Fideism and Rationality

What is Belief in God after all?

Belief: Standard analysis:

·

Beliefs consist of propositional

content and noetic attitude.

·

Content: what the person believes,

given by a proposition

o

E.g. ‘He believes that elephants are grey.’

·

Attitude: that the person believes

o

(as oppose to

doubts, considers, disbelieves etc.)

“That”

beliefs are beliefs that aims at truth:

·

Beliefs are

true or false (unlike desires)

·

To believe

that p is to believe that p is true.

·

To say ‘I

believe that p’ implies that I take p to be true.

Belief-in

But

consider: “I believe in him.”

This could

mean:

·

I believe

that what he says is true.

·

I believe

that he is trustworthy/sincere.

·

I believe that

he will be successful.

What about: “I

believe in God.” It may be a different kind of belief, arguably not a “that”

belief.

·

Consider: “I

believe in love.” “I believe in the American Spirit”

·

Not a that-

belief (no truth claim), but faith, trust, commitment to an individual or an

ideal

Even so, doesn’t

“belief in” God presuppose a “that belief” (i.e. That

God exists)? You can’t believe in a

person if you think he or she exists.

Nevertheless. you don’t have believe that love exists (literally- as a

mind independent objective reality) to believe in love, or the American

Spirit. Believing in the constitution

could continue even if the actual document were destroyed.

·

Which sort of

belief is religious belief?

·

What is more

basic in religious belief?

·

Should

belief-that be analyzed as (really) belief-in or vice-versa?

·

Is ‘God

exists’ a factual hypothesis about reality?

Debates about

the rational grounds for theism often presuppose that the claim expresses a

belief-that. It is statement capable of

being true or false and the meaning of the statement is connected to this.

This view is

what leads Flew to ask:

·

What

circumstances or tests would lead us to atheism?

·

Still can a

statement be a stamen of empirical fact without us knowing what experiences

would show that it is false? (Flew…No)

But perhaps

falsifying conditions is not what gives ‘God exists.’ its meaning.

·

Not tested

against empirical experience

·

Not purely

intellectual

·

Theism not

acquired by argument or evidence

·

Religious

‘belief’ is belief-in, an attitude or commitment, towards life, others,

history, morality… a way of living.

Perhaps “God

exits.” has some other sort of tie to experience.

Fideism:

Fideism is the epistemological position

that faith is independent of reason, sometimes suggesting that reason and faith

are hostile to each other, and faith is a superior means for arriving at particular truths.

The word fideism comes from fides,

the Latin word for faith, and literally means "faith-ism."

Philosophers have responded in various

ways to the place of faith and reason in determining the truth of metaphysical

ideas, morality, and religious beliefs. A fideist

suggests that reason plays little or no role in religious matters and even is

antithetical to true religious sentiment.

The four most well know theists philosophers who espoused fideism are

Blaise Pascal (1623 – 1662), Soren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855), William James

(1842 – 1910), and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889- 1951).

Sometimes the label fideism is applied

in a negative sense by their opponents.

To evidentialist like William Clifford, Fideism is irrational (in a bad

way) and immoral. Someone like Daniel

Dennett would say it is intellectually irresponsible at a minimum.

There are a number of

different forms of fideism.

From Pascal we get:

The

God of Christians does not consist of a God who is simply the author of

mathematical truth and the order of elements: that is the job of the pagans and

Epicureans. He does not consistent simply of a God who exerts his providence

over the lives and property of people in order to

grant a happy span of years to those who worship him: that is the allocation of

the Jews. But the god of Abraham, the god of Isaac, the God of Jacob, the God

of the Christians is the God of love and consolation; He is a God who fills the

souls and hearts of those he possesses; he is a God who makes them inwardly

aware of their wretchedness and his infinite mercy, who, united with them in

the depth of there soul, makes them incapable of any

other end but himself.[1]

Soren Kierkegaard

Around two centuries later, Soren Kierkegaard

similarly contrasted the God of Christian faith with the God of the

philosophers, in particular, that of Hegel and some of

his Danish followers. The Hegelian

conception of God and history, Kierkegaard thought, at best provides a solution

to a purely abstract problem. What

Kierkegaard desperately sought (and Hegel does not provide) was an adequate

resolution of the problem of personal existence. What is it to be a self-aware being in the

world?

When Kierkegaard claims to be an anti-philosopher,

this is better understood as being an anti-Hegelian. In the philosophical system advanced by

Hegel, without going into too much detail here, the individual was of little or

no importance. The only significance the

individual achieved was as an aspect of constantly unfolding Absolute Spirit. Occasionally some great individual might

arise in history such as Napoleon and embody the “spirit of the age.” But such heroic significant individuals are

relatively rare. The poor schlub in the

field plowing or factory worker at the assembly-line, the common individual,

has little to do with the advance of History and “Geist.” But this anonymizing of the individual mutes

the individual, his struggles, choices, uniquely lived life, his very existence-as-existing.

And while Hegel had thought that all

apparent contradictions (each thesis with its inevitable antithesis) are

subsumed into an evolving dynamic history (synthesis) where both are partially

retained and reconciled, the story of Abraham, Kierkegaard’s own experiences, and, he is willing to bet, the testimony of your own lived

experience as an individual in the world, give lie to this fiction. Kierkegaard the individual, and on behalf of

the individual, wanted to testify to the struggle of choice (Either/ Or) which

is unavoidable in lived life. Abraham

can resolve the conflict, his crisis of faith and paralysis only by making a

choice. Our daily lives are filled with

challenge, hardships, with unrelenting choices to be made.

Both of these criticisms of the Hegelian worldview contribute to

Kierkegaard’s analysis of “Faith.” Also,

it didn’t sit well with Kierkegaard that Hegel is philosophizing about

Christianity while never seriously thinking about being a Christian.

It is

the existing spirit who asks about truth, presumably because he wants to exist

in it, but in any case the questioner

is conscious of being an existing individual human being. In this

way, I believe I am able to make myself understandable

to every Greek and to every rational human being. If a German

philosopher follows his inclination to put on an act and first transforms

himself into a superrational something, just as alchemists and sorcerers

bedizen themselves fantastically, in order to answer

the question about truth in an extremely satisfying way, this is of no more

concern to me than his satisfying answer, which no doubt is extremely

satisfying - if one is fantastically dressed up. But whether a German philosopher is or is not

doing this can easily be ascertained by anyone who with enthusiasm concentrates

his soul on willing to allow himself to be guided by a sage of that kind, and

uncritically just uses his guidance compliantly by willing to form his

existence according to it. When a

person as a learner enthusiastically relates in this way to such a

German professor, he accomplishes the most superb epigram upon him, because a

speculator of that sort is anything but served by a learner's honest and

enthusiastic zeal for expressing and accomplishing, for existentially

appropriating his wisdom, since this wisdom is something that the Herr

Professor himself has imagined and has written books about but has never

attempted himself. It has not even occurred to him that it should be done. Like the customers clerk who, in the belief

that his business was merely to write, wrote what he himself could not read, so

there are speculative thinkers who merely write, and write that which, if it is

to be read with the aid of action, if I may put it that way, proves to be

nonsense, unless it is perhaps intended only for fantastical beings.[2]

Ouch!

From this personal perspective the

conclusions of speculative philosophies and theologies are largely meaningless

verbiage. John Macmurray

explains Kierkegaard’s position well as follows:

The

Danish eccentric, Kierkegaard, discovered that the Hegelian philosophy was

ludicrously incapable of solving - even, indeed, of formulating the problem of

“the existing individual.” If we apply Hegel’s logic to the data of personal

reality, we produce, he showed, “a dialectic without synthesis” for the process

of the personal life generates a tension of opposites which can be resolved,

not by reconciliation, but only by a choice between them, and for this choice

no rational ground can be discovered. He

concluded that we must abandon Philosophy for religion.[3]

To “be” in the world is to be forced to

choose what you shall be, to define yourself. This ultimately compels Kierkegaard to make a

leap of faith.

Faith and the Story of Abraham

Every philosopher we have considered so

far has presumed that what we want is to believe all and only what is rational. Anselm, Aquinas, Pascal, Clifford, James,

Kant, Advocates of the Problem of Evil. What

they would agree upon is that we ought to belief whatever reason most

recommends, whether that is theism or atheism.

By contrast, Kierkegaard says belief in God is not and cannot be

rational, but that doesn’t make it a bad thing.

The time and country he lived in were

largely Christian. His fellow Danes he

regarded as complacent in their religious belief; religious belief amounted to

sort of a daily passionless habit. But

was this real faith? What is

real faith about? Kierkegaard claimed that complacent, thoughtless, routine is

not real faith. Kierkegaard’s philosophy

originated with him brooding over these questions, questions regarding the real

nature of personal faith.

The Abraham Story

Abraham is considered the “father of

faith” by the Abrahamic religions (i.e. Judaism,

Christianity and Islam) because he was held to have had a special relationship with

God. Kierkegaard examines the story of Abraham to discover what “religious

faith” is since those who use the word often point to this story as

illustrative.

http://kingjbible.com/genesis/22.htm

1 And it came to

pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him,

Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am. 2 And he said, Take

now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest,

and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering

upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of. 3 And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took

two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the

burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him.

4 Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and

saw the place afar off. 5 And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder

and worship, and come again to you. 6 And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took the

fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them together. 7 And Isaac

spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said,

Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? 8 And

Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb

for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together.

9 And they came to

the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid

the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the

wood. 10 And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and

took the knife to slay his son. 11 And the angel of the LORD called unto him

out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here

am I. 12 And he said, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only

son from me. 13 And Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold behind

him a ram caught in a thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of

his son. 14 And Abraham called the name of that place Jehovahjireh:

as it is said to this day, In the mount of the LORD it shall be seen.[4]

Story of Abraham

So we see that Abraham had a son, Isaac

whom he loved deeply. How should Abraham

respond to God's apparent command that Abraham take his son out and kill

him? This is a crisis of faith. Further, Kierkegaard cautions us that it is a

mistake to think Abraham merely had to decide whether to do God’s will or

not. Rather, he had to decide what that

“voice in the night” meant. He must interpret the event, give it its

meaning. And various interpretations are

open to Abraham. He must choose to interpret and that choice cannot be “rational” or based

on evidence since it is the making of the choice, the interpretation itself, which

will determine WHAT the “evidence” is evidence of.

"Voice" in the night might

be evidence of:

1. God’s sincere desire?

2. God’s test of Abraham’s morality?

3. A demonic trick?

4. Abraham’s own insanity?

Abraham's choice (and only his choice)

determines what this voice is evidence of.

He MUST choose; his personal choice is the only way to resolve the

issue.

After his choice of interpretation

he must further decide how he will respond to the (newly created) “evidence.”

If this is correct, then, contrary to

what we might initially suppose, we do not base our choices on evidence, at

least not the really important ones, but rather it’s the

other way around; we base evidence on choices.

The voice is not evidence of anything until it is given an

interpretation. What interpretation it

is given is a free (undetermined) choice for

which we are totally responsible.

Further, we can get no rational assistance in making these choices, but

the most important things in our lives rest on them. Nothing is “reasonable” (or unreasonable for that

matter) until after one makes the choices.

This is why in such matters we must abandon

philosophy for faith.

This is why Kierkegaard is considered the founder

of Existentialism.[5]

Existentialism – school of thought founded by Kierkegaard which

stresses individual personal choice and responsibility; major and minor

decisions made in life are your choices; free to choose whatever you will;

complete freedom but therefore total responsibility rest with the

individual. They are matters of creative

self-definition.

Further still, these free existential

choices are the most important choices in life.

Abraham's world, everything important to him (his son, his relationship

with God, his progeny) was riding on this choice. And he is compelled to choose. As Sartre would later say, we are condemned

to be free.

He must therefore make a Leap of Faith

Leap of Faith: a passionate commitment that one makes without regard

to reason, evidence or argument.

This is precisely what Abraham does,

according to Kierkegaard, and this is why he is a hero

of faith. This then is the nature of

true faith. It results from the recognition

of the futility of reason and the necessity for personal unaided choice.

Why then is he, Kierkegaard, a

Christian? The only honest answer anyone

can give is because he chooses to be one- NOT because of supposed evidence for or

against. There is the unknown, and we

can respond to the unknown “God” or “Not God” but this

is a free choice on our part.

“In spite of the

fact that Socrates studied with all diligence to acquire a knowledge of human

nature and to understand himself, and in spite of the fame accorded him through

the centuries as one who beyond all other men had an insight into the human

heart, he has himself admitted that the reason for his shrinking from

reflection upon the nature of such beings as Pegasus and the Gorgons was that

he, the life-long student of human nature, had not yet been able to make up his

mind whether he was a stranger monster than Typhon, or a creature of a gentler

and simpler sort, partaking of something divine (Phaedrus, 229 E). This seems

to be a paradox. However, one should not think slightingly of the paradoxical;

for the paradox is the source of the thinker’s passion, and the thinker without

a paradox is like a lover without feeling: a paltry mediocrity. But the highest

pitch of every passion is always to will its own downfall; and so it is also the supreme passion of the Reason to seek a

collision, though this collision must in one way or another prove its undoing.

The supreme paradox of all thought is the attempt to discover something that

thought cannot think

But what is this

unknown something with which the Reason collides when inspired by its

paradoxical passion, with the result of unsettling even man’s knowledge of

himself? It is the Unknown. It is not a human being, in so far as we know what

man is; nor is it any other known thing….

“The supreme

paradox of all thought is the attempt to discover something that thought cannot

think. This passion is, at bottom, present in all thinking, even in the

thinking of the individual, in so far as in thinking he participates in

something transcending himself. But

habit dulls our sensibilities, and prevents us from

perceiving it”. – Johannes Climacus, Philosophical

Fragments (46)

This quotation explains is found at

the beginning of Chapter 3, The Absolute Paradox. Climacus’ is

explaining paradox in the context of Socrates and human thought. Kierkegaard holds that paradox is “the

passion of thought.” Climacus

believes that at the foundation of all thinking is the idea that the human can

understand and transcend something outside of human rationality. This inherent operating

assumption of inquiry result in humans forgetting the reality that some things,

like God and Christianity, cannot be explained or understood by human thought. Nevertheless, humans still believe they can

comprehend all. (Consider Hegel’s “The rational is the real and the real is the

rational.) The paradox is something that

the mind cannot grasp and understanding that the mind cannot

grasp it is a relevant step in understanding Kierkegaard’s philosophy on

religion.

We want to discover something we

cannot think, even though this will be the downfall of thinking. That which we cannot think is “the unknown,”

and the unknown is God (“the god”). Therefore,

Kierkegaard thinks it foolish to try to prove that God exists, since the very

attempt to do so presupposes that God exists.

We would not try to construct a proof

that something exists if we thought it might not exist. Further, we must begin

with a presupposed notion of the divine nature in order to

attempt any such “proof.” Kierkegaard

argues that the existence of something is never the conclusion of a proof;

rather, it is the starting point. For example, Napoleon’s existence cannot be

the conclusion of an argument starting from his works, because to start with “his

works,” presupposes that he, Napoleon exists and it is

he who performed the works.

Similarly, God’s existence cannot be

the conclusion of an argument based on God’s works. To argue that the events in

the world must derive from an all good being assumes that the events are all

ultimately good and this assumption is based on the belief that there exists an

all-good author of these works. Further

as an a posteriori proof this proof will always leave us in suspense,

give us only a tentative hypothesis as we continue to accumulate more

potentially relevant evidence which may undermine the supposed proof. (Perhaps

a personal tragedy.)

“So let us call

this unknown something: God. It is nothing more than a name we assign to it.

The idea of demonstrating that this unknown something (God) exists, could

scarcely suggest itself to Reason. For if God does not exist it would of course

be impossible to prove it; and if he does exist it would be folly to attempt

it. For at the very outset, in beginning

my proof, I would have presupposed it, not as doubtful, but as certain (a

presupposition is never doubtful, for the very reason that it is a

presupposition), since otherwise I would not begin, readily understanding that

the whole would be impossible if he did not exist.

But if when I

speak of proving God’s existence, I mean that I propose to prove that the

Unknown, which exists, is God, then I express myself badly. For in that case I

do not prove anything, least of all an existence, but merely develop the

content of a conception. Generally speaking, it

is a difficult matter to prove that anything exists; and what is still worse

for the intrepid souls who undertake the venture, the difficulty is such that

fame scarcely awaits those who concern themselves with it. The entire demonstration always turns into

something very different and becomes an additional development of the

consequences that flow from my having assumed that the object in question

exists. Thus I

always reason from existence, not toward existence, whether I move in the

sphere of palpable sensible fact or in the realm of thought. I do not for

example prove that a stone exists, but that some existing thing is a stone. The

procedure in a court of justice does not prove that a criminal exists, but that

the accused, whose existence is given, is a criminal.

OK, so he chooses to be a

Christian. What does that MEAN? He must choose what being a Christian

means. Being a Christian might mean

killing your innocent child. One is not

“done” choosing when one makes a choice to be “X” because, while “X” names a

“kind” you are an INDIVIDUAL. You are

THIS X, and only you decide what being “this X” means. This is the case for any role: father,

mother, son, citizen, Christian, etc. None of these name “fixed essences” or if

they do, then you are not essentially any of them. You are them by choice. (We are all individuals.)

Even one’s assigned features mean

nothing until one chooses for them a meaning.

For instance, I am 5’ 7’’. Some

might say that I did not choose to be this height and there are many other

features that are assigned to me and thus, that I do not freely choose. But the existentialist would counter, and what

precisely does being 5’ 7” mean? I am not “generic” 5’7’ any more than I am

generic philosophy instructor; I am THIS 5’7”

and I choose for myself what that means, that is, what role I choose to

allow it to play in my life.

To further demonstrate the disconnect

between faith and reason, Kierkegaard notes that sometimes Christianity

requires the embracing of two things that are mutually impossible, irrational. For instance, Abraham believed that he would

kill Isaac AND that through Isaac, Abraham would go on to have many

descendants.

Should you be a Christian? Keirkegaard would

ask, “Why are you asking me?” You have to choose what you will be; this is what makes it an “existential”

choice. You create yourself through

such leaps and choices. The idea

that each of us must discover who we “truly are” couldn't be more wrong-headed

from an Existentialist perspective. We

are not a set, fixed anything. We are

the product of our own creation. The real question I must answer is “Who/what

is that I choose to be?”

Kierkegaard claims that religious

faith is of the same character as are any of the really

important decisions we make in life.

They are not made on evidence; they are choices. Religious faith is a non‑rational

commitment irrespective of evidence, argument, or reason. We

believe in God (or believe in NO God) simply because we choose to; such beliefs

can't be based on evidence; what you are looking at doesn't have a meaning

until after you make a choice. Note that

this is not unlike the choice to live a moral or immoral life; this is not

evidence based. We can always

rationalize after the fact, but the reality is that we simply choose to be who

we choose to be. In the end there is

only the “unknown,” and we can respond to the “unknown” and say “God” or say

“Not-God.” Both the Theist and Atheist

are choosing to believe; choice precedes evidence; choice makes

meaning/evidence.

Finally, we must not imagine that once

an existential choice is made, it is over.

Each day requires that we make ourselves anew. For Kierkegaard, the Christian life calls for

constant reaffirmation. Everyday it is a struggle to be a Christian. Similarly, just because I did not cheat the

last time I had an opportunity to, but rather I chose

to be a honest person, does not mean that is the choice I am compelled to make

today. Since every day we are free to

define ourselves, everyday we are compelled to answer

for ourselves “Who am I?” Or perhaps more correctly, who shall I choose to be

today.[6]

As illustrations of the sort of thing

he has in mind, consider two cases; The "Bloody Glove" in the O.J.

Simpson murder case and the Shroud of Turin.

In the O.J. Simpson murder case, a key

bit of "evidence" was a pair of bloody gloves:

Bloody Gloves:

One dark,

cashmere-lined Aris Light leather glove, size extra large,

was found at the murder scene, another behind Simpson's guest house, near where

Brian "Kato'' Kaelin heard bumps in the night.

Mrs. Simpson bought O. J. Simpson two pairs of such gloves in 1990. DNA tests

showed blood on a glove found on Simpson's property appeared to contain genetic

markers of O. J. Simpson and both victims; a long strand of blond hair similar to Ms. Simpson's also was found on that glove.

Prosecution:

Simpson lost the left glove at his ex-wife's home during the struggle and, in a

rush, inadvertently dropped the right glove while trying to hide it; they explained

that evidence gloves didn't fit Simpson in a courtroom demonstration because

the gloves shrunk from being soaked in blood and Simpson had rubber gloves on

underneath.

Defense: glove

behind guest house was planted by Detective Mark Fuhrman, a racist cop trying

to frame Simpson; blood on glove may have been planted by police; underscored

that the evidence gloves didn't even fit O.J. Simpson; (If the gloves don’t

fit, you must acquit.) and the hair analysis isn't sophisticated enough to be

trusted.

What were the gloves

"evidence" of? Well, from a

Kierkegaardian point of view- nothing until you choose to believe. If you choose to believe he is innocent, they

are evidence of a corrupt police plant and frame job. If you choose to believe he is guilty, they

become evidence of his presence at the scene and participation in the

murder. But again, it would be a mistake

to assume the evidence determines what is rational to believe; it is what you

choose to believe that will determine what "evidence" there is.

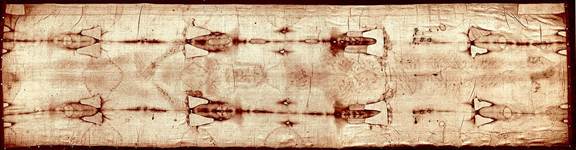

The Shroud of Turin

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth

bearing the image of a man who appears to have sustained wounds and to have

died in a manner consistent with the story of the crucifixion of Jesus. It is housed in the Cathedral of Saint John

the Baptist in Turin, Italy. Historical

records only trace a provenance to about the 1300's. At that time, numerous "holy

relics" and "shrouds" were produced, but whereas these others,

upon closer inspection, could clearly be seen to be fakes, the Shroud of Turin is

intriguing because it was not an obvious fake.

In fact, the image on the shroud could not be made out very well until

it was photographed (circa 1930) and the negative was looked at. When the values are reversed, the image is

much more recognizable and detailed.

Many argued that it was unreasonable to imagine a forger anticipating

the invention of photography. Other

historical accuracies lead many to believe it to be genuine, that is, to be the

cloth that covered Jesus of Nazareth when he was placed in the tomb of Joseph

of Arimathea. Some even suggested that

this image was recorded on its fibers at the time of his miraculous

resurrection.

In 1988, for the first time, the

Catholic Church permitted radiocarbon dating of the shroud by three independent

teams of scientists. Each concluded that

that the shroud was made during the Middle Ages, approximately 1300 years after

Jesus lived. Almost immediately,

spokesmen on behalf of the Roman Catholic Church acknowledged the results,

acquiesced to the judgement of science, expressed their disappointment

and pledged, nevertheless, the take care of the shroud as so many did find it inspiriting,

nevertheless.

Sometime later a group of Protestant

theologians and scientists issued their own statement. They criticized what they thought was an

unnecessary and overly hasty acceptance of this scientific evidence about the

age of the shroud. They argued that if

there were a resurrection (as the Catholic Church and other Christians are

supposed to believe) and if there were at that time a great release of

electromagnetic radiation or the like, (as may seem plausible) then we ought to

expect that the radiocarbon dating process is give us the wrong, much younger,

date.

So, radiocarbon dating suggests that

the shroud is only approximately 700 years old.

What is that evidence of? Does it

prove that the shroud is a fake. Or does it prove that

it is genuine and further is evidence of the resurrection of Christ? Kierkegaard might claim, either. It depends on you. Both require your leap of faith.

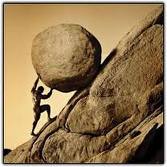

Camus' Myth of Sisyphus (Taken

from my notes on suicide)

One reason some people think that

suicide is wrong is because the noble thing for humans to do is to persevere,

even in the face of meaningless pointless suffering and struggle.

(Existentialism/ Camus Essay "The Myth of Sisyphus")

Existentialists believe that we are

totally free in all are actions and that we are totally responsible for all our

actions. When you try to push your freedom off onto others, this bugs

existentialists. For example, when a salesman convinces you to buy something

overpriced and then you blame him when you find a better deal later ("He

talked me into it… etc.") , existentialists will remind you that you chose

to listen to him and it’s your own fault. You can’t pretend it wasn’t your

choice. Now, there are consequences, and

you may not like those consequences, but it was still your choice. Further,

there are some things that are out of your control, such as your height, but

what these things mean to you is under your control. You assign the meaning to these things and that

meaning is something you chose. There is a sense in which you DO

choose to be that height (again not generic 5’7”, but this 5’7”) because

you choose what being that height means.

You live exactly the life you choose to live.

Soren Kierkegaard, founder of

Christian Existentialism. He comes to existentialism as a way

to understand faith. He understands faith as a choice someone makes.

There is the unknown and we can respond to the unknown by saying “God” or “not

God”, but in either case we’re making a choice and in either case it is a

choice undetermined by evidence.

The Absurd

Later existentialists add to this view

that no one’s "keeping score" (There is no God.) and we’re NOT

immortal. Our death is our total annihilation. All these choices for which we

are responsible and with which we struggle, don’t really matter in the long

run. We’ll eventually die

and we will eventually be forgotten.[7] Our

lives only have the significance that we attribute to them and only for as long

as we have the energy to care. The

“absurd” condition of the human person is that we are compelled to choose,

where choice implies preference, all the while knowing that there is no reason

to prefer one choice over another. We

are compelled to look for meaning in what we know to be a meaningless world.

Some people jumped the gun and thought

well, then I should just kill myself, since there’s no point to my life. But

Albert Camus points out that that is merely another meaningless choice. So, existentialists think we shouldn’t kill

ourselves. Our lives may be full of pointless, arduous struggles, but the noble

thing is to struggle on, even in the face of pointless struggle. It is what we make of our selves

(self-creation) in the struggle that is important. That is the source of our nobility and ending

our lives ends the possibility to "be."

To illustrate his point, Camus retells

the story of Sisyphus. Sisyphus was an

ancient Greek king. To test the love of

his wife, before Sisyphus died, he forbade her from burying his body. (The thinking being is that if she really

loved him, she could not obey this command.)

However, his wife did obey and Sisyphus, annoyed, asked for permission

to return to Corinth to yell at her. He

was granted permission only on the condition that he promise to return, which

he did promise. Once back on the upper

world though, he found he did not want to go back to the land of the dead. He refused though Hades sent several messengers.

Eventually he had to be dragged back kicking and screaming to the underworld by

Hermes. As a punishment for his

disobedience and hubris, Sisyphus was compelled to roll a huge rock up a steep

hill, but before he could reach the top of the hill, the rock would always roll

back down again, forcing him to begin again.

Now for the Greeks, this was Hell, to be tied to unending, meaningless

struggled, to be compelled to labor even when one knows that one's labor will

amount to nothing.

But for Camus, Sisyphus is our hero

and emblematic of the human condition.

We are all tied to arduous struggle, meaningless choices from which we

cannot escape. And why? What was Sisyphus' “crime?” To be.

To live. But if this is the price

of existence says Camus, then it is worth it.

For our nobility arises in what we make of ourselves in the struggle. The struggle with the absurd is result of our

freedom and the source of our dignity.

We must imagine Sisyphus happy, he concludes, for "The struggle

towards the heights itself is enough to fill a man's heart."[8]

William James (1842-1910)

William James is another who thought

that philosophical and theological argument could not be the origin of any

significant religious belief. At best it could provide some logical

clarification of knowledge or beliefs gained from religious experience. We

have already examined James’ notion that the important thing about religious

belief is not whether it corresponds to a mind independent reality, but the

practical role it plays in our lives. As

a pragmatist he is suggesting that truth is what it is good to believe where

“good to believe” can be understood in practical terms. All beliefs are “powers to act” and religious

beliefs are powers to act in religious ways.

“But all these intellectual operations, whether they

be constructive or comparative and critical, presuppose immediate experiences

as their subject-matter. They are interpretative and inductive operations,

operations after the fact, consequent upon religious feeling, not coordinate

with it, not independent of what it ascertains.

The intellectualism in religion which I wish to discredit pretends to be

something altogether different from this. It assumes to construct religious

objects out of the resources of logical reason alone, or of logical reason

drawing rigorous inference from non-subjective facts. It calls its conclusions

dogmatic theology, or philosophy of the absolute, as the case may be; it does not call them science of religions. It reaches

them in an a priori way, and warrants their

veracity.” (VRE 433)

In Persons

in Relation John Macmurray echo’s James’

pragmatic read of religious language.

“For the root of dualism is the intentional

dissociation of thought and action; while religion when it is full-grown

demands their integration. From the point of view of any dualist thought

whether in its pragmatic or its contemplative mode whether from an idealist or

a realist attitude religion cannot even be rightly conceived; and the

traditional proofs even if they were logically unassailable could only conclude

to some infinite or absolute being which lacks any quality deserving of

reverence or worship. The God of the traditional proofs is not the God of

religion.

Among James’

targets were certain contemporary British Absolute Idealists, such as F. H.

Bradley (1846 – 1924). However brilliant

their systems of speculative philosophy might be, they could amount at most to

some largely “meaningless edifying verbiage” with little real religious

significance according to James.

When James

concludes his essay “Will to Believe,” he sounds very close to

Kierkegaard. James quotes from Fitz

James Stephen

"What do you think of yourself? What do you

think of the world?... These are questions with which all must deal as it seems

good to them. They are riddles of the Sphinx, and in some way or other we must

deal with them.... In all important transactions of life

we have to take a leap in the dark.... If we decide to leave the riddles unanswered, that

is a choice; if we waver in our answer, that, too, is a choice: but whatever

choice we make, we make it at our peril. If a man chooses to turn his back

altogether on God and the future, no one can prevent him; no one can show beyond

reasonable doubt that he is mistaken. If a man thinks otherwise and acts as he

thinks, I do not see that any one can prove that he

is mistaken. Each must act as he thinks best; and if he is wrong, so much the

worse for him. We stand on a mountain

pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist,

through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If

we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take

the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether

there is any right one. What must we do? 'Be strong and of a good courage.' Act

for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes.... If death ends all, we

cannot meet death better."

Ludwig

Wittgenstein

The fourth and most modern of the fideist philosophers I will mention is Ludwig

Wittgenstein. His position grew out of

his larger claims about language, how it works and what one can and cannot do

with it.

One of his most influential

philosophical works which he completed early in his career was the Tractatus.[9] The major theme of the Tractatus

was an examination of propositions which

express facts about the world.

This is the limit of and the function of meaningful propositions. But even here he seems to agree with 18th

Century philosopher, David Hume, that the mere rational appreciation of facts

is itself, value neutral. The facts are

just the facts and the propositions in themselves are entirely devoid of value.

This is the proper domain of scientific language. Everything else, everything about which we

care, everything that might render the world meaningful, must reside elsewhere.

(See Tractatus 6.4)

So, a properly logical language, Wittgenstein

held, deals only with what is true/factual. Aesthetic judgments about what is beautiful

and ethical judgments about what is good cannot even be expressed within the

logical language, since they transcend what can be “pictured” in thought. They

aren't facts. The achievement of a wholly satisfactory description of the way

things are would leave unanswered (but also unaskable)

all of the most significant questions with which traditional philosophy was

concerned. (Tractatus 6.5)

At the end of the Tractatus Wittgenstein famously

states:

"Whereof One

Cannot Speak, Thereof One Must Be Silent." Tractatus

7)

How this quote is to be interpreted is a

matter of debate among Wittgenstein scholars. Some claim that he believes that math

and science exhausts the domain of meaningful discourse and inquiry,

effectively dismissing anything falling outside. This of course was the view of the Logical

Positivists of this same period. Others argue

that, even here, he thought the most important features of human life, ethics and religion, are beyond the limits of language and

speculative philosophy. Faith, then, is

not something on which philosophy or science can pass judgement.

There are two predominant views of these

final remarks in the Tractatus:

- His

later work Philosophical

Investigations is in fact his own refutation of the position developed

in the earlier work, a rejection the former logical atomist position and

the “picture” theory of language which he in fact held when writing the Tractatus.

- Philosophical

Investigations is a confirmation

of the conclusion that he reaches in the Tractatus; namely, that the

atomist position and the picture theory of language are nonsense and must

be transcended.

Two Views of

Language:

The “picture view of language.” A proposition is a picture of reality true if

and only if it corresponds to the way the world is. Names stand for objects in the actual world.

The “game view of language.” “Language is an instrument. Its concepts are

instincts.” PI #569) There are multiple language games and which language “plays”

are appropriate depend upon which of the varying human practices one is

participating in. Language's meaning is

how it is employed per se in each context: “The question is ‘What is a

word really? is analogous to ‘What is a piece in chess?’ (PI #108).

Wittgenstein switches from the first to

the second. On the first view, what

results is something like the Logical Positivists’ limitation as to what

constitutes “meaningful” uses of language.

Metaphysical, ethical, aesthetic sentences, since they are not expressions

of empirical propositions, are really non-sensible

when examined as propositions.

However, while the mystical cannot be

spoken, it nevertheless still seemed to be of concern, perhaps of most concern,

even to the early Wittgenstein. In a

letter to the publisher Ludwig von Ficker,

Wittgenstein states

"[M]y work

consists of two parts: of the one which is here, and of everything which I have

not written. And precisely this second part is the important one. For the

Ethical is delimited from within, as it were, . . . in my book by remaining

silent about it" (qtd. Monk 178).

This would suggest that the Tractatus

might be seen as a “via negativa” of its own.

Elsewhere:

Now I

often tell myself in doubtful times: “There is no one here.” and look

around. Would that this not become something base in me!

I

think I should tell myself: “Don’t be servile in your religion!” Or try not to

be! For that is in the direction of superstition.

A

human being lives his ordinary life with the illumination of a light of which

he is not aware until it is extinguished. Once it is extinguished, life is

suddenly deprived of all value, meaning, or whatever one wants to say. One

suddenly becomes aware that mere existence—as one would like to say—is in itself still completely empty, bleak. It is

as if the sheen was wiped away from all things, everything is dead.[10]

On the picture view of language

Wittgenstein is then committed to mysticism ultimately. Ethics and God are beyond what language can

speak of sensibly.

On the game view of language, such

questions are answered by living and practice.

Life is to be lived, acted out. Religious practice is one more language

game. The content of religious “propositions” (if they can be called that) is just as

indemonstrable and cannot be defended as rational doctrinal proofs. But that is not called for in the religious

practice. That simply is not a licensed

play.

Superficial and

Depth Grammar

It is common to distinguish three main

domains of linguistic study: syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. “Grammar” is generally associated with the

first of these domains, and is taken to refer to the

study of the structure or form of languages.

But Wittgenstein departs from this convention. He further distinguishes between what he call surface grammar and depth grammar.

“In the use of words one might distinguish 'surface grammar' from 'depth

grammar'. What immediately impresses itself upon us about the use of a word is

the way it is used in the construction of sentences, the part of its use - one

might say - that can be taken in by the ear. - And now compare the depth

grammar, say of the word "to mean", with what its surface grammar

would lead us to suspect. No wonder we find it difficult to know our way about.

(PI 664:).

There is dispute about what, precisely,

he means by this distinction, but a reasonable interpretation might be

this. By surface grammar he is primarily

concerned with the syntactical role the word plan in the natural language. By depth grammar he more or

less uses this interchangeably with the terms meaning (semantics) and use

(pragmatics). For instance, he takes

questions such as "How is the word used?" and "What is the

grammar of the word?" as being the same question.

What is more, he suggests that we can

substitute the phrase "meaning of a word" for "use of a

word" and proposes that the investigation of meaning should go hand in

hand with the investigation of use. This

suggests that the later Wittgenstein‘s concept of grammar breaks with standard

use of the term, and that for him, talk of grammar pervades the different

domains of linguistic inquiry rather than being limited to any particular one

of them.

In his essay “On Certainty,” Wittgenstein

asserts that claims like “Here is a hand.” or “The world has existed for more

than five minutes.” [11] have

the appearance of empirical propositions, but that in fact they have more in

common with logical propositions. While

these may seem to say something factual about the world, and hence be open to doubt, really the function they serve in language is

to serve as a kind of framework within which empirical propositions can make

sense. In other words, we take such

propositions for granted so that we can speak about the hand or about things in

the world. These propositions aren’t

meant to be subjected to skeptical scrutiny in the regular conduct of the

language within which they occur.

Doubting them would be like treating a rook as if it were a pawn. You are violating the rules of the game in

which these sentences occur.

At one point, Wittgenstein compares

these sorts of propositions to a riverbed, which must remain in place for the

river of language to flow smoothly, and at another, he compares them to the

hinges of a door, which must remain fixed for the door of language to serve any

purpose. The key, then, is not to claim certain knowledge of propositions like

“here is a hand” but rather to recognize that these sorts of propositions lie

beyond questions of knowledge or doubt.

Practice is what determines what it makes sense to say and what to “do”

with what is said.

Wittgenstein’s 1929 Lecture on Ethics

can be considered part of a transitional position between the Tractatus and Philosophical Investigations. There he holds to the idea that language

which cannot be empirically verifiable is, in one sense, "nonsense,"

but it is also terribly serious and admirable.

So religious language takes its

meaning from religious life. Its surface

grammar looks empirical, (like “Here is a hand.”), but its deep grammar is very

different. One deploys religious

language in a religious form of life and the language is in a sense, some of

the “props” of the religious language game.

He rejects the idea the word and sentences have fixed “meanings”

irrespective to the context in which they occur or the uses to which they are

being put.

What I actually

want to say is that here too it is not a matter of the words one uses or

of what one is thinking when using them, but rather of the difference

they make at various points in life.[12]

(Emphasis added.)

http://www3.dbu.edu/mitchell/wittgensteinassessment.htm

Some Quotes from Wittgenstein

“Religious faith and superstition

are quite different. One of them results from fear and is a sort of false

science. The other is a trusting. (Culture

and Value p. 72)

"A proof of God’s existence

ought really to be something by means of which one could convince oneself that

God exists. But I think that what believers who have furnished such proofs have

wanted to do is give their ‘belief’ an intellectual analysis and foundation,

although they themselves would never have come to believe as

a result of such proofs. Perhaps one could ‘convince someone that God

exists’ by means of a certain kind of upbringing, by shaping his life in such

and such a way."

“Burning in effigy. Kissing

the picture of a loved one. This is obviously not based on a belief that it will have a

definite effect on the object which the picture represents. It aims at some satisfaction and it achieves it. Or rather, it does not aim at anything; we act in this way and

then feel satisfied”

“Queer as it sounds:

The historical accounts in the Gospels might, historically speaking, be

demonstrably false and yet belief would lose nothing by this: not, however

because it concerns 'universal truths of reason'! Rather because historical

proof (the historical proof-game) is irrelevant to belief. This

message (the Gospels) is seized on by men believingly (i.e.

lovingly). That is the certainty characterizing this particular acceptance-as-true, not something else.

“A believer's relation to these

narratives is neither the relation to historical truth

(probability), nor yet that to a theory consisting of 'truths

of reason'. (CV 32)

God is not a ‘thing’ like any

other

‘a religious belief could only be something like a

passionate commitment to a system of reference. Hence, although it’s a belief,

it’s really a way of living, or a way of assessing life. It’s passionately

seizing hold of this interpretation.’ (Culture and Value, §64)