare and geologically rapid events of branching

speciation....

Punctuated equilibrium is commonly contrasted against the theory

of phyletic gradualism, which states that evolution generally occurs uniformly

and by the steady and gradual transformation of whole lineages (called

anagenesis). In this view, evolution is seen as generally smooth and

continuous.

Kuhn also argues that rival paradigms are incommensurable. It is

not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and

terminology of another rival paradigm.[3]

David Stove and other critics of Kuhn, claimed that this account of science

suggests that theory choice is fundamentally irrational and relative. If rival theories cannot be directly compared

in some objective way (non-paradigmatic), then one cannot make a rational

choice as to which one is better.

Kuhn stresses a notion he calls incommensurability. We are always

in one paradigm or another and thus using a framework to interpret a rival

framework. Kuhn himself denied his view

has this result. (third

edition of SSR), and sought to clarify his views to avoid further

misinterpretation. Freeman Dyson has

quoted Kuhn as saying "I am not a

Kuhnian!" This notion of “no

neutral space” idea gets applied, in a number of

different areas with a common pattern. Here are some of them:

This is the most basic sense in which Kuhn uses the notion of

incommensurability. The idea is that different paradigms, even if they use the

same vocabulary, will use it in different ways, so that scientists committed to

the differing paradigms will tend to "talk through" each other. The

theoretical justification here seems to be that any aspect of a theory can affect the meanings of its terms -- there is no distinction

between "analytic" and "synthetic" sentences, between

sentences which merely give the meanings of terms and sentences which state

facts about the world.[4] So there is no way to give neutral

definitions of words shared by different theories, definitions both theories

can accept. And so it is extremely

difficult (Kuhn doesn't actually say

"impossible") for proponents of one paradigm to even figure out what

proponents of another are really trying to say.

(It would require them to be “bilingual.”)

Observation is "theory-laden": what we observe depends

to some extent on our theoretical commitments. Our theories provide the

categories in terms of which we classify our observations, and thus to some

extent affect what we see. The positivist ideal of

theory choice was a situation in which two competing theories made conflicting

observational predictions, a "crucial experiment" was performed, and

one theory won the day while the other was refuted. On Kuhn's view, things are

rarely this simple; often different theories will handle different sets of

observations, and even where in some sense they overlap they may not agree in

their interpretation of what is observed. (The duck-rabbit drawing is helpful

in getting a feel for what Kuhn has in mind here: two people can look at exactly the same drawing and still in some sense see

entirely different things.)

C: No

neutral criteria for theory choice

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, especially chapter IX,

Kuhn appears to suggest that each "paradigm" carries with it a set of

evaluative criteria on which it scores well, so that there are no neutral

criteria that will decide which theory is best.

"In learning a paradigm the

scientist acquires theory, methods, and standards together, usually in an

inextricable mixture. . . . each paradigm will be shown to satisfy more or less the criteria that it dictates for itself and to

fall short of those dictated by its opponent" (pp. 109-110).

In later writing, notably "Values, Objectivity, and Theory

Choice," Kuhn takes what seems to be a more moderate view (though he

claims that this is what he meant all along), holding that there are general

criteria for theory choice on which nearly everyone can agree -- things like

simplicity, scope, coherence with existing theory, etc. But he also argues that

proponents of different theories may well interpret these criteria differently.

This is the most radical of the claims Kuhn makes. He suggests

that scientists committed to different paradigms in a certain sense "live

in different worlds." His view here is a nuanced one; he does not deny

that there is a real world which is not changed by changes in our theories or

paradigms, but nevertheless insists that the world we experience and live in is

changed when our theories change. (For

instance, he argues that until the medieval period, there were no pendulums,

but only swinging objects.)

The enormous impact of Kuhn's work is evident in the changes it

has effected in the vocabulary of the philosophy of

science:

·

"paradigm shift"

·

"paradigm" (formerly confined to linguistics)

·

"normal science"

·

"scientific revolutions"

The frequent use of the phrase "paradigm shift" has made

scientists more aware of, and in many cases more receptive to, paradigm

changes, so that Kuhn's analysis of the evolution of scientific views has by

itself influenced that evolution.

Kuhn's work has been used extensively in social sciences as well

as the natural sciences. Kuhn’s analysis

has been Influential in understanding the history of economic thought, for

example the “Keynesian Revolution,” and in debates in political science.

Further, it suggested the fruitfulness of using the social

sciences to examine the natural sciences.

Notice how much of the early philosophy of science took the form a

“rational reconstruction” and was to a point, “a priori” prescription rather

than close examination of what actual scientists do do. Post-Mertonian Sociology of Scientific

Knowledge is once such examination.

Kuhn's work has also been used in the Arts and Humanities.

I am NOT a Scientific Relativist!

Kuhn himself wish to defend himself

against the charge that his account of scientific progress found in The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions results in relativism. He does so in

his essay "Objectivity, Value Judgment, and Theory Choice." In

this essay, he reiterates five criteria from the penultimate chapter of SSR

that determine (or help determine, more properly) theory choice:

1.

Accurate - empirically adequate with experimentation and

observation

2.

Consistent - internally consistent, but also externally consistent

with other theories

3.

Broad Scope - a theory's consequences should extend beyond that

which it was initially designed to explain

4.

Simple - the simplest explanation, principally similar

to Occam's razor

5.

Fruitful - a theory should disclose new phenomena or new

relationships among phenomena

These, it would seem, demonstrate that some theory choices are

better, more rational than others, that there are absolute standards by which

to adjudicate competing theories and that he is, therefore, not relativist with

respect to science.

But…

Nevertheless, Kuhn then goes on to show how, although these

criteria admittedly determine theory choice, they are themselves

imprecise. Further, in practice they are

used differently by individual scientists, some according

more weight to one aspect over another.

According to Kuhn,

"When scientists must choose

between competing theories, two men fully committed to the same list of

criteria for choice may nevertheless reach different conclusions."

Thus, despite Kuhn’s efforts to prove the contrary, in the end

there remains an irreducibly arbitrariness and irrationality to theory

preference. This being the case, one

still cannot call these criteria "objective." If individual

researchers come to different conclusions, despite the fact then none of them

has done anything “epistemically

improper” (i.e. due to valuing

one criterion over another or even adding additional criteria) then these

conclusions are relative, no one of them objectively better or worse than the

other. It would seem

that, according to this account of scientific practice, there is always

the possibility that there are no absolute principles by which to adjudicate

competing scientific theories (i.e. scientific relativism).

Further still, as Kuhn notes, even this picture presumes the

absence of selfish or other subjective motivations, motivations of which the

scientists themselves may be unaware.

Thus, this may well be, no less than Popper’s, an idealization as

opposed to an account of how actual science proceeds.

Kuhn then goes on to say:

"I am suggesting, of course,

that the criteria of choice with which I began function not as rules, which

determine choice, but as values, which influence it."

Because Kuhn utilizes the history of science in his account of

science, his criteria or values for theory choice are often understood as

descriptive normative rules (or more properly, values) of theory choice for the

scientific community rather than prescriptive normative rules in the usual

sense of the word "criteria", although there are many varied interpretations

of Kuhn's account of science.

The fourth claim listed above, that there is no neutral world,

appears to involve a commitment to some sort of metaphysical anti-realism about

the empirical world, combined with an acknowledgment that there is also a “real

mind-independent world” that is not changed by our changing theories of

it. Kuhn's view here is really very Kantian (except for the view that there can be

different worlds for different paradigms; for Kant there is only one human

"paradigm" and so only one empirical world). He shares with Kant the idea that the really real, independently existing world (for Kant, the

"thing-in-itself") is completely unknowable, and that the empirical

world, the world as we experience it, which is knowable, is partly constructed

by our categories and concepts.

But it is hard to maintain simultaneously the view that there is a

thing-in-itself (a mind-independent world) and the view that we cannot know

anything at all about this world. Just

as the philosophers who followed Kant tended either to be realists who argued

that we can and do know the real nature of things, or to be idealists, who

rejected the idea that there is any such thing-in-itself, so post-Kuhnian

philosophers of science tend to be either straightforward realists who think

that science gives us real, objective knowledge of the world, or anti-realists (such

as social constructionists) who seem to reject the idea that there is a

mind-independent world at all.

Epilog: Found this on a Blog Post:

Personal Footnote: Sometime in the mid 1970s

I was browsing the Philosophy of Science section of Dillon’s the

London University Bookstore. I pulled out Kuhn’s book The Structure of

Scientific Revolutions for a look. A professorial type appeared alongside me

and glanced at what I was reading: he said: ‘Scientific revolutions, my ass’

and walked off. It was Karl Popper.

________________________________________

[1] Popper contended that Marxism began as a genuine scientific

theory, which made bold predictions about the observable future of certain

economic/political systems. However,

when those predictions were observed NOT to come true, Marxists, rather than

admit their theory had been falsified, instead reinterpreted the data in ways

consistent with the truth of their theory, in effect, rendering their theory

unfalsifiable, and therefore, in Popper’s view, removing it from the realm of

genuine “science.”

[2] Think of the Social Conflict Theory as a means of

understanding, explaining and predicting social

history, current societal structures and practices, and future societal

developments. But the paradigm takes as

“given” that all these items can be (must be) understood in terms

of the social conflict which occasions them.

[3] Note this is similar to Quine’s

attack on the analytic/synthetic distinction in his “Two Dogmas of Empiricism”

and Quine’s contention that it is a mistake to think that individual words are

the bearers of meaning independent of the theories (language systems within

which they are being used).