Experience, Art and

Understanding

- Classical Empiricism’s Passive

Account of Perception Unsatisfactory

- Kantian Theory of Mind as Active

- Experience is not a “Given,” but

rather Constituted by Active Mind

- Gestalt Principles of Perception

A Brief Detour: Locke’s Causal Theory of Perception

John Lock (1632 -1704)

was one of the three “British Empiricists” of the Enlightenment period.

In classical

empiricism, the mind is seen as passive:

John

Locke: the mind is a “tabula rasa”. (Blank Slate)

David Hume (1711 – 1776) refers to mental items as

“impressions.”

Bertrand

Russell (1872 – 1970) talks of “bare particulars”

Note:

the passive

metaphors they use. This is not the

first nor the last time that an unhelpful metaphor for understanding impeded

scientific progress. The impression (humor intended here) that this leaves is

that the mind “simply” receives information during

experience, that perception is a matter of just “seeing what’s really

there.” Knowledge, then, is a matter of

clearly and objectively as possible perceiving the “given.”

You

cannot get much more passive than being an inert rock. So, Locke’s metaphor for mind, a tabula rasa,

is as passive as you can get.

So

then for Locke (and Classical Empiricism generally):

•

The

only way to come to know the world is through sensory experience.

•

We

start life with a blank slate, "tabula rasa."

•

Points

out that

1.

there

is the world … and …

2.

there

are our ideas about the world.

(This put him, somewhat, in league with

Descartes. It raises some of the same

skeptical worries as it did for Descartes, about how reliably our perceptions provide

to us accurate information about the world “as it really is.” …Think “Matrix” type worries here.[1])

·

The world causes our ideas about/ perception

of it.

But

on this model, the mind contributes nothing to this “received”

information. The experience comes

pre-structured and prepackaged. It is a

“given” and clear accurate perception (knowledge) depends upon having an ”innocent

eye,” seeing the objective truth; seeing all and only what is “really there.”[2]

But…

As

widespread as this view of experience became and as influential as this view

was and continues to be, is it accurate?

Immanuel Kant and post-Kantian philosophers suggest the answer is a

definitive, “No.”

All experience is

mediated by Active Mind

This

was not appreciated until relatively recently.

(The myth of the “given” and the “innocent eye” still

persist today.)

Immanuel Kant and

Active Mind

Immanuel

Kant (1724 – 1804) marks an important development in Philosophy and conceptions

of “Mind.” At this point in the history

of Western philosophy, two great opposing traditions had come to an impasse of

sorts: Rationalism and

Empiricism

had both seemed inadequate to account for human knowledge. Rationalism seemed unable to account for

knowledge of our world of experience.

Conversely, Empiricism seemed unable to account for the necessary truths

of math and geometry or even the universality of the laws of nature. Taken to their logical extremes, both epistemological

orientations seemed to end in skepticism (either Descartes’s or Hume’s). Kant’s solution to the impasse was to

revision the very nature of knowledge and experience. The key Kantian insight is that the mind does

not merely receive information in the act of perception; rather the mind shapes

that information and constructs experience out of the raw

sense data it receives. This is

sometimes referred to as Kant’s “Copernican Revolution” in Epistemology. Rather than asking “Is knowledge/

understanding possible?” Kant asks “How is

it that knowledge/ understanding is possible?” Rather than asking “How does

knowledge impress itself onto mind?” (passive

metaphor) Kant asks “How does mind construct knowledge?”

To

accurately account for what is going on in perception it is necessary to see

human experiences as having different content, but a consistent “form.” If we were to abstract all content from human

experience we would arrive at the pure form of

experience. Think of it as blank

template into which mind pours all sensory information and thus arrives at a

coherent experience. Alternatively think

of my (very old, MS DOS based) Maillist program that

can organize records according to one and only one pattern. No matter what data it receives, it will

always organize them in the same fashion according to a single basic template.

In this case it was:

Field 1: First Name, Field 2: Last Name, Field 3: Telephone Number, Field

4: Street Address. Whether the data are

for my mom, my sister, the guy I knew from high school, etc., the record was always be: First Name, Last

Name, Telephone Number, Street Address. Thus I have

knowledge of how my 100th record and any other record will look (in broad

outline) in advance of actually reviewing the 100th record.

That

is, I have a priori knowledge of the 100th record. I know what the first field of my 100th

record is for instance: First Name. My knowledge is not grounded in the particular experience of my 100th record, though it

is grounded in experience in general. After

I get used to my program, and I have seen record after record after record, I

can see the records as having a consisting form with differing content. Now, I cannot make this distinction until I

have looked at the program’s records.

In fact, I cannot make this distinction until after I have look at quite

a few. So, my knowledge of the 100th

record arises from my experience with the program, though it is not grounded in

the experience of my 100th record per se. Further, I do not, nor

could I know what the CONTENT of the record is; but I do know its form. I know the form because when I am referring

to this program’s “records,” I am referring to products of its

organizing function which does not/ cannot change.

In

like manner, Kant claims that claims at after long experience we can make a

similar separation between the varying content of our experiences and their

common form. All our experiences of the world will be of an “external”

“extended: reality that obeys the laws of Euclidian 3-dimensional space. (E.g., the shortest distance between two

points is a straight line.) All our experiences

of the world will be temporally sequential as well. These necessary and universal features of our

experiences are so, according to Kant, not because “That’s how the world really

is,” but rather because that’s the only way human mind organizes experience.[3]

Another

illustration of what Kant has in mind here can be seen in those “Magic Eye”

posters.[4] At one moment they look like flat two-dimensional

images. The next they look like a three-dimensional

image. What is different from one moment

to the next? Is the poster giving you

something different when it looks two dimensional from what it is giving you

when it looks 3 dimensional? No. What is different is what YOU are doing, the activity

of you mind in perception. But this is just a more noticeable example of

what the mind does constantly. The

reason you see reality as three-dimensional is NOT because “that’s how the

world really is,” but rather because that’s how your mind (and every other

normal, healthy human mind) is shaping its sense data. Theoretical physicists might talk of reality

in multiple dimensions, but even they don’t perceive it that way. They come to that understanding purely

theoretically. Perhaps aliens from outer

space perceive reality in more dimensions.

Perhaps God perceives it that way.

But not humans. Not now, not ever,

says Kant. We will always only “image”

the world as three dimensional. And the

same thing goes for unidirectional time.

Kant

is very specific about what these forms and categories of experience are, but

I’ll only refer to a few for illustration purposes.

Space and Time are the

two pure forms of experience according to Kant.

All

human experience will/ must conform to 3-dimensional Euclidian Space.

All

human experience will/ must conform to unidirectional time. (Past to present to future).

Opens the door to

Radical Relativism:

Kant

believed that our (human) empirical knowledge was universal (NOT RELATIVE)

because the pure forms of experience and the categories of thought were

universal for all humans. Therefore, he was certain that what is true for one

human is true for all humans.[5]

BUT....one

might object to Kant’s view.

For

instance, what if we do NOT all put the world together in basically the same

way (e.g., woman according to a female template, men according to a male

template)? If “Men are from Mars and

women are from Venus” then we are not experiencing the same worlds because we are

building our worlds, shaping our experience according to different templates. We are, in a very real sense, living in

different worlds, and truth must be relativized to groups of cognizers who possess the same template. Rather than univalent, truth becomes bivalent

or, perhaps, multivalent. Truth is

potentially as multifaceted as there are minds, and no basis would exist for

claiming that any particular worldview was privileged

among the plurality.[6]

20th

Century Philosopher and Art Historian Applies to Art

Both

Ernest Gombrich (1909 - 2001) and Nelson Goodman (1906-1998)

represent 20th century thinkers who echo the key Kantian Insight:

Mind is NOT passive in experience, but rather active. This insight is crucial to understand what is

going on in art, among a great many other things, they claim. Nelson Goodman, like Kant, denies the

simple/passive view of perception. (There are no “bare particulars;” there are

no “innocent eyes.”) The mind is active

from the onset. The shape and content of experience/perception depend on

the work the mind does (focusing, past experience,

expectations). Perception is a matter of

focusing, ignoring, overlooking, interpreting. Thus, there is no difference between perceiving

and interpreting according to Goodman.

Ernst Gombrich “no innocent eye”

“The

eye comes always ancient to its work, obsessed by its own past and by old and

new insinuations of the ear, nose, tongue, fingers, heart, and brain.”[7]

It does not much mirror the

world as take and make.

Goodman

argued against the persistent myth of the “Pure Empirical Fact.” Classical empiricism would claim that

perception is “automatic,” non-cognitive, or minimally so, merely “biological.” But Goodman insists that perception is NOT

non-cognitive and that what we “see” is a direct result of what and how we’ve

been trained to “read” the world. His

model for perception can clearly be seen in other modes of perception. Consider wine tasting, X-ray reading, hearing

bird calls, and art. Despite the fact that perception

may (seem to) be automatic, there is nothing basic or given in perception.

Nelson

Goodman admits that perception may indeed be automatic, but that does not mean

passive. It does not mean inevitable. Consider the act of hearing a sentence

spoken in your native language. You

cannot help but hear it as a sequence of intelligible (meaningful) sounds.

Though this can be automatic, this is a learned, cognitive skill. You

are interpreting those phonemes whether your realize

it or not. And for those with poor

command of the language, it takes effort.

But for those with good command over the language it is “second

nature.” Automatic perhaps, but nevertheless learned and acquired

actively.

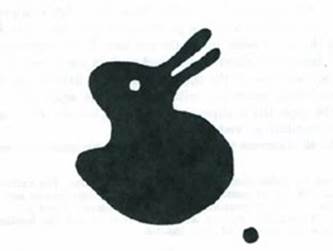

For

another example, think of visually ambiguous images, specifically the

“Duck/Rabbit.”

This phenomena shows why the old model of passive perception

is inadequate for understanding how perception works. For Locke, he thought it was enough to talk

about the object, the perceiving organ and the

perception. On this view the object

“impresses” itself on the mind and the mind is simply the inert passive

recipient of the information.

We

can complicate this simple model a bit by talking about the object, the organ,

the retinal image, and the perception.

But again, on this model, the perception is understood as the inevitable

product of the retinal image. Mind plays

no active role.

But

in the case of ambiguous images, the poverty of this view is revealed. In the case of the “Duck/Rabbit” image, I can

see a duck or I can see a rabbit, that is I can have

the duck-perception or the rabbit-perception and which perception I have cannot

be explained in terms of the object, the organ or the retinal image. When I have the duck-perception, the object,

the perceiving organ and the retinal image are the same as when I have the rabbit-perception. There must be some other factor that

explains the difference in perception, and that factor is the activity

of mind. The old Lockeian model of mind simply cannot

account for the phenomena.

After

Kant theorists argue against passive accounts of mind and knowledge and

emphasizes the role of the faculty imagination in the formation of experience.

This opened the door to the position that there is not merely one right way to

experience or to know. If our experience

of the world is a product of what the world gives us and what we do with it (how

we “image” it) then it follows that there may be as many different experiences

of the world as there are “imagers” and no one is in a privileged position with

respect to its rivals.

This

realization gave rise to the Post-modernists’ notion

that there is no one point of view from which Truth can be determined. Imagine

two groups of people, one who could only see the duck and one that could only

see the rabbit. Which group is seeing

what is “really there” and which group is wrong? Well of course we see in this example that there

is no reason to think that either group is privileged here. Further, the only reason we could have to say

that one of them has truth and the other has falsehood and is not seeing the

world “correctly” would be to advance a political, economic

or social agenda.

Perception: 8 Gestalt

Principles and Bottom-Up verses Top-Down Processing

1.

Distal and Proximal Stimuli vs. Percepts

The root of Distal is clearly

related to the English word distance, and should, I hope communicate

the idea that this it the "outside" stimulus.

Proximal essentially means "near" or "close to", and that root is also used in the English word approximate, which basically means "to make or come close to".

The term Percept comes from

the same root that has a concrete meaning of "to catch" or

"caught". Pretty clearly, it's what we end up with, an identity that

we can use in further processing.

Distal

and Proximal Stimuli vs. Percepts

When

you see somebody walking down a hallway away from you, you don't think that the

person is shrinking, despite the fact that the image

on your retina is doing precisely that. Further, if the person were

shrinking, the image on your retina would be pretty much the same, but you

would likely misinterpret it as the person is moving away for you.

Why?

Well,

one explanation is that because we have adapted to live in the real world and

in the real world that sort of visual simulation is far more often tied to

objects retreating from you rather than staying in a fixed position and

shrinking. This, in effect, is a

perceptual heuristic.

Heuristic:

a

strategy for organizing a great deal of information quickly via a “rule of

thumb” where examining each datum individually is not practical. These are used to control and facilitate

problem solving (in human beings and machines).

Our

visual systems must be able to construct depth information from the 2-d image

that falls on our retina. This requires a perceptual heuristic which Gestalt

theory refers to as “size constancy.” We find depth “cues” and use them to

interpret the retinal image and come up with a depth-independent size. We automatically judge the object of our

perception to be remaining the same size.

This “assumption” is what allows us to further judge its relative speed,

location and trajectory.

These

heuristics a valuable under “normal" life circumstances, but they allow us

to set up all sort of peculiar illusions under “abnormal” circumstances.

For

instance, given two circles of the same size, one surrounded by large circles

and the other by small circles, the circle surrounded by small circles will

appear to be larger. This is because our

visual system uses the size of the surrounding "context" circles as a relative depth cue. Because the circle

with smaller surrounding circles is judged farther away, the size of the circle

itself must be larger.

A

similar situation happens with the so-called Ponzo

Illusion:

The

presence of a “vanishing point” is suggested by an acute angle. It can be enough to make us perceive a size

difference, even between lines of equal length when they differ in distance

from the angle.

In

both cases, the sizes of the retinal

images for the shapes involved are identical (the proximal stimuli

are identical) but our visual system gives us the percept

that the two shapes differ in size.

Since under normal circumstances the presumed distal stimulus

in a three-dimensional scene is further presumed to be larger.

2.

Gestalt Principles (Seven)

1.

Similarity (Perceptual Grouping)

Similar

objects tend to be perceived as “grouped together.” “Similar”

is understood across one or more dimensions (such as color, shape, orientation,

and other simple visual features).

Note that this image is seen as columns of circles and

squares (rather than rows of

“circle, squares”).

To explain this we must refer to

what we are doing with the image, not merely “what it there.”

2.

Proximity (Perceptual Grouping)

Objects

that are closer together are perceived as forming a “group.”

Here

this is seen as rows, not columns.

Interesting

(aesthetically?) things happen, however, when similarity and proximity work

against each other.

In

the last of the three, the images strikes us as

neither/both rows or columns.

3. Good Continuation (Perceptual Grouping)

Objects

or pieces of objects (especially edges and other line segments) are grouped

together to the extent that we can "trace" a good continuation

between the pieces. The Kaniza triangle illusion is a

classic example of this.

Kaniza Illusion

|

|

Name

the beginning and ending points of the lines here.

More

than likely you named a/b and c/d NOT a/c or a/d.

4.

Closure (Perceived Object Shape)

Essentially

a form of Good Continuation; there is

a tendency to "close up" the boundaries of objects even when there

are small gaps or openings.

Here

we tend to see three broken rectangles (and a lonely shape on the far left)

rather than three 'girder' profiles (and a lonely shape on the right). In this

case the principle of closure cuts across the principle of proximity, since if

we remove the bracket shapes, we return to an image used earlier to illustrate

proximity...

5.

Symmetry (Perceived Object Shape)

Everything

else being equal, we prefer to group objects so as to

make symmetrical forms rather than asymmetrical forms. The symmetrical areas tend to be seen as figures against

asymmetrical backgrounds.

6.

Smallness

Smaller

areas tend to be seen as figures against a larger background. In the figure below

we are more likely to see a black cross rather than a white cross within the circle

because of this principle.

As

an illustration of this Gestalt principle, Coren,

Ward and Enns (1994, 377) argue that it is easier to see Rubin's vase when the

area it occupies is smaller. The lower portion of the illustration below offers

negative image versions in case this may play a part. To avoid implicating the surroundedness principle I have removed the

conventional broad borders from the four versions. The Gestalt principle of

smallness would suggest that it should be easier to see the vase rather than

the faces in the two versions on the left below.

Then

there is the principle of surroundedness,

according to which areas which can be seen as surrounded by others tend to

be perceived as figures.

Now

that we are in this frame of mind, interpreting the image shown above should

not be too difficult. What tends to confuse observers initially is that they interpret

the white area as the ground rather than the figure. If you couldn't before,

you should now be able to discern the word 'TIE'.

7.

Common Fate (Perceptual Grouping and Perceived Object Shape)

Objects

are grouped together to the extent that they are perceived as

"traveling" together. This is most literally true when they are all

moving in the same direction or along some common path.

8. Pragnanz The over-riding law of Gestalt Grouping is that we group objects to obtain the "best" or most parsimonious interpretation. Unfortunately, this term is very hard to translate from the German.

Top-down vs. Bottom-up

processing

We

must get clear on the distinction between top-down and bottom-up

processing.

The

notion of "bottom-up” implies effects

seen early in processing, where our previous experience or acquired conceptual

frameworks about the world plays little role.

For

abilities like object recognition, word recognition, and

face processing, however, our previous experience and acquired arsenal of

concepts is not only very important, but influences

our perception; This then is top-down processing.

Interestingly,

top-down effects are most clearly seen when they are absent. The very same

arrangements of chess pieces on a game board (or even the pattern of Xs and Os

in a game of tic-tac-toe) are actually either

perceived as meaningful units (for an expert who has background

learning which admits a meaningful interpretation) or as random (for one who

lack such a background).

Because

of the role that the Gestalt plays, knowledge, perception

and memory are affected. Notice that

knowledge, perception and memory for meaningful

configurations are superior to that for random ones.

Similar

effects can be measured for the ability to recognize crudely scrawled letters

or mumbled phonemes when they occur in the context of a word or “meaningful”

sentence. This is why

people were able to “hear” all sort of things when music recordings were played

in reverse (back-masking). It misses the

point to ask, “But is that really what’s there?” since the

implication of the research is that it’s never “there,” but only up here

(I’m pointing to my cranium now.)