Cosmological Arguments: Vertical

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274)

Cosmological Argument: an a posteriori[1]

(empirical, dependent on experience) argument which attempts to prove the existence

of God by claiming that God is a (transcendent) theoretical entity needed to

cause or explains[2] some

observable feature of the world.

William Lane Craig is a contemporary

philosopher who champions the Kalam

version of the Cosmological argument.

This version relies on the premise that the universe is NOT infinitely

old, but rather it is only finitely old.

Thus, it is NOT a “vertical” type of cosmological argument, but rather

an “horizontal” type of cosmological argument. (I am imagining a horizontal

timeline extending from the present backward to some finite point in the

past. The Kalam argument suggest that

since the universe cannot be infinitely old, it must have had a “beginning” in

time and thus a creator.)

Kalam: William Lane

Craig’s formulation/ video production: http://www.reasonablefaith.org/kalam?src=email

But Thomas Aquinas’s version does NOT

rely on the notion that the universe is only finitely old (contra Kalam). Aquinas is willing to accept, for argument’s

sake, that the universe is eternal with no beginning in time. As a Christian, Aquinas does not believe this

of course. As a matter of faith, he

believed that the universe was created by God at some point in the finite

past. However, Aquinas, did not think

that this could be proven philosophically[3][4][5] and so

he does not use this claim in his versions of the cosmological argument.

The early modern philosopher Gottfried

Wilhelm Leibniz (1646 -1716) offers a cosmological argument that is more of an

epistemological argument. He is

reasoning to the thing he believes necessary to explain the world. He suggests that the proposition “The

Universe exists.” is true and is not a self-explanatory proposition. Since the world is not self-explanatory,

there must exist something that is.

But Thomas Aquinas’s versions do not

rely on The Principle of Sufficient Reason (contra Leibniz et al.). St. Thomas Aquinas’ cosmological arguments

are traditional metaphysical arguments. He is reasoning to the thing

which causes the world (NOT the reason that explains

the world a-la- Leibniz). The world is

not “self-caused.” (Indeed, nothing is or could be.) Therefore, it must be caused by something

that is uncaused. And this uncaused

cause must exist simultaneously with its effects. Thus, he offers “vertical” cosmological

arguments.

It’s hard to do “a little Aquinas”

Most contemporary philosophers know that Aquinas believed

that the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, and natural moral law

could be established through purely philosophical arguments. Nevertheless, often his arguments are very

badly misunderstood by those philosophers.

William Lane Craig explains it this way in the opening paragraph of his

chapter on Aquinas in Craig’s doctoral dissertation on the Cosmological

Argument.

Underrated by non-Thomists and

overrated by Thomists, Thomas of Aquino (1225-1274) is one of those

philosophers whom nearly everybody quotes, but whom few understand. Probably more ink has been spilled over his

celebrated “Five Ways” for proving the existence of God than over any other

demonstrations of divine existence, and yet they remain largely misunderstood

today. No doubt this is because these

five brief paragraphs are so often printed in anthologized form and are

therefore read in isolation from the rest of Aquinas's thought. To take these proofs out of their context in

Aquinas's thought and out of their place in the history of the development of

these arguments will tend only to obscure the true nature of these proofs. A proper understanding of Thomas's proofs

necessitates reading them in their immediate context, ferreting out of his

other works the basic epistemological and metaphysical principles they

presuppose, comparing them to similar versions which Aquinas formulated elsewhere,

and relating them to their historical context, particularly to the proofs

propounded, by Aristotle, the Arabic philosophers, and Maimonides. Few modern

philosophers of religion who are not already committed Thomists seem to have

sufficient interest in the thought of a medieval theologian for such an

admittedly arduous task. But this can

only result in neglect of Aquinas's important contributions to the philosophy

of religion or to shallow expositions of his thought, mingled with positive

misunderstandings.

In time, the work of Aristotle waned in

influence with much of his work falling into obscurity in the West. By contrast, his teacher Plato became the

more influential philosopher. Over the

next several centuries Plato's philosophy grew into a kind of a new religion

called "Neo-Platonism." This

world view stressed all the major themes of Plato: the mind/body dualism, the

supremacy of the intellect, the frail and corrupting nature of "the

body." But it also added the idea

that one might be able to achieve a "mystical" union with permanent

transcendent reality through meditation and reflection.

Plato and

Neo-Platonism were widely influential in the Mediterranean, especially in the

early Christian communities. First

Century Jewish theologians living in Alexandria seemed to have been influenced

by these views as were early Christians.

Notice in the Book of John in the New Testament we have

Jesus identified with "The Word" of God (Gr. Logos). This capitalizes on

the earlier Jewish notion that God creates the world through spoken word. Like Plato, this seems to identify

spirituality with "Idea," Word, Law and Command. The Greek equivalent is "Nous" or

"Logos." Philosopher and Church Father, St. Augustine (354 – 430) in particular, who was

tremendously influential in the development of Christian Doctrine, credits

Platonism with helping him understand and accept the Christian Religion. He claimed that the most significant cause of

his resistance and rejection of Christianity was his materialistic conception

of God. (e.g. If God existed, He had to exist as a body, thus limited by space

and time.) Augustine credits Platonism

with enlightening him from this "physicalism" by allowing him to

conceive of immaterial spiritual reality. [6]

All this to say that the early medieval

period was highly Platonist/ Neo-Platonist in nature making it inhospitable for

Aristotelean ideas. Aristotle’s

philosophy, by contrast, had fallen into neglect and disarray in the second

generation after his death and remained in the shadow of the Stoics,

Epicureans, and Academic skeptics throughout the Hellenistic age.

But, while Aristotle was lost to the

Latin west of this period, he was not lost to Arab philosophers and

theologians. They had inherited Greek

ideas once they conquered Egypt and they brought their translations and commentaries

on Aristotle’s philosophy through the Arab West into Spain and Sicily by the

later Middle Ages, which became important centers for this transmission of

these ideas to the Neo-Platonic Christian West. The Arabic theologians and

philosophers also brought with them the cosmological argument along with the

legacy of Aristotle to the Latin West with principle encounters in Muslim

Spain. Christians and Jews lived side by side with Muslims in Toledo, and it

was inevitable that Arabic intellectual life should become of keen interest to

them. A linchpin making this transmission possible was the Jews. Hebrew was so close to Arabic that Jewish

thinkers, many of them writing in Arabic, translated Arabic works into Hebrew

and Latin. And the Christians in turn read and translated works of these Jewish

thinkers.

But recall that Aristotle disagreed

with much that Plato had taught. This

set up a challenge: How to make Aristotle’s Philosophy compatible with the

established and dominant Neo-Platonist Christian theology. Aquinas takes on this challenge.

Tries to synthesize:

1. Christian Neo-Platonism (St. Augustine) & Pagan Aristotelianism

2. Faith & Reason

3. Theology & Philosophy

In general, Aquinas’ work sought to

demonstrate that that if one is a good/efficient philosopher one can/will know

that God exists. Hence faith and reason,

theology and philosophy, far from being antagonistic, actually complement each

other.

His arguments for the existence of God fit

nicely within this framework and are based on one originally drafted by

Aristotle.

·

Aquinas works with

a model originated by Aristotle.

·

Aristotle did not

believe in a creation, but did argue for the existence of an unmoved mover.

Aquinas works this model into his “5

ways” Quinque Viae

Prefatory Remarks About the 1st Way: Argument from Motion

Both

Aristotle and Aquinas talk of an unmoved mover. But the notion of movement was

somewhat broader then we would understand it today. Aristotle believed and Aquinas accepted that

any change was a movement from potentially X to actually X. For instance, if I have a pot of water that

is actually cold, it is nevertheless potentially hot. (It is hot in potency, though not in

actuality.) That is, it could be moved

to being hot. But to move it from

potentially hot to actually hot, there must be something which moves it. In other words, there must be something which

actualizes the pre-existing potentiality.

I will

continue to reference movement since this is the word that Aquinas is using as

did Aristotle. But bear in mind that each had a broader view. Each has metaphysical commitments to doctrines

of “potentiality and actuality.” This

means they were more talking about an unchanging changer or an unactualized

actualizer. Aquinas refers to God as

pure act: Actus Purus. God has no potential. Imagine being God’s high school guidance

counselor. 😊

First Argument ‑ Argument for Motion

The first and more

manifest way is the argument from motion. It is certain, and evident to our

senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion

is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in

potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves

inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of

something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from

potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality. Thus

that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to

be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it. Now it is not possible that

the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same

respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot

simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold.

It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing

should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore,

whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is

put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in

motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to

infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no

other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put

in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in

motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put

in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.[7]

1. Begins with an observation. (Viola! There are moved objects.)

2. In order for any object to be moved it

has to be moved by another.

a. Both of these propositions are evident

through experience.

Can it be an

infinite system (no end)?

Yes…

For every moved

object N, it is moved by another moved object N -1, which in turn is moved by

another moved object N -2, and so on, and so on, and so on.

But…

Can this be the

whole of the story where every mover is a moved mover?

No.

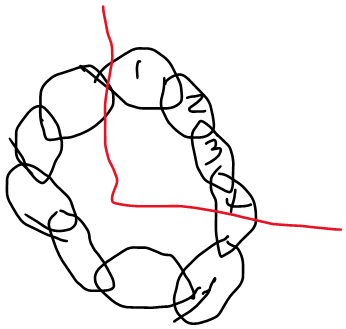

Imagine a bicycle chain that formed a

circle. And we can only see a portion of the chain at a time. Notice in our

imagined situation there is no first link. It is infinite in the sense that there

is no end. No first and no last.

Each link in the chain is moving. And

each link in the chain is moving and being caused to move by being pulled by

the succeeding link. In other words, link A is moving because it's being pulled

by link B which is moving because it's being pulled by link C etc. If this were a chain with 10 links, then link

J is moving because it's being pulled by link A. So on this model, we know what the proximate cause

is for each individual moving link. What we don't know however is what's

causing the entire chain to move.

The links themselves have no

ability to move other things on their own. This ability must be transmitted to the links

in the chain by something outside the chain (transcendent of the system) that

does have the ability to move things. Now

that thing which is transmitting the ability to move things to the links is itself

moved by something, and thus borrows this power from something else, or does not.

If it's borrowing its ability to move

the bicycle chain links from something else, we have the beginnings of an

infinite regress. The only thing that can stop the regress would be something

that transmits the ability to move things, but does not need to borrow that

ability from something else. This is why

Aquinas concludes that, in addition to the moved movers we

observe on a daily basis, there must exist something we do NOT see, an unmoved

mover. Indeed, the very existence of

moved movers confirms the existence of the unmoved mover. There would be no motion at all were there not

an underived source of motion, that is, an unmoved mover.

The suppositions

that there only exist moved movers is unsatisfactory as an account of reality,

since it leaves us with an “infinite regress” and irreducible mystery.

Therefore:

3. It cannot be that every moved object is

moved by another moved object.

Well then that either leads us to the

position that there are NO moved objects (absurd) or that some moved objects

are moved by an unmoved mover which is radically different from that which we

observe on a daily basis. We observe the

“links” in the chain (the moved movers), but this observation rationally compels

us to hypothesize that which we do NOT directly observe, something radically

different than the other moved objects, something outside the

chain (transcendent). This outside mover-force Aquinas calls a Prime Mover and that is God.

The unmoved mover is “Prime” in the

sense of being the current source of all current motion. All the links exhibit derivative motion. If there is derived motion than there must be

a source of motion which is underived.

4. Therefore there exists an Unmoved

Mover.[8]

Now, as previously noted, while

Aristotle and Aquinas are represented most frequently as arguing from literal

“motion,” the argument can be fashioned with reference to any and all sorts of

change. A change is a “motion” from what

a thing was to what it subsequently became.

But for a thing to be changed (e.g. move from potentially hot to

actually hot) it must be changed/ moved by another (e.g. an actually hot fire). But, since this is so, in addition to

changing changers, there must be something which is actual, but did not and

does not change. (An Unchanged changer.)

And of course Aquinas is surely

delighted that this proof seems consistent with certain scriptural passages.

Every best gift,

and every perfect gift , is from above, coming down from the Father of lights,

with whom there is no change, nor shadow of evil.

James 1:17

God did this so

that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he

is not far from any one of us. For in him we live and move and have our being.’

Acts 17: 27 &

28

Second Argument ‑ Argument from

Causality

The second way is

from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is

an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed,

possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so

it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is

not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in

order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate

is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several,

or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore,

if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate,

nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on

to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an

ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly

false. Therefore, it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which

everyone gives the name of God.[9]

1. Begins with an observation. (Voila! There are causes and effects.)

2. Now every effect has its cause. We know that some causes, indeed all the

causes we witness, are the effects of some previous causes. They are caused causes.

Could this chain of

caused causes extend infinitely backwards in time? Yes. says Aquinas,

(Brief

Aside) Accidentally Ordered Causal Series and Essentially Ordered Causal Series

Aquinas and Dun Scotus,

borrowing from Avicenna and Aristotle, say that causes may be ordered in two

ways: essentially or accidentally. As a

case of essentially ordered causes the medievals

typically gave the example of a man pushing a stone with a stick. Accidentally ordered causes were continually

exemplified by a father begetting a son, who in turn begets a son.

These two examples will

serve for discussing the three differences which Scotus proposes between

essentially and accidentally ordered causes:

1. In essentially ordered

causes, the second depends on the first precisely in the very act

of causation. This is not so in accidentally ordered causes.

2. In essentially ordered

causes, there is causality of another nature or order, since the higher is more

perfect. This is not so among accidentally ordered causes.

In a series of

accidentally ordered causes, because they are all of the same kind, they happen

to have to order that they do accidentally.

It is An accident of history that they enjoy the particular ordering

that they do.. Their actual, historical order is accidental. In other words, it could be the hand pushing the stick that

pushes the stone, but it could have just as easily had been the stick pushing

the hand pushing the stone. These are all

derivative causal forces, and where the derivative cause derives

its causal efficacy from the causal efficacy from its (accidental) causal

predecessor. This is what it means to

say that they are all of the same order. They are all derivative causes.

3. All essentially ordered

causes are simultaneously required to cause the effect; accidentally ordered

causes can be successive.

In terms of the two

examples the differences are as follows:

First, in the very act of

pushing a stone, the stick depends on the man to cause it to push; but while it

is true that Isaac depends on Abraham for his existence, he requires no direct

help from Abraham in begetting Jacob.

The second difference is

clear. There is a sense in which the hand-stick-stone

“system “really form a single simultaneous moving system of intermediate

efficient causes ultimately deriving their causal efficacies from the ultimate

uncaused efficient cause, however distant it may be removed from the hand and

the stick. This ultimate cause is a

different, superior, type of cause from which, ultimately, the hand and the stick

derive the efficacy to posh the stone.

Abraham and Isaac, however, are both fathers; neither is a superior type

or kind of cause.

Finally, the third

difference is present in the examples, according to the medievals,

because at the very moment the stick pushes, the man pushes with the

stick. As noted above, there is a

simultaneous unity to the series of the intermediate derivative efficient

causes. Distinguishing the hand, the

stick, and the stone are merely to distinguish nodes in a singular causal

chain. They really do not exist as causal forces independent of one another. By contrast, it is obvious that Isaac does

not beget Jacob at the very moment Abraham begets Isaac.

Aquinas and other medievals suggested that accidentally ordered causes,

might, for all Philosophy can tell,

regress to infinity. But

essentially ordered causes cannot. They must

terminate in a cause of a different and superior kind. Arguments to show this were based on the

three differences mentioned above. For

instance, consider the third difference: Since all essentially ordered causes

are required simultaneously, if there were an infinite regress among them,

there would, at one moment, be an actual completed infinite set of causes. But the medievals

felt Aristotle had shown this to be absurd. The existence of a completed

infinite series is a metaphysical impossibility. Therefore, there can be no infinite regress

among essentially ordered causes. The

sequence must come to a stop at some first cause—which we call God. 😊

Thus a model consisting

exclusively of caused causes would be unsatisfactory for precisely the same

reason as before. This model leads to an

infinite regress. Even an infinite chain

of (intermediate derivative) caused causes requires a cause of a different

order, i.e., that which provides causal efficacy without having to borrow it

from some previous cause, in short, an uncaused cause. Again we must suppose something radically

different from the sort of causes we see on a daily basis, an Uncaused Cause, which causes the system

of causality. This something is

radically different, transcendent, outside the system; A FIRST EFFICIENT CAUSE ‑

GOD

Third Argument ‑ Argument of

Contingent Objects

The third way is

taken from possibility and necessity, and runs thus. We find in nature things

that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated,

and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it

is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be

at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at

one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true,

even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist

only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing

was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to

exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence--which is absurd.

Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something

the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its

necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity

in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been

already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate

the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not

receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This

all men speak of as God.

I chose to render this argument of Aquinas as a Reductio ad Absurdum:

A redutio ad absurdum is an argument technique

where one begins by assuming what one wishes to disprove and then shows how, by

valid inference, it leads to an absurdly false claim.

We know from logic that, when a valid

argument has a false conclusion, then at least one of the premises is false. If we end with falsity, there must be falsity

in our premise set, presumably the assumed premise we are seeking to discredit.

|

|

Premise |

Justification |

|

1 |

There are

contingent objects. |

Viola! (This

rests on observation.) |

|

2 |

Everything which

exists is contingent. |

Atheist

Assumption #1- that there is no Necessary Being- Of course,

Aquinas does not believe this is true.

But does his belief in the existence of a Necessary Being rest only on

his Christian Faith, or is it grounded in Reason as well? |

|

3 |

Everything could

go out of existence. |

Follows from the

conjunction of #1-Definition of Contingent & #2 that everything that

exists is contingent. |

|

4 |

All real

possibilities occur in an infinite amount of time. |

Metaphysical Principle- It seems to follow from reason that, given

enough time anything possible would happen. If after an infinite amount of

time, it still hasn’t happened, then it was never really possible in the first place. |

|

5 |

An infinite

amount of time has occurred. |

Atheist Assumption #2- If one does

not believe in creation, then time stretches infinitely backwards because

there is no beginning. If there was no

creation therefore the universe is infinitely old. Of course

Aquinas does not believe this is true.

But does his belief rest only on his Christian Faith, or is it

grounded in Reason as well? |

|

6 |

All real possibilities have occurred. |

Follows from

4&5 |

|

7 |

Everything has

gone out of existence. –Nothing exists. |

Follows from

3&6 |

|

8 |

There are no

contingent objects |

Follows from 7 |

|

9 |

There are

contingent objects and there are no contingent objects. |

Conjunction of

1&8 |

The conclusion here is a logical

contradiction, and thus, (absurdly) false.

When a valid argument has a false conclusion,

then at least one of the premises is false.

Therefore, Aquinas says that there must

be something which has necessary existence (premise 2 MUST be false).[10] And that necessary being is GOD.

Principle of Sufficient Reason: (From William Rowe)

Rowe suggests that all cosmological

arguments depend on the Principle of Sufficient Reason. For what it’s worth, I agree that it is

operative in Leibnizian type cosmological arguments, but not the other two

kinds (i.e. Kalam and Aristotelian/ Thomistic)

Two Parts:

P.S.R =

a. there is an

explanation for every object.

b. there is an

explanation for every positive fact (why it is as it is and not other than it

is).

Imagine the Universe is an eternal string

of contingent objects (e.g. Chickens) so that history is an infinite series of

contingent objects producing other contingent objects. (e.g. Chickens making

chickens). While every link in the chain

would have an explanation, that is, while every contingent object would be

explained by the model (satisfies PSR

part “A”), there would still be something left unexplained by this model of

reality, namely, “why is it that there are and always have been contingent

objects (chickens)?”(PSR part “B”) Thus, if PSR is true, then there must be a

necessary being, in addition to the contingent beings we witness.

Essentially, this argument asks: “Why

is there something rather than nothing?”

The (best/only) explanation is God:

The First Three of the Five Ways In Sum:

A Thomistic Reading

1. System of objects exhibiting derivative

motion can only exist given a source of motion which is not itself

derivative. Therefore, there must be

some outside (transcendent) unmoved force-mover.

2. System of objects exhibiting derivative

causality can only exist given a source of causation which is not itself

derivative. Therefore, there must be some outside (transcendent) uncaused cause.

3. System of contingent objects

(derivative being) can only exist given a source of existence which is not

itself derivative. Therefore, there must be some outside (transcendent)

necessary being.

A Leibnizian (PSR) Reading

1. System of moved objects is not self‑explanatory therefore there must be some outside

(transcendent) force-mover and that must be God.

2. System of finite causality is not self‑explanatory therefore there must be some outside

(transcendent) cause and that must be God

3. System of contingent objects is not

self-explanatory therefore there must be some outside (transcendent) object and

that must be a necessary being ‑ God

We will not scrutinize the fourth and fifth ways here,

but…

Fourth Argument –

depends on there being objectively true comparative judgements. Therefore there must be a best (Best).

Fifth Argument ‑

Teleological argument. Universe exhibits

intelligent direction, adherence to rational principle. That can only be if it is directed by a being

with intelligence and power, and that must be God.

His Fifth way is often interpreted as a

sort of design argument similar to William Paley. However, I do not believe that it is. I see this as much closer to his others. The universe (and objects in the universe)

exhibit intelligence/ order/ Logos. But

this is a derived intelligence. And if

anything has derived intelligence, then there must be a source of underived

intelligence to bestow it.

Objections to Cosmological Arguments in General and Aquinas’ Ways In

Particular:

1. “Prime Mover,” “First Cause,”

“Necessary Object”‑ Aquinas says we call these “God”, but taken

individually, they certainly are not equivalent to the Theistic O-God. Further, even taken jointly they may fall

short of what religions teach.

Response:

Aquinas is trying to show, like any good empiricist, that it is more reasonable to believe in God, then to

disbelieve or remain agnostic. Given

that we know the universe has a necessary source of being, movement and

causality which is supremely good and intelligent, it is far more reasonable to

be a theist than to be an atheist or to remain agnostic.

2. Principle of Sufficient Reason makes

perfect sense when applied to objects and events within the universe. But it

makes no sense whatsoever when applied to the Universe itself as a whole. The question “Why is there something rather

then nothing?” is a pseudo-question and a category mistake. It assumes that “the universe” belongs to the

category of things with an explanation, but there is no reason to make that

assumption. We should accept the

existence of the Universe as a Brute

Fact. If PSR is denied, specifically as a tool of metaphysics, the

cosmological argument is defanged.

Jean Paul Sartre felt that the universe

was "gratuitous" and Bertrand Russell claimed that the question of

origins was tangled in meaningless verbiage and that we must be content to

declare that the universe is "just there and that's all."

Response: Why should we accept

that the existence of the universe is indeed a brute fact? Isn’t this an arbitrary stipulation

manufactured just to avoid assenting to the existence of God? Further, even some scientists are interested

in asking –perhaps even answering the question: “Why is there something rather

than nothing?”. (e.g. The Grand

Unification Theory Quest of some physicists.)

For

instance Stephen Hawking once wrote:

“…if

we do discover a complete theory, it should in time be understandable in broad

principle by everyone, not just a few scientists. Then we shall all,

philosophers, scientists, and just ordinary people, be able to take part in the

discussion of the question of why it is that we and the universe exist.

If we find the answer to that, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason

– for then we would know the mind of God.”[11]

(emphasis added.)

Further

still, it is not really clear that Aquinas’ argument turns on the Principle of

Sufficient Reason. Notice that Rowe invokes

it, but Aquinas did not mention it.

3. Concepts like “move,” “cause,”

“exist,” “time,” etc. are only concepts that arise from human intellect and

perception and can only apply to human experience. To try to apply these concepts to the world

“as it is,” that is, to the world as uncategorized by the concepts of mind is illicit. It is an attempt to use them outside their

rightful/useful jurisdiction.

For instance, David Hume argues that

causation is a psychological, not a metaphysical, principle, one whose origins

lay in the human propensity to assume necessary connections between

events when all we really see is constant conjunction, contiguity and

succession. If apparent causation is a

psychological propensity and not an objective fact, then we cannot reason to an

objective "Uncaused Cause."

Immanuel Kant echoes Hume here,

somewhat, by arguing that causation is a category of thought built into our

minds as one of the many ways in which we constitute our experience to

ourselves. This has the same, familiar result of limiting the jurisdiction of

"causality" to the realm of human-experience-reality only and not the

mind-independent world.

Response: This is an objection

to metaphysics generally, not an

objection to the particular arguments per

se. As such, a full response would

require a general defense of metaphysics as a legitimate form of inquiry.

Finally:

I found the place in the Critique of Pure Reason where Kant

says that the cosmological argument is dependent on the ontological argument

and can therefore be dismissed as the latter was.

Of the Impossibility of a Cosmological Proof of the Existence of

God:

"But no ens realissimum is in any respect different

from another, and what is valid of some is valid of all. In this present case,

therefore, I may employ simple conversion, and say, every ens realissimum is a necessary being. But as

this proposition is determined a priori

by the conceptions contained in it, the mere conception of an ens realissimum

must possess the additional attribute of absolute necessity. But this is

exactly what was maintained in the ontological argument, and not recognized by

the cosmological, although it formed the real ground of its disguised and

illusory reasoning."[12]

Modern Versions (sort

of):

The “Fine Tuning

Argument”

There are various

versions of this argument proposed with greater or lesser sophistication. I will merely outline the nature of the

argument below. What intrigues me here

is that they seem rather similar to Aquinas’ notions asking, if not “Why is

there something rather then nothing?” they ask “Why is there this

something rather then any of an infinite variety of equally possible

somethings?” Further, even if we cannot

discover the answer to that, doesn’t the type of universe we have itself give

us a clue as to what lies beyond the boundaries of empirical investigation?

Begins with observations:

Our Universe, with its present complexity is a Life-friendly universe. (Viola!)

But, the more we know

about all the many variables that went into the “Big Bang” the more we should

see that OUR Universe as “fine tuned” for “life-friendly.” Altering any one of the variables that

account for the development of our universe, even slightly would result in a universe

devoid of complexity and therefore even the possibility of life. For instance, were the rate of expansion even

slightly faster, the universe would never have developed large clops of stuff

(solar systems, galaxies, planets, etc.), but rather be an endlessly expanding

cloud of hydrogen gas. Or, say the rate

of expansion were only infinitesimally slower, the universe would have simply

collapsed back on itself seconds later.

1.

Let us assume that it is

a fact that that this life friendly universe (and only this life friendly

universe) exists is a positive fact.

2.

Since PSR claims that

every positive fact has an explanation (sufficient reason for why it is so)

then PSR commits us to the idea that there is an explanation for why this life

friendly universe exists.

But notice, nothing within

the life friendly universe can explain this fact, since any and all things

(causes, forces, principles) within the universe are precisely what were trying

to explain.

3.

This being the case, only

something radically different (transcendent) can explain it. And that we call God, as Aquinas might

say.

Well, of course there is

a logical gap between “That which explains the Life-friendly Universe” and “Jehovah” et alia, but that reason and

experience commits us to the notion of a transcendent cause of a life friendly

universe supports a theistic view of reality more than an atheistic view of

reality. Put another way, a life

friendly universe is just the sort of thing you would expect given theism, but

have no particular reason to expect it given atheism. (Buying a one-way airline ticket under an

assumed name is just the sort of thing you’d expect the suspect to do if he

were guilty, but you would have no particular reason to expect this if he were

not guilty.) Therefore, while such

arguments may or may not demonstrate that a Fine Tuner is a necessary

theoretical presupposition of observable fact, if successful they would

demonstrate that (these) observable facts confirm the Theistic Model more than

they confirm the Atheistic Model.