Epistemology:

What

do you know?

I

know I have a hand.

I

know that Paris is the capital of France.

I

know that gold’s atomic number is 79.

I

know that a rook can move horizontally or vertically on the chess board.

I

know what a rose smells like.

I

know how to ride a bike.

I

know where I live.

I

know who I am. (most days).

But

all these really refer to importantly different “ways of knowing” or “kinds” of

knowledge. In Western philosophy, we

have concentrated mostly of “propositional” knowledge. By the way, a “propositional belief” is a

“that” belief: I belief that… The “proposition” is what comes after the

“that.” e.g.

that the Earth revolves around the sun, that Tuesday comes after Monday; that the

square root of four is two. So much

emphasis on propositional knowledge has lead

to the impression that all knowledge is propositional and that anything worth knowing can be

expressed in propositions. (Those “that”

phrases I was talking about.) I think

this is a problem, but we’ll be talking more about that throughout the

semester.

Plato

argues that knowledge is best understood as “true, justified belief.[1]” That is to say that Jose knows that Mary is

guilty of cheating on her quiz is to say:

- Jose believes that Mary is

guilty.

- It is true that Mary is guilty.

- Jose has a good reason

(justification) for his belief that Mary is guilty.

Note: Kn=

TJB. This is referred to as the “Traditional Account of Knowledge.”

As

I say, this has been widely accepted as THE correct understanding of

knowledge for the better part of Western history. More recently it has been challenged[2]

and we will be looking both at the traditional account of knowledge and its

challenges. Today I want to concentrate

on how the traditional understanding of knowledge has

Rationalism and

Empiricism

So

how do we acquire knowledge? How do we

avoid deception and error? Plato

suggested that the senses were deceptive, and that the most reliable knowledge

came from a priori reason and introspection. He can point to the reliability of math and

geometry to prove his point. This is

characteristic of one of the two great traditions in Western epistemology: Rationalism.

But

Plato’s best student and best critic was the philosopher Aristotle. In contrast to Plato, Aristotle held that the

best way to come to know objective truth, indeed the ONLY way to come to know

objective truth, is via sensory experience.

This is the second of the two great traditions: Empiricism. These two

viewpoints battled against one another for the next 2000 years.

The

three major tenants of Rationalism are (1) that there exists such a thing as “innate

ideas,” ideas that are in some sense born in us, (2) that the senses are an

unreliable source of knowledge, and (3) that the most reliable source of

knowledge is our a priori reasoning and introspection.

The

three major tenants of Empiricism are (1) the denial of any such thing as

innate ideas, (2) a confidence in the ability of the senses to provide us with

genuine knowledge, and, (3) while a priori reason

is fine as far as it goes, it's extremely limited with respect to giving us

useful knowledge about the world around us, confined as it is to largely

vacuous logical tautologies.

|

Rationalism |

Empiricism |

|

There are

Innate Ideas |

There are no

innate ideas |

|

The Senses

are a poor, unreliable means to knowledge |

The senses

are a reliable, indeed the only means to knowledge. |

|

The most

reliable means to gain knowledge and truth is via a priori reason and

introspection |

A priori reasoning is fine as far as it goes,

but it is very limited as to what it can provide us in the way of

knowledge. The most reliable way to useful knowledge is through

observation and experience. |

|

Representative

Philosophers: |

Representative

Philosophers: |

|

|

Over

time, Empiricism came to dominate philosophy in the United Kingdom, and

eventually the United States. It is this

tradition, I contend, that has had the greatest influence on contemporary

popular thinking about knowledge, truth and

justification in the United States.

There are several features of this view that I would like to highlight

and ask you to examine. The first of

these is the nature of perception.

Locke on Innate

Ideas (a.k.a.: How we DON’T get

knowledge according to Locke)

Both Plato and Descartes appealed to the doctrine of innate knowledge. But Aristotle denied that there was an ‘innate knowledge’ asserting instead the “nothing is in the mind that wasn’t first in the senses.”

Locke agrees with Aristotle on this point. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), he gives a systematic case against innate knowledge, and argues for the Empiricist doctrine that the senses alone are the source of all knowledge.

Empiricists maintain that the only way to come to know the world is through sensory experience. He agrees with Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas[3]- that:

“Nothing is in the mind without first having been in the senses.”

Note: This was called “The Peripatetic Axiom”

It is found in De veritate, q. 2 a. 3 arg. 19. Thomas Aquinas adopted this principle from the Peripatetic school of Greek philosophy, established by Aristotle.

Latin: "Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius in sensu."

Unlike Descartes, who sought absolute, indubitable certainty (Justification must be apodictic.) , the modern Empiricist John Locke was after something more modest: probability/ plausibility. Like modern scientists today, Locke was not looking for beliefs that could be proven true beyond a shadow of a doubt. Rather he is content to call knowledge those things we can demonstrate true beyond a reasonable doubt.

Summary of Locke’s Case Against Innate Ideas:[4]

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), he gives a systematic case against innate knowledge, and argues for the Empiricist doctrine that the senses alone are the source of all knowledge.

“It is an established opinion

amongst some men, that there are in the understanding certain ‘innate

principles’; some primary notions … characters, as it were stamped upon the

mind of man; which the soul receives in its very first being,

and brings into the world with it.” [5]

However, Locke argues we can only perceive color with our eyes. If so, it seems inconsistent to say we have or could have innate knowledge of color. Locke considers those who suggest “that there are certain principles, both speculative and practical, (for they speak of both), universally agreed upon by all mankind“. If this is so, then is seems reasonable to suppose that all people would share certain innate principles.

Locke points out two problems with this argument:

1. Even if certain principles are universally held, that does not follow from this that these principles are innate.

There could be other explanations why certain principles are universally held. But perhaps more problematic…

2. There simply are no such universally held principles.

He considers some very widely held beliefs:

“I shall begin with the speculative, and instance in those magnified principles of demonstration, “Whatsoever is, is,” and “It is impossible for the same thing to be and not to be”; which, of all others, I think have the most allowed title to innate. These have so settled a reputation of maxims universally received, that it will no doubt be thought strange if any one should seem to question it. But yet I take liberty to say, that these propositions are so far from having an universal assent, that there are a great part of mankind to whom they are not so much as known.”

Locke argues that even the law of identity and the law of non-contradiction are NOT universally held. He claims that “children and idiots have not the least apprehension or thought of them“. If this is the case, we seem to be compelled to assert some people will have “principles in their minds” of which they never become aware. But, as Locke puts it, “it seeming to me near a contradiction to say, that there are truths imprinted on the soul, which it perceives or understands not”

But perhaps one need fully functioning rational capacities to fully appreciate these innate ideas which is why children and the mentally impaired do not assent to them. But Locke goes on to critique this defense.

First, he interprets the statement “that all men know and assent to them when they come to the use of reason” in two ways:

1. That reason is used to discover these innate principles.

But this would imply that all knowledge gained from reasoning would then be innate. This would either contradict the innate view that only universally held knowledge (i.e. the law of identity) have innate principles or it implies that knowledge gained by reasoning does not require the discovery of innate principles.

2. When reason is used these principles become apparent.

On this interpretation, Locke has two lines of critique.

But Locke maintains that in actuality, when one is coming to reason as one matures into adulthood, people discover the law of non-contradiction. They

“are indeed discoveries made and verities introduced and brought into the mind by the same way, and discovered by the same steps, as several other propositions, which nobody was ever so extravagant as to suppose innate.”

Since there are no innate ideas, Locke claims that we start life with a blank slate, "tabula rasa.“

This reference may not be as familiar to you as it is to me. I can recall my grandmother talking about taking her “slate” to school. Children in those days would learn their letters and arithmetic on handheld chalkboards, or “slates.” They were sort of the IPADs of the day and much cheaper than paper. A “blank slate” is merely a blank chalkboard, blank, but ready to be written upon and “receive” information. But then again, “chalkboard” too may be a faded cultural reference these day as well. (Sigh.)

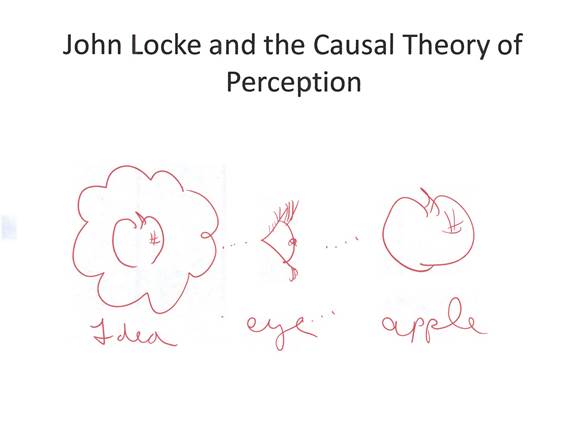

John Locke

and the Causal Theory of Perception (Where do our ideas come from?)[6]

Locke

points out that there is the world and there are our ideas about the

world. He agrees with Descartes

that we never gain direct access to the objective world. He denies “Direct (Naive) Realism.”

This

places critical importance on determining: What is the connection between

reality and our mind? To this end, Locke

offers his “Causal Theory of Perception.”

Causal Theory of Perception

‑

the world interacts with out perceiving organs and causes our ideas in our

minds.

Locke

theory of perception he thought accorded well with the physical theories of his

slightly younger contemporary, Sir Isaac Newton (1642 - 1726). It should be noted that Locke uses the word

“idea” very broadly. Nearly any mental

item can count as an idea: a concept, a memory or even a simple sensation such

as “salty taste.”

·

The only way to come to know the world is through sensory

experience.

·

Agrees with Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas- that,

“Nothing is in the mind without first having been in the senses.”[7]

·

Locke claims that we start life with a blank slate,

"tabula rasa[8]."

·

Points out that there is the

(1) world

and

(2) ideas

about the world.

• Agrees

with Descartes that we never gain direct access to the objective world. He denies “Direct (Naive) Realism.”

This

places critical importance on determining: What is the connection between reality and

our min?

This

this end, Locke offers his “Causal Theory of Perception.”

Causal

Theory of Perception ‑ the world interacts with out perceiving organs

and causes our ideas in our minds; Locke’s use of the word “idea” is very

broadly- nearly any mental item can count as an idea, a concept, a memory or

even a simple sensation such as “salty taste.”

So

then, the world causes our ideas about (perceptions of) it.

Here

is a crude rendering of how this was

supposed to work. You have an object

(say an apple) and it interacts with our perceiving

organs (say our eye) and causes in us the perception of an apple.

Note: our ideas about

reality are different from reality itself; ideas are mental, but reality is

extra mental.

It

is therefore crucial to examine the connection between the two: perceptions and

extra-mental reality in detail. What is the relationship between our ideas and the

world? How does the one give us knowledge about the other? His concerns are not really that different

from those of Rene Descartes here; however, Locke’s resolution is radically

different. Unlike Descartes, who sought

absolute, indubitable certainty (justification must be apodictic), Locke was

after something more modest: probability/ plausibility. Like good scientists today, he was not

looking for beliefs that could be proven true beyond a shadow of a doubt. Rather he is content to call knowledge those

things we can demonstrate true beyond a reasonable doubt.

Our Mental Ideas and the

Extra-mental Reality

Locke is offering a version of “Representational

Realism” The mind does not “directly

perceive the world, but rather only perceives mental representations. What the mind has direct access to then is a

“representation” of reality, but not a direct apprehension of reality as such. Our perceptions are mental representations that are supposed to give us information about the

objective (mind independent) world.

Thus, it is very important to get clear about our

mental content and how we may infer from direct apprehension of our mental

content to claims about the objective, mind-independent world. To this end, Locke offers us certain

distinctions as we sort through the contents of our minds and perceptions.

First, Locke suggests that the world causes our ideas about (perceptions of) it. (Hence his “Causal Theory of Perception”) Next, he begins to examine these ideas and

what their possible relationship to the extramental world could be. He draws several distinctions that he thinks

are important to knowing how we can go from immediate knowledge of our mental

representations to knowledge of mind-independent reality.

Simple and Complex Ideas:

Our

“ideas” come in two varieties according to Locke:

Simple

ideas are idea that cannot be broken down into any component

parts. For example, the idea of

“white.” I cannot explain “white” to

you; I can only show examples of white and hope you get it. Simple ideas arise from simple sensations.

Complex

ideas are ideas that can be broken down into component

parts. For example, the idea of

(perception of) a unicorn. I can

explain the idea of an unicorn to you. To explain a unicorn all one must do is take

the ideas of a horse, white, a horn and combine them in a certain way. The “idea” of an apple (i.e.

one’s perception or experience of an apple) might include the simple ideas of

red, round, sweet, solid, etc.[9]

Primary and Secondary Properties:

Our

experience of objects reveals two kinds of properties: Primary Properties and

Secondary Properties.

Primary Properties

·

Properties of objective, extra-mental reality.

·

These are the qualities of the object independent of who

or whether anyone is perceiving the object. Thus, these are independent of

perception.

These

are the intrinsic features, those they really have, including the "Bulk,

Figure, Texture, and Motion" of its parts. (Essay II viii 9) Since these features are inseparable from the

thing even, when it is divided into parts too small for us to perceive, the

primary properties are independent of our perception of them. When we do

perceive the primary properties of larger objects, Locke believed, our ideas exactly

resemble the qualities as they are in things. He says:

“From this we can easily infer that the ideas of the

primary qualities of bodies resemble them, and their patterns really do exist

in the bodies themselves;[10]

Secondary Properties

These

are NOT, strictly speaking, properties of objects at all, Rather they are properties

of our peculiar experience of reality, that is, of our perception. These properties only occur in the mind of

the perceiver and only at the moment of the

perception. They endure only as long as the perception endures. Thus, these are perception dependent. Think of the pain you experience when you get

a sliver. It is a feature of your experience

of the sliver, but NOT a feature of the sliver.

Alternatively, think of that experiment you probably did in middle

school, where the teacher has you put your left hand in a pan of very warm

water and your right hand in a pan of ice cold water

and between them sits a pan of water at room temperature. Then you were told to

withdraw your hands from both pans and plunge them into the center pan. Your left hand experiences the water as cool, whereas your right

hand experiences the very same water as warm. But this demonstrates that

neither cool nor warm our actual properties of the water, but rather only

properties of your peculiar experience of the water at this

time.

Thus,

these are NOT qualities in the thing itself, but rather evidence powers the

object has to produce in us these ideas of

"Colors, Sounds, Smells, Tastes, etc." (Essay II viii 10) In these

cases, our ideas do NOT resemble their causes, which are, in fact, nothing

other than the primary qualities of the things. The shape of the sugar molecule,

for instance, has the power to create in us a sweet sensation. (Though not in cats.) In these cases, our ideas (e.g.

sweet) do not resemble their causes (e.g. shape).

“It is no more impossible to conceive that God should

attach such ideas to motions that in no way resemble them than it is that he

should attach the idea [= ‘feeling’] of pain to the motion of a piece of steel

dividing our flesh, which in no way resembles the pain.[11]

Tertiary Properties: (Don’t worry

about this too much.)

“because the powers or capacitys of things which too are all conversant about

simple Ideas, are considerd in the nature of the

thing & make up a part of that complex Idea we have of them therefor I call

those also qualities” (Draft A 95: D I 83).

Powers

or capacities are counted as qualities because people tend to think

that they are parts of the natures of things and because the corresponding

ideas are constituents of our complex ideas.

By saying that he “also” calls powers ‘qualities’ (properties), Locke

implicitly contrasts powers with the first sort of qualities. Tertiary quality’ is what commentators call

Locke’s “third sort” of quality (E II.viii.10: 135), which he describes as

“The Power that is in any body, by Reason of the

articular Constitution of its primary Qualities, to make such a change in the

Bulk, Figure, Texture, and Motion of another Body, as to make it operate on our

Senses, differently from what it did before” (E II.viii.23: 140).

The powers,

or tertiary qualities, of an object are just its capacities to cause perceptible

changes in other things.

·

passive power = the capacity a thing has for being

changed by another thing (301), e.g., the power of wax to be melted by the sun.

(We receive the idea of this power from almost all sensible things.)

·

active power = the capacity a thing has for changing

another thing. (301)

For

example the power of sun to melt wax; according to

Locke, these ideas which are the tertiary qualities do not resemble the powers

in things that produce these ideas.

Since only the primary properties of our perception

tell us anything objective about the world we must be

careful to distinguish these from secondary properties. Trying to determine whether or not a object possesses a secondary

property or not, or to what degree is a waste of time since it does not,

cannot, possess it to any degree. (E.g. Is the soup really too salty?) But

then to avoid such silly questions and concentrate on the serious ones, that

is, to engage in serious inquiry it is important we distinguish primary and

secondary properties of our experience.

Two ways to tell the Difference

Between Primary and Secondary Properties:

Since

only the primary properties of our perception tell us anything objective about

the world we must be careful to distinguish these from

secondary properties. Trying to

determine whether or not a

object possesses a secondary property or not, or to what degree is a waste of

time since it does not, cannot, possess it to any degree. Is the soup really too

salty? ( Silly question.) But then to

avoid such silly questions and concentrate on the serious ones, that is, to

engage in serious inquiry it is important we distinguish primary and secondary

properties of our experience.

1.

To change a primary property of the object you have actually

have to change the object itself, but to change a secondary property one

need only change the conditions of perception.

2.

Primary properties can be experienced by more than on sense, but secondary

properties can be experienced by one sense alone.

Consider

the idea (perception) of an apple again:

It

is a complex idea composed of, among other simple ideas, the ideas:

· Red

· Round

· Sweet

· Solid.

According to the criteria Locke provides, which of the

apple’s perceived properties are primary (really “in” the apple, and which are

secondary (perception dependent, having no reality apart from perception)?

So of the four qualities listed above,

which are which?

·

Red is secondary- (I would no longer see red if I were to

change the lighting or I stared at a bright green

poster board. Also

I have access to the color of things through only one sense: vision.)

·

Round is primary- (I would have to cut or smash the apple

to change it’s shape. Also, I have both visual and tactile access

to the shape.)

·

Sweet- secondary.

·

Solid- primary.

So we must be careful about

distinguishing primary and secondary and making claims about reality. Serious inquiry (science) should confine

itself to primary properties alone.

Thus,

for Locke then, we gain knowledge of the objective world via simple sensations

caused in us by the objects which give rise to the simple and complex

ideas. These, in turn, inform us of the

primary properties of the object as well

as provide us with the secondary properties given to us in experience. But there is no point is arguing about

whether an object has a secondary property or not, or to what degree. (In point of fact, they NEVER

have them.)

Notice

there is no point to us arguing about whether the soup is “too salty” or not

since the very same soup may cause in me a “too salty” secondary property, but

in you cause a “not salty enough” secondary property. Salty taste is a perception dependent,

secondary property, existing only in the mind of the perceiver at the time of

perception. As such is it not the proper

subject for serous or scientific discussions.

Further, the very same soup might not even cause in me a “too salty”

sensation next time I taste it if, for instance, I drink something even saltier

than the soup in the meantime or I just get used to the saltiness of the soup. [12]

Since

secondary properties are not actually properties of objects, but rather merely

properties of the perception of objects, they are not fixed and stable. If we had evolved differently, say as

sentient vegetation, “salty taste” would not happen at all. Had we all evolved like snakes, “sound”

wouldn’t happen at all. Though sound waves would continue to be

just as they are. Therefore, serious

inquiry (science) should confine itself to primary properties.[13]

Note: This view of knowledge suggests that the sum

of what can be known are objective facts (facts about primary properties of the

world) and perhaps math. But if you are

not talking about these matters, you are not in the business of saying anything

true or false. Everything else is relegated

to “matters of opinion.” More on this

later.

So,

if a tree falls in the woods and no one is there to hear it, does it make a

sound? No. Had we all evolved like snakes, “sound”

wouldn’t happen at all. – at least our notion of sound. But as I say, sound waves would continue to

be just as they are.

Therefore,

(the new) science (serious inquiry) should confine itself to

primary properties. Recall that Locke is

writing at a time when it was still common for scientists to identify chemicals

by taste.

What

are the “primary properties” properties of?

Locke

realized that there must be some “ground” for these properties. That is, the primary properties must be

property of something. Properties

cannot exist on their own, as Aristotle had noted. If the mind independent apple is really a

solid round something, what is that something?

What, precisely, is solid and round?

So Locke’s answer is that primary

properties (these extra mental, non-perception-dependent properties), were

properties of “Physical Substance.”

Physical

Substance: (Stuff) – but we can know very little about physical

substance as such since we never directly perceive it. We only perceive our perceptions

and these are at most merely primary properties, not the substance itself. Presumably the primary properties of physical

substance are what CAUSE our perceptions, but physical substance in not

accessed directly in perception.

Locke

uses and old metaphysical notion of substance: that of which one

predicates. Nevertheless, since we do

not directly perceive physical substance, there really isn’t much more that we

can know about it. Locke says of

physical substance that it is “something that I know not what.”[14]

“if any one

will examine himself concerning his Notion of pure Substance in general, he

will find he has no other Idea of it at all, but only a Supposition of he knows

not what support of such Qualities, which are capable of producing simple Ideas

in us; which Qualities are commonly called Accidents.[15]

Therefore:

Our

ideas are caused by the physical substance; all ideas are mediated by your

senses; what causes the ideas is the physical substance that never directly

have contact with. While our mental

experience is rich with both primary and secondary properties, the objective

world can only be said to possess the primary properties. Secondary properties would name subjective

experiences only, not the stuff of serious scientific inquiry or discourse

pertaining to objective truth.

This

Empiricist Account of Knowledge and Knowing remained and remains incredibly

influential in Western Concepts of objective knowledge and inquiry. See Logical

Positivism (but you can largely ignore the notes on Emotivism as

the end… unless you are in my Ethics or Aesthetics course.

Addendum:

Locke’s

alternative to the strict Cartesian limitation of knowledge:

The notice we have by our

senses of the existing of things without us, though it be not altogether so

certain as our intuitive knowledge, or the deductions of our reason employed

about the clear abstract ideas of our own minds; yet it is an assurance that

deserves the name of knowledge. If we persuade ourselves that our faculties act

and inform us right concerning the existence of those objects that affect them,

it cannot pass for an ill-grounded confidence: for I think nobody can, in

earnest, be so sceptical as to be uncertain of the

existence of those things which he sees and feels. At least, he that can doubt

so far, (whatever he may have with his own thoughts,) will never have any

controversy with me; since he can never be sure I say anything contrary to his

own opinion. As to myself, I think God has given me assurance enough of the

existence of things without me: since, by their different application, I can

produce in myself both pleasure and pain, which is one great concernment of my

present state. This is certain: the confidence that our faculties do not herein

deceive us, is the greatest assurance we are capable of

concerning the existence of material beings. For we cannot act anything

but by our faculties; nor talk of knowledge itself, but by the help of those

faculties which are fitted to apprehend even what knowledge is.

Locke

then answers Descartes Skepticism:

8. But yet,

if after all this anyone will be so sceptical as to

distrust. his senses, and to affirm all that we see and hear, feel and taste,

think and do, during our whole being, is but the series and deluding appearance

of a long dream, whereof there is no reality; and therefore will question the

existence of all things, or our knowledge of anything: I must desire him to

consider, that, if all be a dream, then he doth but dream that he makes the

question, and so it is not much matter that a waking man should answer him. But yet, if he pleases, he may dream that I make him this

answer, that the certainty of things existing in rerum natura when we have the testimony of our senses for it is not

only as great as our frame can attain to, but as our condition needs. For, our

faculties being suited not to the full extent of being, nor to a perfect,

clear, comprehensive knowledge of things free from all doubt and scruple; but

to the preservation of us, in whom they are; and

accommodated to the use of life: they serve to our purpose well enough, if they

will but give us certain notice of those things, which are convenient or

inconvenient to us. For he that sees a candle burning, and hath experimented

the force of its flame by putting his finger in it, will little doubt that this

is something existing without him, which does him harm, and puts him to great

pain: which is assurance enough, when no man requires greater certainty to

govern his actions by than what is as certain as his actions themselves. And if

our dreamer pleases to try whether the glowing heat of glass furnace be barely

a wandering imagination in a drowsy man's fancy, by putting his hand into it,

he may perhaps be wakened into a certainty greater than he could wish, that it

is something more than bare imagination. So that this evidence is as great as

we can desire, being as certain to us as our pleasure or pain, i.e., happiness

or misery; beyond which we have no concernment, either of knowing or being.

Such an assurance of the existence of things without us is sufficient to direct

us in the attaining the good and avoiding the evil

which is caused by them, which is the important concernment we have of being

made acquainted with them.

9. In summary, then, when our

senses do actually convey into our understanding any

idea, we cannot but be satisfied that there doth something at that time really exist without us, which doth affect our senses,

and by them give notice of itself to apprehensive faculties, and actually

produce that idea which we then perceive.