George Berkeley

George Berkeley (1685 – 1753)

- About

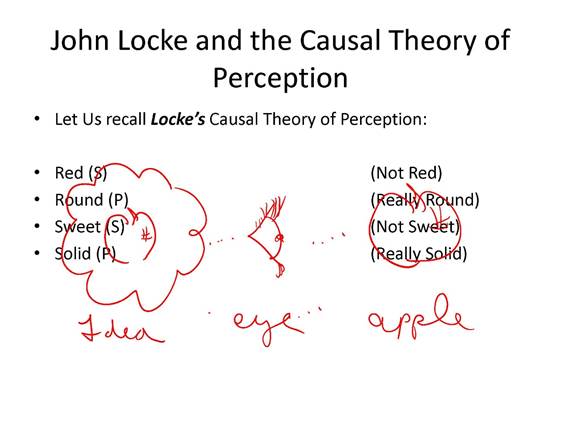

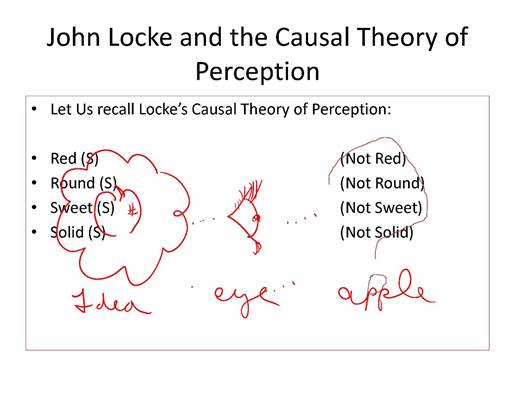

a Generation or so after John Locke (1632 – 1704)

Berkeley agrees with much of Locke, (He

too is an empiricist.), but points out where Locke has made claims that are

inconstant with Empiricism.

1. attacks Locke’s distinction between

primary and secondary properties

2. attacks Locke’s notion of “physical

substance”

3. attacks Locke’s causal theory of perception

1.

Attacks Locke’s distinction between

primary and secondary properties

Recall that Locke claims that “shape”

is primary property because one can’t alter the shape of a thing without

altering the object itself.

But, Berkeley claims one can

alter the shape of the table simply by changing my angle of viewing. This is certainly the case if by shape we

mean “apparent shape.” Artists know this

very well. If you have ever taken a

class in figure drawing of did a still life painting, you know how important it

is to have the same seat each week so that you view the objects from the same

angle constantly.

Notice the different shapes the fork

has depending on how I change my viewing angle.

Now, one might object to Berkeley that

I might be changing the shape the fork “appears” to have, but not I am not

changing the “real” shape of the fork.

But this response illicit on the basis of

Empiricism. It would seem to equate the

“real” shape of the fork with something that I have never seen nor could ever

see- and that is inconsistent with

empiricism’s major claim that “nothing is in the mind which was not first in

the senses.”

So the Empiricist is left with two

options:

Either the (real) shape of the fork is

something that we see or it is not.

A) If it is NOT something we see (perceive), then it was never in our “senses”

and there is no ground to talk about this supposed “idea” at all on Empiricist

grounds. Thus

the Empiricist cannot adopt this view.

B) If shape is something that we see

(perceive), then the (real) shape of the fork is the set of all the perceptions

of the shape of the fork and we do change it merely by changing our angle of

viewing.

Therefore, according to this test

provided by Locke, “shape” is not a primary property, but rather secondary

property.

But recall Locke offers as second test,

that is, whether the property can be accessed by more than one sense or not.

Locke claims that shape is primary

because one can access shape visually and tactilely.

However, this is a

dubious claim at best. On 7 July 1688

the Irish scientist and politician, William Molyneux (1656–1698), sent a letter

to John Locke in which he put forward a problem. The question Molyneux asked was whether a

man, who has been born blind but who had learned to distinguish globes and

cubes etc. by touch, would be able to distinguish these objects simply by

sight, once he had been enabled to see.

Berkeley claims the answer to that

question is definitely “no.” One does

NOT access one and the same property by two distinct senses. Rather one accesses visual shape visually and

tactile

shape tactilely and then

one’s mind correlates the two streams of data, learning through constant

conjunction that objects which look like “this” feel like “that.” (Example: if

a bind person who came to learn cube-shape by touch were later given sight,

could he recognize the cube by sight alone? No, says Berkeley, he would need to

touch the cube is he looking at first to make to coordination.)

Ironically, what we commonly call

“shape” as Locke understands it, is really MORE mind

dependent then visual shape and tactile shape since it is constructed from

these latter by mind.

Therefore, according to Berkeley, there

are NO primary (perception independent) properties. But that means all

properties are secondary properties (perception dependent), and thus

tell us nothing about this “physical substance.”

• Note: Besides, as

Berkeley notes, how can an idea/perception be “like” something that is not that

is not other idea/perception anyway? In

what way can a conscious experience be “like” was is

not conscious experience? Locke claim

that primary properties as they exist in our perception directly “resemble” the

properties as they exist in the object.

But what could this mean?

So while the “real” apple did not have

the properties of red or sweet, according to Locke, at least we can know that

the real apple is round and solid.

However, if ALL properties are secondary properties, then we cannot know

that the “real apple” is round or solid!

But then the “real apple” become a

complete mystery to us.

In fact, the very idea of an aspect of

reality beyond our own direct aquatiance with our own perceptions or “the

mental” is nearly, literally, inconceivable.

2.

Attacks Locke’s notion of “physical

substance”

All this lead

Berkeley to conclude that “physical substance” is a totally unknowable,

mysterious and thus incoherent thing. We can literally know NOTHING about

it. Further physical substance is non‑empirical

“idea” since even Locke admits were never experience

it directly.

§ 19. But,

though we might possibly have all our sensations without them (supposed

physical objects), yet perhaps it may be thought easier to conceive and explain

the manner of their production (our sensations), by supposing external bodies

in their likeness rather than otherwise, and so it might be at least probable

there are such things as bodies that excite their ideas in our minds.

Here Berkeley is acknowledging the

initial appeal of Locke’s theory. While,

strictly speaking, extra-mental objects may not be necessary to account for

mental experience (Think of Descartes’ Dream Argument here.), isn’t it easier

to explain our perception on the presumption of extra-mental objects? Berkeley, responds, “Not at all.”

But neither can this be

said, for though we give the materialists their external bodies, they by their

own confession are never the nearer knowing how our ideas are produced: since

they own themselves unable to comprehend in what manner body can act upon

spirit, or how it is possible it shou'd imprint any

idea in the mind.

This is another instance of the “interaction”

problem that faces by anyone who suggests that mind and body are different

substance which, nevertheless, interact.

How can non-mind affect mind?

Further, how can “mental properties” resemble “non-mental

properties?” But even more so, what sort

of interaction could the interaction between mind and body be? It could not be a non-physical mental

interaction (since it involves the non-mental/ physical bodies) and it could

not be a non-mental/physical interaction (since it involves then non-physical

mind).

Hence it is evident the

production of ideas or sensations in our minds, can be no reason why we shou'd suppose matter or corporeal substances, since that

is acknowleg'd to remain equally inexplicable with,

or without this supposition.

If therefore it were

possible for bodies to exist without the mind, yet to hold they do so, must

needs be a very precarious opinion; since it is to suppose, without any reason

at all, that God has created innumerable beings that are entirely useless, and

serve to no manner of purpose.

§ 20. In short, though

there were external bodies, 'tis impossible we shou'd

ever come to know it; and if there were not, we might have the very same

reasons to think there were that we have now.

Thus, these mysterious “physical

objects” seem neither necessary nor sufficient to account for our mental

experiences. There supposition seems to

be quite beside the point.

Suppose, what no one can deny

possible, (that there could be) an intelligence without the help of external

bodies to be affected with the same train of sensations or ideas that you are,

imprinted in the same order and with like vividness in his mind.

I ask whether that

intelligence hath not all the reason to believe the existence of corporeal

substances, represented by his ideas, and exciting them in his mind, that you

can possibly have for believing the same thing?

Of this there can be no

question, which one consideration were enough to make any reasonable person,

suspect the strength of whatever arguments he may think himself to have, for

the existence of bodies without the mind.

Sum up on Physical Substance

• Since it is totally mysterious.

• Since it is anti-empirical.

• Since it is of no practical/explanatory

use…

Get rid of it!

Thus Berkeley advocates Idealism

Idealism: the only things that exist are ideas, mental objects, and

the minds that perceive them

Locke was a dualist ‑ believes in

two substances mental & physical, Berkeley is a monist[1] ‑ believes

that only one kind of stuff; mental substance

When one speaks of objects and their

qualities, all one is talking about or referring to are past, present, future

or imagined experiences. “Objects” are only what one has seen, is

seeing, will see or would have seen, heard, felt, tasted etc. The world appears the same, indeed the world

“appears” exactly as it “is,” but the metaphysical basis for everything

changes. Since all properties

are perception dependent, Esse est percipi ‑ To be is to be perceived.

Since all properties as perception

dependent, Esse est percipi ‑

To be is to be perceived.

Locke was a dualist ‑ believes in two substances mental & physical, but

Berkeley points out that he runs into the same problems with interaction as

Descartes did. Berkeley is a monist,

that is, he believes that there is only one kind of stuff, mental substance.

But Berkeley is an

Monist Idealist

– (Note:

Materialism/ Physicalism is another kind of monism which contends that there is

only one kind of stuff; material substance.)

But wait…

Now, one might object that the wall of

the classroom is “real and physical, and not just an “idea.” After all, I can’t walk through the

wall. Doesn’t that prove that it is not

just an “idea?”

Not at all according to Berkeley. Of course you cannot

walk through the wall. Why? Because it is SOLID. But what does “solid” MEAN? What one has felt, is feeling, will feel or

would have felt. In other word, “solid”

refers to ideas/ perceptions and nothing else.

English essayist Samuel Johnson

proposes a refutation…

After we came out of the church, we

stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley's ingenious sophistry

to prove the nonexistence of matter, and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal. I

observed, that though we are satisfied his doctrine is not true, it is

impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson

answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he

rebounded from it -- "I refute it thus."[2]

But of course, this is no refutation

whatsoever. It merely shows to

demonstrate that that Johnson did not fully understand the implications of

Berkeley’s epistemology.

3.

Attacks Locke’s causal theory of

perception

Thus it is not the case mysterious

“objects,” whose properties we cannot know “cause” our ideas in ways we could

never explain, and which could not “resemble” these object even if they did

exist. Rather reality is exactly as it

appears to be and therefore perfectly knowable.

• § 38. But after all, say

you, it sounds very harsh to say we eat and drink ideas, and are clothed with ideas. I acknowledge it does

so; the word "idea" not being used in

common discourse to signify the several combinations of sensible

qualities which are called

"things"; and it is certain that any expression which varies from the

familiar use of language will seem harsh

and ridiculous.

• But this doth not concern

the truth of the proposition, which in

other words is no more than to say, we are fed and clothed with those things which we perceive

immediately by our senses.

• § 39. If it be demanded

why I make use of the word "idea," and do not rather in

compliance with custom call them

"thing"; I answer, I do it for two reasons-first, because the term "thing" in

contradistinction to "idea," is generally supposed to denote

somewhat existing without the mind;

secondly, because "thing" hath a more comprehensive signification than "idea,"

including spirit or thinking things as well as ideas.

• Since therefore the objects of sense exist only in

the mind, and are withal thoughtless and

inactive, I chose to mark them by the word "idea," which

implies those properties.

Problems for Berkeley:

Yet the world seems to exist even when unperceived.

You light a candle, go out of the room

for a while and when you come back the candle has burned down.

You go on vacation and forget to have

someone water your plants; when you get back all the plants are dead.

While Locke might have contended that

if a tree falls in the woods and there is no one there to hear it, it doesn’t

not make a sound, he would not deny that the tree

still exists, even when unperceived.

This is because he would say that the physical substance exists

unperceived, possessing primary properties.

But Berkeley insists that this is a

bankrupt theory, incoherent with the tenets of empiricism. There are no primary properties, and we

cannot have knowledge of extra-mental physical substance which would not

explain anything even if some such thing did exist. Thus things cannot

exist unperceived, since to exist at all is to exist as an object of

(someone’s) perception.

Problem:

There was a young man who said

"God

Must find it exceedingly odd

To think that the tree

Should continue to be

When there's no one about in the

quad."

Locke would explain this phenomenon by appealing

to physical substance and primary properties, but Berkeley thinks he has shown

that avenue of explanation to be conceptually bankrupt. All properties occur only in a mind. There are no mind-independent “ideas.”

Berkeley reasons that these phenomena

(the persistence of “objects” when no (finite) mind perceives them) constitute

evidence that SOME (infinite) mind must be perceiving the

world at all times and at all places even when (finite) human mind do

not.

Therefore, experience gives us reason

to suppose that the is some infinite Mind.- i.e. God

Reply:

"Dear Sir: Your astonishment's odd;

I am always about in the quad.

And that's why the tree

Will continue to be

Since observed by, Yours faithfully,

God.” J

Therefore, experience gives us reason

to suppose that there is some infinite Mind.- i.e.

God If one is going to be a good

Empiricist then one has to hold that physical substance is an incoherent. The endurance of the world then is evidence

of God.