Philosophy

of Mind (Intro)

What

is the “Mind?”

The

(Outright) Rejection of Dualism Itself:

Physicalism

Physcialism

is the metaphysical position that there is only one kind of substance (Monism) and that substance is physical. Alternatively, it is the view that the only

things which exist are physical objects and physical forces. It follows from this view then that either

minds are physical (objects, forces, or operations of physical objects and

forces) or they do not exist at all.

Philosophers of recent years—and nearly all

psychologists—have taken a dim view toward dualism in any form. They have sought a resolution the mind/body

problem consistent with physical.

Species

of Physicalist Accounts of Mind

5.

Functionalism:

The Mind and the Computer

7. Final

Notes

John

Watson (1879 – 1958) began what he called

behaviorism.

Best-known behaviorist is B. F. Skinner (1904 – 1990).

Behaviorism, as a form of science, refuses to consider any events that cannot be

publicly

witnessed. This logically excludes (non-physical) mental events.

Strictly speaking,

as a scientific

method, Behaviorism does not explicitly deny the

existence of immaterial mental events or immaterial mental “substance.”

Note: Metaphysical Theory about the

possible or actual existence of an immaterial the soul does not strictly follow

from this thesis about the (proper) objects of scientific investigation.

But Watson himself suggested that belief in

consciousness goes back to the ancient days of superstition and magic. He concludes that our concept of

consciousness is NOT merely complicated and confused but rather that

there could not possibly be any such thing.

He claimed that this "scientific"

approach is the only alternative to being a mere "savage and still

believing in magic."

"no one has

ever touched a soul, or seen one in a test tube, or has in any other way come

into relationship with it as he has with the other objects of his daily

experience."[1]

Gilbert

Ryle (1900 – 1976)

"The Dogma of the Ghost in the

Machine"

(following some Ludwig Wittgenstein) The Concept of Mind (1949)

First chapter "Descartes' Myth"

Ryle describes what he calls "the

official doctrine":

1. With the doubtful exceptions of idiots and

infants in arms every human being has both a body and a mind.

2. After the death of the body his mind may

continue to exist and function.

3. Bodies are:

a. in space and are

subject to the mechanical laws.

b. can be inspected

by external observers.

4. Minds are

a. not in space.

b. not subject to

mechanical laws.

The following are said to be properties of

mental events that are not properties of physical events

5. Private and Privileged: Only I can take

direct cognisance of the states and processes of my

own mind. (i.e. mental events are unmediated)

6. Privileged, Private

and Incorrigible: One has direct and unchallengeable cognisance

of at least some of the episodes of one’s own private history. (i.e. mental events are private)

7. One can be directly and authentically

apprised of the present states and operations of one’s mind through

introspection. (i.e. metal events are known through

introspection and incorrigible)

8. While one may have uncertainties about

events in the physical world, one cannot have similar uncertainties about (at

least part) of what is momentarily occupying his mind. (i.e.

mental events are incorrigible) A person's present thinkings,

feelings and willings, his perceivings,

rememberings and imaginings are intrinsically "phosphorescent";

The

problem occurs for the official position of how a

person's mind and body influence one another.

Transactions

between the private history and the public history remain mysterious since, by definition, such transactions belong to

neither series.

Thus:

a. They can be inspected neither by

introspection nor by laboratory experiment.

b. They have no ontological status since they

cannot have the status of physical existence nor the status of mental

existence.

It

is supposed some existing is physical existing, other existing is mental

existing.

1. What has physical existence

a. is

in space and time;

b. is

composed of matter, or else is a function of matter.

2. What has mental existence

a. is

in time but not in space.

b. consists

of consciousness, or else is a function of consciousness....

Ryle

argues that the "official doctrine" is an "absurd"

"category mistake":

“It is not merely

an assemblage of particular mistakes. It is one big mistake and a mistake of a

special kind. It is, namely, a category-mistake.”

I must first

indicate what is meant by the phrase "Category-mistake." This I do in

a series of illustrations.

A foreigner

visiting

He was mistakenly

allocating the University to the same category as that to which the other institutions

belong....

Similarly, one may

say that he bought a left-hand glove and a right-hand glove, but not that he

bought a left-hand glove, a right-hand glove and a pair of gloves. [2]

The

Dogma of The Ghost in the Machine

·

There exist both bodies and

minds;

·

There occur physical processes and

mental processes;

·

There are mechanical causes of

corporeal movements and there are mental causes of corporeal movements.

Ryle argues that all these conjunctions are

absurd.

Note: he is not denying that there are

mental processes. He is saying that the phrase "there occur mental

processes" does not mean the same sort of thing as

"there occur physical processes," and, therefore, that it makes no

sense to conjoin or disjoin the two.[3]

How are we to understand “metal” states/

processes? Ryle's answer depends on the

concept of a disposition.

Disposition: a tendency for

something to happen given certain conditions. (For example, when I say that the

glass is fragile, that is only to say that it is disposed to break if struck.)

Key is the “if... then” (or "hypothetical") form of the statement.

Ryle explains this in the following way:

He distinguishes two senses of

"explained";

We see the glass is broken and ask “Why is

the glass broken?”

One might say, “Because it was struck by a

rock.” But what if I challenged this explanation

by pointing out that the brick wall was also hit by a rock, but it did not

shatter. The person explaining would

have to add to the explanation that glass is fragile (and brick is not).

So here we find two different senses of

explanations: Causal and Dispositional

1.

Causal sense of explanation: namely

the event which stood to the fracture of the glass as cause to effect.

2.

Dispositional sense of explanation: an

existing law-like proposition indicating the disposition for the thing to

behave in a certain way under certain circumstances. In adding that glass is fragile, one gives a

"reason" for the glass breaking when struck.

The glass is fragile is shorthand for the

following dispositional conditional:

If the glass is

struck by a rock, it will shatter.

The event in question satisfies the protasis (antecedent)

of the general hypothetical proposition, and when the second happening, namely

the shattering of the glass, satisfies its apodosis.

Granted, this is sort of a shallow

“explanation” however, to say it broke when struck because it was “such as to

break when struck.” Still, useful to know that something is fragile.

Ryle’s main idea is this. "Mental" attributes really indicate

dispositions to behave in certain ways under certain circumstances.

Brief analysis of “acting from vanity”:

“The statement

"he boasted from vanity" ought, on one view, to be construed as

saying that ‘he boasted and the cause of his boasting was the occurrence in him

of a particular feeling or impulse of vanity.’ On the other view, it is to be

construed as saying ‘he boasted on meeting the stranger and his doing so

satisfies the law-like proposition that whenever he finds a chance of securing

the admiration and envy of others, he does whatever he thinks will produce this

admiration and envy.’

The general argument:

To say that a person knows something, or aspires to be

something, is not to say that he is at a particular moment in process of doing

or undergoing anything, but that he is able to do certain things, when the need

arises, or that he is prone to do and feel certain things in situations of

certain sorts....

Thus to say “She is thirsty.” Is not to

attribute to her some unverifiable subjective or phenomenal state which is the

motivation/ cause of her behavior. It is

merely to say that “If you put a glass of water in front of her, she will drink

it. (And… if you put a glass of Coke in

front of her… and ginger ale, and Materva, …)

Mental talk is just shorthand for what would

otherwise be very large sets of “if/ than” statements about behavior. “I love my wife.” means “I am such as to exhibit love-behavior

towards her. (e.g. If it’s her birthday I will but her a present. I she is

sick, I will seek to give her medicine. If… and so on.)

Ryle's (and Wittgenstein's) logical behaviorism differs from radical behaviorism

1. It is not a theory about behavior and its

causes

2. It is a theory about the language of mind,

about the meaning of "mentalistic" terms such as "wants,"

"believes," "hurts," "loves," "feels,"

and "thinks."

Applying a mental term—attributing a mental

property to a person—is logically equivalent to saying that the person will act

in a certain way under certain circumstances.

Now admittedly the dispositional explanation

is ultimately shallow. We eventually

will want to know why the glass is fragile.

And that may take us to talk of molecules and molecular structure,

etc. Nevertheless, it is useful and

meaningful to know that something is fragile (which is why they mark certain

postal packages with the word “FRAGILE.”) whether I know what accounts for that

or not.

Likewise, knowing that someone is thirsty

(how they will behave if you offer him or her a coke) is useful, but leaves

unanswered for the moment at least WHY they are such as to behave that way. On this view, “I love my wife.” means I (my

body) is in a physical state that is disposed to behave in certain ways. “I

love my wife.” = “I am such as to exhibit love-behavior towards her.” (e.g. If

it’s her birthday I will buy her a present.

I she is sick I will get medicine

for her, etc.). At some point we must

delve into the neuro-physiology to account for why my body behaves is these

ways, but even if I am ignorant of the causal explanation, the dispositional

explanation can be uselful.

Advantages:

1. Eliminates

all mysterious things mental. However complicated the translation from mental

language to behavioral disposition language, the problem of dualism does not

arise.

2. Consistent

account of the causal interaction between mind and body as the causal

connection between a physical state—

a disposition to behave in certain ways—and the actual consequent behavior.

Problems:

1. It

seems utterly absurd to think behavioristically while

talking to a friend or listening to someone talk to us.

2. Behaviorism

becomes pure nonsense in one's own case, when we are trying to understand and

talk about our own mental states (My pain is not the same as my pain behavior. When I say, “I have a headache.” I am NOT

saying “I am such as to take aspirin, or Tylenol, or Acetaminophen …). However therapeutic in psychology[4]

and however powerful as an antidote to Cartesianism, it

cannot be the whole story.

3. Some

mental states affect other mental states. (Behaviorism cannot account for

this.) “She is thirsty.” not only

equates to an infinitely long chain if in/then statements, it is actually more

complicated than that. Behaviorally she

will drink a coke if put in front of her … if she does not believe it is poisoned,

and if she does not believe it is diet Coke and if she is not trying to cut back on

sugary drinks and if she notices the coke and if she

genuinely believes that it is Coke, and….

But note the if/

then language which was trying to translate the mental into the behavior

actually must include more mental talk (believes, wants, notices, etc.)

As one of Watson's early critics commented, "What

behaviorism shows is that psychologists do not always think very well; not that

they don't think at all."

Mind and Body, or more accurately, mental

events and certain bodily events (presumably brain events) are identical.

Anticipated, in a sense, by Spinoza and

Russell with the dual aspect theory.

Unlike the others it tries to tie itself as

closely as possible with current scientific research, and although it is

not a scientific theory itself, it removes any mysterious

"something" such as found in Spinoza and Russell.

The identity theory says that there are

mental events, but they are identical to— the same thing as—certain physical

events, that is, processes in the brain.

Mentalistic terms do refer to something.

Insists that mentalistic terms

("wants," "believes," "loves," etc.) refer to is

not only a mental state, but also a neurological process that scientists,

someday, will be able to specify.

Dualism is eliminated.

"I have a headache" equals

"such and such is going on in my brain." Important:

this is meant to be an ontological reduction, not a sematic

one. I have a headache does not mean

such and such is going on in my brain any more than “Superman saved Lois.”

means “Clark Kent saved Lois.” One might

know the first claim is true without knowing that the second claim is true,

despite the fact that Superman is Clark Kent.

View associated with Australian philosopher J. J. C. Smart:

Jerome

Shaffer (doesn’t agree with the view, but he)

characterizes Identity theory this way:

The sense of

"identity" relevant here is that in which we say, for example, that

the morning star is "identical" with the evening star. It is not that

the expression "morning star" means the same as the expression

"evening star"; on the contrary, these expressions mean something

different. But the object referred to by the two expressions is one and the

same; there is just one heavenly body, namely, Venus, which when seen in the

morning is called the morning star and when seen in the evening is called the evening

star. The morning star is identical with the evening star; they are one and the

same object.

Of course, the

identity of the mental with the physical is not exactly of this sort, since it

is held to be simultaneous identity rather than the identity of a thing at one

time with the same thing at a later time. To take a closer example, one can say

that lightning is a particularly massive electrical discharge from one cloud to

another or to the earth. Not that the word "lightning" means "a

particularly massive electrical discharge ..."; when Benjamin Franklin

discovered that lightning was electrical, he did not make a discovery about the

meaning of words. Nor when it was discovered that water was H2O was a discovery

made about the meanings of words; yet water is identical with H20.

In a similar

fashion, the identity theorist can hold that thoughts, feelings, wishes, and

the like are identical with physical states. Not "identical" in the

sense that mentalistic terms are synonymous in meaning with physicalistic

term, but "identical" in the sense that the actual events picked out

by mentalistic term are one and the same events as those picked out by physicalistic terms.

Advantages

of the Identity Theory.

Interaction avoided. (There exist only the

physical phenomena)

We have here a dualism of language, but not a

dualism of entities, events or properties.

Problems

With Identity Theory

1. Unlike

successful ontological reductions (such as how “a nation” can be reduced to the

sum of its parts acting is a particular way), the two languages are so very

different that there may still be good reason to suppose that the thing(s) they

refer to is/are very different as well.

2. In

the case of the Morning/Evening Star, without Venus’s unique history, there

would be no point to the different ways of referring to it. But physicalistic

and mentalistic terms do not refer to different phases in the history of one

and the same object.

What sort of

identity is intended?

3. The

analogy of the identity of lightning distinguishes two aspects (the appearance

and the physical composition) of a single physical item. Now it is agreed that the appearance to the

naked eye of a neurological event is utterly different from the experience of

having a thought or a pain, but it is still difficult to regard these as

different aspects of “the same thing.”

One might be tempted to say that one is looking at the same event from

“outside” verses “inside,” but strictly speaking this is only a misleading

analogy, rather than an accurate characterization of the relationship between

the mental and the physical.

“Am I free to roam

about inside my brain, observing what the brain surgeon may never see? Is not

the "inner" aspect of my brain far more accessible to the brain

surgeon than to me? He has the X rays, probes, electrodes, scalpels, and

scissors for getting at the inside of my brain. If it is replied that this is

only an analogy, not to be taken literally, then the question still remains how

the mental and the physical are related....”

“... If by X rays

or some other means we were able to see every event which occurred in the

brain, we would never get a glimpse of a thought. If, to resort to fantasy, we

could so enlarge a brain or so shrink ourselves that we could wander freely

through the brain, we would still never observe a thought. All we could ever

observe in the brain would be the physical events which occur in it. If mental

events had location in the brain, there should be some means of detecting them

there. But of course there is none. The very idea of it is senseless.[5]

4. The

problem of the indiscernibility of identicals

resurfaces. Think of the spots that

appear before one’s eyes after a bright flash.

The person aware of a red “after-image” is aware of something, but the

something is not a brain event nor a physical event of any kind. This thing that one sees has a shape and a

color and does not seem match the shape or color of anything in the brain. The red after-image has a shape and color

that no event in my brain has. If he is

not aware of any physical features, he must be aware of something else. And that shows that we cannot get rid of those

nonphysical features.

Shaffer's criticism is based on the principle

is that if two things are identical, then they must have all the same

properties.

But, Shaffer argues, no amount of research could

possibly show that brain processes and thought have the same properties.

Identity Theory proponents would counter that

the identity of brain processes and thoughts is an empirical identity. It is an identity that must be discovered

through experiment and experience. It is not a logical (semantic) identity, as

if the two terms "brain process" and "thought" are synonymous.

Research can and has shown that certain

thoughts are correlated with certain brain processes, but correlation is not yet identity.

Further

Complications for Identity Theory

Token – Token Identity?

Type – Type Identity?

Let’s say that we observed that every time I

heard a C chord you observed I had brain state A, that is, that every token of

C-chord-hearing was conjoined to a token of brain state A. And on this basis we decided that the events

were not merely coordinated, but identical.

The question would still remain: is this Type of mental event equivalent

to that Type of brain event such that, when one (anyone) were in brain state A,

one was hearing a C chord? And if one is

not in brain state A one is NOT hearing a C chord? Is the identity of the type of mental state

identical to a type of brain state and vice versa? Or even me, a year from now,

or having undergone some brain trauma or new learning?)

Note if it were, there is no way my dog or

aliens from outer space (Vulcans) could ever be said to “hear a C chord” –

(have the same mental state as I) since it is biologically impossible that they

ever have the same brain state as I.

But if we deny type – type identity all were

left with is the claim that every mental state is identical to some

brain state, but we cannot determine with any precision which one. This does not really seem to be a very

helpful theory of mind.

Proposes that our increasing knowledge of the

workings of the brain will make outmoded our "folkpsychology" talk about

the mind and we will all learn to talk the language of neurology instead.

Paul

Churchland (1942 - )

Defends utilizing neurological explanations

of human behavior and discarding mentalistic explanations

(contra Identity Theory). He is not

trying to reduce mental talk to brain talk (or map out an equivalency table);

rather he is saying we should simply abandon metal talk as a serious way of

understanding human behavior. He claims

that with increased knowledge of neurology, our ordinary language will be

replaced or, at least, seriously revised:

The identity theory is deeply problematic because

a materialist account of our mental capacities seems unlikely. There seems to

be no “nice one-to-one match-ups” in the offing between the concepts of folk

psychology and the concepts of theoretical neuroscience.

But an intertheoretic

reduction requires one.

Initial Problem was that different physical

systems seem to be able to instantiate the same mental states and certainly the

same functional organization. (Vulcan Brains- Same “memory” on two different

days)

Churchland claims that the one-to-one

match-ups will not be found because our “commonsense psychological framework is a

false and radically misleading conception of the causes of human behavior and

the nature of cognitive activity.”

Folk psychology is a misrepresentation of our internal states and

activities. An inaccurate theory of

behavior (folk psychology) cannot be reduced to an accurate one (neuroscience).

Churchland predicts that the older framework

will simply be eliminated, rather than be reduced, by a matured neuroscience.

Cites historical Parallels

"phlogiston"

Phlogiston was something chemists posited to

explain combustion and corrosion. It

turns out that Phlogiston was not as an incomplete description of what was

going on, but rather a radical misdescription.

Scientific progress does not lead to a “reduction,” but rather to an elimination

of the concept by a mature science.

“The simple

increase in mutual understanding that the new framework made possible could

contribute substantially toward a more peaceful and humane society.”

Arguments

for Eliminative Materialism

Conviction that folk psychology is “a

hopelessly primitive and deeply confused conception of our internal

activities.” [6]

Three

Reasons

1. Widespread

explanatory, predictive, and manipulative failures of folk psychology. (Cannot

really explain sleep, leaning, memory, etc.) Central things about us remain

almost entirely mysterious from within folk psychology. Problems magnify when it comes to pathology

2. Useless

in understanding the effect of damaged brains.

3. Draws

an inductive lesson from our conceptual history. Our early folk theories of

motion were profoundly confused, and were eventually displaced entirely by more

sophisticated theories.

Problems

With Eliminative Materialism

One might claim that eliminative materialism

is false because one's introspection reveals directly the existence of pains,

beliefs, desires, fears, and so forth. Their existence is as obvious as

anything could be.

But the eliminative materialist would reply

that this argument makes the same mistake that an ancient or medieval person

would be making if he insisted that he could just see with his own eyes that

the heavens form a turning sphere, or that witches exist.

The

fact is, all observation occurs within some system of concepts, and our

observation judgments are only as good as the conceptual framework in which

they are expressed.

In all three cases—the starry sphere,

witches, and the familiar mental states—precisely what is challenged is the

integrity of the background conceptual frameworks in which the observation

judgments are expressed. To insist on the validity of one's experiences,

traditionally interpreted, is therefore to beg the very question at issue. For in all three cases, the question is

whether we should re-conceive the nature of some familiar observational domain.

Problems

with Eliminative Materialism:

EM exaggerates the defects in folk

psychology, and underplays its real successes. (Note that every social science

depends on the concepts of “folk psychology” and are nevertheless valuable

account and predictors of human behavior.

So does marketing and advertising.)

Nevertheless the problems with EM serve to

underscore that we are not faced with merely two possibilities here:

1. pure reduction

2. pure elimination.

These are end points of a smooth spectrum of

possible outcomes.

5.

Functionalism: The Mind and the Computer

Since the introduction of computers,

scientific criticisms of dualism have taken another line.

No coincidence that this view arrived during

the “computer age.”

Could, for example, mental processes be based

upon a network of electronic signals in a properly designed complex of

transistors and circuit boards? In other words, could mental processes be the

product of a computer?

Functionalism

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (1926 - ) That minds are

produced not so much by particular kinds of materials, but rather by the relations between parts).

Some functionalists claim that it is, in

principle, possible to build a human mind out of computer parts. Others claim only that the mind is, in

effect, a function of the patterns of neurological activity in the brain.

Crucial distinction between "hardware" (the actual computer

with its circuits) and "software."

(the program that gives the computer specific

instructions to react to stimuli).

According to functionalists, the mind is

nothing other than an elaborate program of sorts, which is the product of a

spectacularly complicated pattern embodied in the physical workings of the

brain.

Behavioral Output is a product of Stimulus and

the “internal” states of the program. This

is how they can account for the fact that sometimes identical stimuli result is

different behavioral outputs (something that the old behaviorists had trouble

with). Thus the

behavioral output of some mental states will depend on other mental states (again,

something Behaviorism couldn’t account for).

Functionalism is similar to

behaviorism, but while behaviorists could not account for the fact that

identical stimulus can result in different behavioral outputs, the

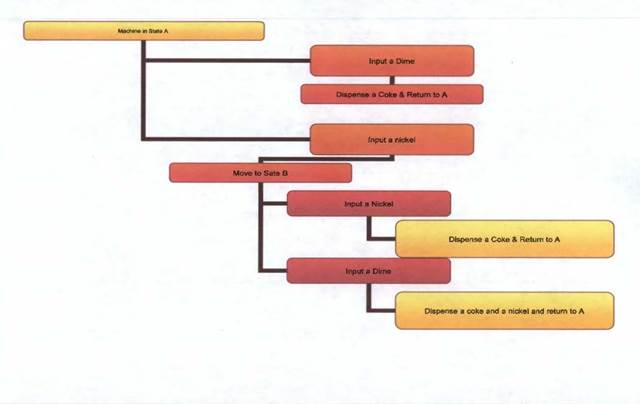

Functionalist can. Consider a coke

machine dispensing bottles of cokes for 10 cents. (It’s a very old machine.)

Sometimes when you input a nickel in the Coke

machine you don’t get a Coke and sometimes you input a nickel you get a coke. Why?

Because sometime the internal state of the machine is at State A (having

zero credit), and sometimes the machine is in State B (already has credit for a

five cents). Depending on the internal

state of the machine, the behavioral output will be different, even given

identical input.

Let’s stipulate that there are only two

possible stimuli:

1. insert a dime

2. insert a nickel.

Let’s further stipulate that there are two

possible “internal” states of this machine.

1. State A

2. State B.

So, if the machine is in State A and I input

a dime. the machine dispenses a coke and remains in State A. If the machine is in State A and I input a

nickel, the machine does not dispense a coke, but moves to State B.

If the machine is in State B and I input a nickel,

the machine dispenses a coke and returns to State A. If the machine is in State B and I deposit a

dime, the machine dispenses a coke and a nickel change and returns to State A.

We can operationally define “believing” as a

set of functions relative to a stimulus.

If the Coke machine believes I've already deposited five cents, this

means that, if I deposit a nickel, it will dispense a Coke and if I deposit a

dime, it will dispense a Coke and 5 cents change. If the Coke machine is in this state, the

Coke machine is in the state of believing that I've already deposited five

cents.

Note that this account of belief need not

appeal to “private internal states” to which the subject has private and

privileged access. These states are just

as public as any other behavioral disposition.

In fact, the subject may not be as aware that she is in this state (of

believing) as well as a third person observer might be. More broadly, understanding “mind” is a matter of mapping the functional

relations between inputs and possible outputs.

John Searle’s Objection to Functionalism

John Searle offers a thought experiment

begins with this hypothetical premise: suppose that artificial intelligence

research has succeeded in constructing a computer that behaves as if it

understands Chinese. That is, it takes

Chinese characters as input and, by following the instructions of a computer

program, produces other Chinese characters, which it presents as output. Suppose, says Searle, that this computer

performs its task so convincingly that it comfortably passes the Turing test:

it convinces a human Chinese speaker that the program is itself a live Chinese

speaker. To all of

the questions that the person asks, it makes appropriate responses, such that

any Chinese speaker would be convinced that they are talking to another

Chinese-speaking human being.

The question Searle wants to answer is this:

does this demonstrate that the machine literally "understands"

Chinese? Or is it merely simulating

the ability to understand Chinese? Searle

calls the first position "Strong AI" and the latter "Weak

AI".

Searle then supposes that he is in a closed

room and has a book with an English version of the computer program, along with

sufficient papers, pencils, erasers, and filing cabinets. Searle could receive Chinese characters

through a slot in the door, process them according to the program's

instructions, and produce Chinese characters as output. If the computer had

passed the Turing test this way, it follows, says Searle, that he too would do

so as well, simply by running the program manually. Searle asserts that there is no essential

difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment.

Each is simply mechanistically following a program, step-by-step, producing a

behavior which is then interpreted as demonstrating intelligent conversation.

However, Searle would not be able to

understand the conversation. ("I don't speak a word of Chinese," he

points out.) Therefore, he argues, it

follows that the computer would not be able to understand the conversation

either. Searle argues that, without

"understanding" (or "intentionality"), we cannot describe

what the machine is doing as "thinking" and, since it does not think,

it does not have a "mind" in anything like the normal sense of the

word.

Therefore, he concludes that "Strong

AI" is false. Further, as two

radically different programs can be functionally isomorphic, even if we were to

create a program that perfectly simulates human cognition, that would not

assure us that we were any closer to understanding actual human cognition.

John

Rogers Searle (1932 - ) attacks the “Functionalist”

understanding of mind. Specifically the

idea that machines can think or that thinking is merely the computational

function of any sort of computing machine.

Connectionists complain that Functionalism is

a "top-down," "software" approach, which can never be

accurate in its representation of the "hardware" of either the brain

or the computer. A functionalist starts

with behavior—either human behavior or computer behavior—and claims that

understanding human consciousness is just a matter of finding the

"program" for that behavior.

Anything ruining that “program” (exhibiting

that behavior) is conscious. The functionalist claims that to understand the

"program" is to understand the behavior, regardless of the mechanical

and physical interactions which make the program run.

The connectionist, on the other hand, claims

that the mechanical and physical interactions that occur in the brain determine

the kinds of behavior—which kinds of software that computers are

capable of processing.

Connectionists advocate a "bottom-up"

approach to understanding the mind.

Note: Connectionists are still

materialists.

Believe that consciousness—in its full color

and quality—is a result of the complicated "connections" that really

do go on in the brain.

But they are also critical of any kind of

strict neurological reduction. There is no

one-to-one correspondence between neurons and thoughts or perceptions;

rather, they claim, the "hardware" of the brain is an immensely

complex mechanism to which the functionalists do not do justice.

7. Final Note: Freud

and the Problem with “Incorrigiblity”

Descartes claimed that what he could

not be wrong about is his seeming to be sitting in front of the fire.

Sigmund Freud introduces the notion of the

“the unconscious” mind. If correct, not

everything mental is knowable, and therefore surely not everything "in the

mind" can be described incorrigibly.

1. We infer the

unconscious from its effects.

2. Same relation to

it as we have to a physical process in another person (except that it is in

fact one of our own).

3. There are ideas

(experiences, intentions) in our minds that we do not and sometimes cannot

know, much less know with certainty.

Thus the traditional notion of the

"incorrigibility" of the mental is seriously challenged.

•

But; one might counter, “If it isn't

knowable incorrigibly then it can't be mental at all.”

•

Could we possibly be wrong in our

confidence that "right now, I am experiencing a cold feeling in my

hand"?

The empiricists assumed that

one could not be wrong about this, for it was on the basis of such certainties

that we were able to construct, through inductive reasoning, our theories about

the world. Consider this example (it

comes from Bishop Berkeley): A mischievous friend tells you that he is going to

touch your hand with a very hot spoon. When you aren't looking, he touches you

with a piece of ice. You scream and claim, with seeming certainty, that he has

given you an uncomfortable sensation of heat. But you're wrong. What you felt

was cold. What you seemed to feel was heat. But even your "seeming,"

in this case, was mistaken.

Sum

Up

Since Descartes' philosophers have struggled

to explain how mind and body worked together to constitute a complete human

being. Certain properties of mind make

the connection between mind and body extremely problematic.

•

Some suggest that mental events and

bodily events are different aspects of some other event (dual aspect theory),

or that they occur in parallel, like the sound and visual tracks on a film (parallelism

or pre-established harmony), or that bodily events cause mental events but

not the other way around (epiphenomenalism), or that mental events and

bodily events are in fact identical (identity theory) or await a mature

neuroscience that will dispense will “mental talk” altogether (eliminative

materialism).

•

Others claim that reference to a

"mental event" is in fact only shorthand for a complex description of

patterns of behavior (logical behaviorsim). Still others hold that the brain is in

fact an extremely sophisticated computer and the mind is causally but not

logically dependent on the brain (functionalism). Lastly, some hold that mind is the unique

biological function of human brain in bodies (connectionism).