Faith and

Irrationality; Kierkegaard

Fideism:

the

doctrine that knowledge depends on faith or revelation.

Fideism

is the epistemological position that faith is independent of reason (sometimes suggesting

that reason and faith are hostile to each other) and faith is a superior means

for arriving at particular truths.

The

word fideism comes from fides, the

Latin word for faith, and literally means "faith-ism."

Philosophers

have responded in various ways to the place of faith and reason in determining

the truth of metaphysical ideas, morality, and religious beliefs. A fideist suggests that reason plays little or no role in

religious matters and even is antithetical to true religious sentiment. The four most well know theists philosophers

who espoused fideism are Blaise Pascal, Soren Kierkegaard, William James, and

Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Sometimes

the label fideism is applied in a negative sense by their opponents. To evidentialists

like William Clifford, Fideism is irrational (in a bad way) and immoral. Someone like Daniel Dennett would say it is

intellectually irresponsible at a minimum.

There

are a number of different forms of fideism.

According to Pascal:

The God of Christians does not consist of a

God who is simply the author of mathematical truths and the order of the

elements: that is the job of the pagans and Epicureans. He does not consist

simply of a God who exerts his providence over the lives and property of people

in order to grant a happy span of years to those who worship him: that is the

allocation of the Jews. But the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of

Jacob, the God of the Christians is a God of love and consolation; he is a God

who fills the souls and hearts of those he possesses; he is a God who makes

them inwardly aware of their wretchedness and his infinite mercy, who unites

with them in the depths of their soul, who makes them incapable of any other

end but himself. (PENSEES, 172)[1]

Around

two centuries later, Soren Kierkegaard similarly contrasted the God of

Christian faith with the God of the philosophers, in particular that of Hegel

and some of his Danish followers. The “God” of Hegelian philosophy, Kierkegaard

thought, at best provides a solution to a purely abstract problem. What Kierkegaard sought (and Hegel does not

provide) is the God of immediate personal significance. This is discovered/

necessitated as the only adequate resolution of the problem of personal human

existence.

William

James is another who thought that philosophical and theological arguments could

not be the origin of any significant religious belief. At best it could provide

some logical clarification of knowledge or beliefs gained from religious

experience. But direct religious experience is the source of true religious

sentiment and belief, not rational argument.

All these intellectual operations of theology

and philosophy presuppose immediate religious experience as their subject

matter. They are interpretive and

inductive operations, operations after the fact, consequent upon religious

feeling, not coordinate with it, not independent of what is ascertains.

The intellectualism in religion which I wish

to discredit pretends to be something altogether different from this. It assumes to construct religious objects out

of the resources of logical reason alone, or of logical reason drawing rigorous

inference from non-subjective facts. It calls its conclusions dogmatic

theology, or philosophy of the absolute, as the case may be. (VRE 433)

James

probably had the philosophies of Hegel and Bradley in mind. Their conclusions have been criticized as

largely meaningless except as edifying verbiage.

Kierkegaard

is critical of Hegelian philosophy for other reasons as well. In the philosophical system advance by Hegel,

the individual was of little or no importance.

The only significance the individual achieved was as an aspect of

constantly unfolding Absolute Spirit.

However, this anonymizing of the individual mutes the individual, her

struggles, choices, uniquely lived life, her very existence-as-existing. Further, while Hegel had thought that all

apparent contradictions (the thesis with its antithesis) are subsumed into an

evolving dynamic history, into a synthesis, Kierkegaard, the individual, and on

behalf of the individual, wanted to testify to the struggle of choice (Either/ or) which is unavoidable in a lived

life.

John

Macmurray explains careful Kierkegaard (and perhaps

other fideists) as follows:

The Danish eccentric, Kierkegaard, discovered

that the Hegelian philosophy was ludicrously incapable of solving - even,

indeed, of formulating the problem of “the existing individual.” If we apply

the Hegel’s logic to the data of personal reality, we produce, he showed, “a

dialectic without synthesis’: for the process of the personal life generates a

tension of opposites which can be resolved, not by reconciliation but only by a

choice between them, and for this choice no rational ground can be

discovered. He concluded that we must

abandon Philosophy for religion. (The Self 36)

Faith and the Story

of Abraham

Every

philosopher so far has presumed that what we want to believe all and only what

is rational. Anselm, Aquinas, Pascal, Clifford, James,

Kant, Advocates of the Problem of Evil.

Soren Kierkegaard (from Denmark) says belief in God is not, not cannot

be rational, but that doesn’t make it a bad thing.

- Religious faith is not nor can it ever be a

“rational” matter

- Kierkegaard referred to himself as an anti‑philosopher,

- Brooded over the nature of “faith;” performs a

sort-of conceptual analysis.

The

time and country he lived in were largely Christian. His fellow Dane he regarded as complacent in

their religious belief; religious belief amounted to sort of a daily

passionless habit. But was this real

Faith? What is real faith about?

Kierkegaard claimed that complacent, thoughtless, routine is not real faith. Kierkegaard’s philosophy originate with him

brooding over these questions, questions regarding the real nature of personal

faith.

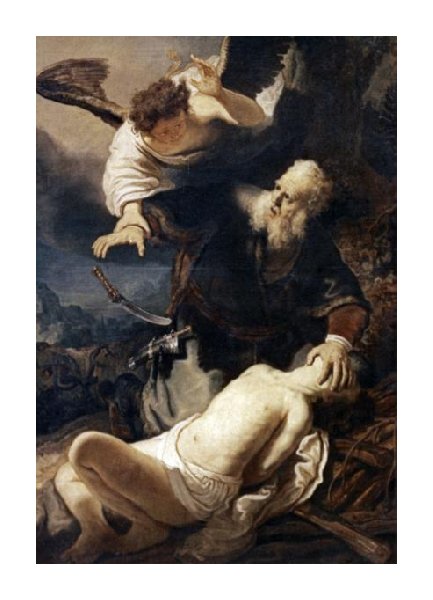

The Abraham

Story

Abraham

considered the “father of faith” but those is the Abrahamic religions because

had a special relationship of God. Kierkegaard examines the story of Abraham to

discover what “religious faith” is since those who use the word often point to

this story as illustrative.

http://kingjbible.com/genesis/22.htm

1 And it came to

pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him,

Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am. 2 And he said, Take now thy son, thine

only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and

offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will

tell thee of. 3 And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass,

and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood

for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had

told him. 4 Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw the place

afar off. 5 And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass;

and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you. 6 And

Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son;

and he took the fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them

together. 7 And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and

he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but

where is the lamb for a burnt offering? 8 And Abraham said, My son, God will

provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together.

9 And they came to

the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid

the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the

wood. 10 And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his

son. 11 And the angel of the LORD called unto him out of heaven, and said,

Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I. 12 And he said, Lay not thine hand

upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou

fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me. 13

And Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught

in a thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him

up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son. 14 And Abraham called the name

of that place Jehovahjireh: as it is said to this day, In the mount of the LORD

it shall be seen.

Story of Abraham

So

we see that Abraham had son, Isaac whom he loved deeply. How does/should Abraham respond to God's

apparent command that Abraham take his son out and kill him? This is a crisis of faith. Further, Kierkegaard cautions us that it is a

mistake to think Abraham merely had to decide whether to do God’s will or

not. Rather, he had to decide what that

“voice in the night” meant. He must interpret the event, give it its

meaning. And various interpretations are

open to Abraham. He must choose to interpret

and that choice cannot be “rational” or based on evidence since it is the

making of the choice, the interpretation itself, which will determine WHAT the

“evidence” is evidence of.

"Voice"

in the night might be evidence of:

1.

God’s sincere desire?

2.

God’s test of Abraham’s morality?

3.

A demonic trick?

4.

Abraham’s own insanity?

Abraham's

choice (and only his choice) determines what this voice is evidence of. He MUST choose; his personal choice is the

only way to resolve the issue.

After

his choice of interpretation he must further decide how he will respond to the

(newly created) “evidence.”

Kierkegaard

is pointing out that, contrary to what we might initially suppose, we do not

base our choices on evidence, at least not the really important ones, but

rather it’s the other way around; we base evidence on choices. The voice is not evidence of anything until

it is given an interpretation. What

interpretation it is given is a free (undetermined) choice for which we are totally responsible. Further, we can get no rational assistance in

making these choices but the most important things in our live rest on them.

Nothing is “reasonable” (or

unreasonable for that matter) until after one makes the choices. This is why we must abandon philosophy for

faith.

This

is why Kierkegaard is considered the founder of Existentialism.

Existentialism

– school of thought founded by Kierkegaard which stresses individual personal

choice and responsibility; major and minor decisions made in life are your

choices; free to choose whatever you will; complete freedom but therefore total

responsibility rest with the individual.

They are matters of creative self-definition.

Further

still, these free existential choices are the most important choices in

life. Abraham's world, everything

important to him (his son, his relationship with God, his progeny) was riding

on this choice. And he is compelled to

choose. As Sartre would later say, we

are condemned to be free.

He

must therefore make a Leap of Faith

Leap of Faith:

a passionate commitment that one makes without regard to reason, evidence or

argument.

This

is precisely what Abraham does, according to Kierkegaard, and this is why he is

a hero of faith. This then is the nature

of true faith. The recognition of the

futility of reason and the necessity for personal unaided choice.

Why

then is he, Kierkegaard, a Christian?

The only honest answer anyone can give is because he chooses to be one- NOT

because of supposed evidence for or against.

But the choices do not stop there.

So he’s decided to be a Christian.

What does that MEAN? He must choose what being a Christian

means. Being a Christian might mean

killing your innocent child. One is not

“done” choosing when one makes a choice to be “X” because, while “X” names a

“kind” you are an INDIVIDUAL. You are

THIS X, and only you decide what being “this X” means. This is the case for any role: father,

mother, son, citizen, Christian, etc. None of these name “fixed essences” or if

they do, then you are not essentially any of them. You are them by choice. Even assigned feature about you mean nothing

until you choose for them a meaning. For

instance I am 5’ 7’’. But what does that

mean? I am not “generic” 5’7’; I am THIS

5’7” and I choose for myself what that

means. What role that plays in my life.

Should

you be a Christian? Keirkegaard would

ask, “Why are you asking me?” You have

to choose what you will be; this is

what makes it an “existential”

choice. You create yourself through

such leaps and choices.

To

further demonstrate the disconnect between faith and reason, Kierkegaard notes

that sometimes Christianity requires the embracing of two things that are

mutually impossible, irrational. For

instance, Abraham believed that he would kill Isaac AND that through Isaac,

Abraham would go on to have many descendants.

Kierkegaard

claims that religious faith is of the same character as are any of the really

important decisions we make in life.

They are not made on evidence; they are choices. Religious faith is a non‑rational

commitment irrespective of evidence, argument, or reason. We believe in God (or believe in NO God)

simply because we choose to; such beliefs can't be based on evidence; what you

are looking at doesn't have a meaning until after you make a choice. (Note this is not unlike the choice to live a

moral or immoral life; this is not evidence based. We can always rationalize after the fact, but

the reality is that we simply choose to be who we choose to be.)

Kierkegaard

says ‑ Religious belief is a leap of faith; a passionate commitment that

we make regardless of evidence or argument; regardless of Theist or Atheist;

choice precedes evidence; choice makes evidence.

Finally,

we must not imagine that once an existential choice is made, it is over. Each day requires we make ourselves

anew. For Kierkegaard, the Christian

life calls for constant reaffirmation.

Everyday it is a struggle to be a Christian. Alternatively, just because I did not cheat

the last time I had an opportunity does not mean that is the choice I am

compelled to make today. Since every day

we are free to define ourselves, everyday we are compelled to answer for

ourselves “Who am I?”

As

illustrations of the sort of thing he has in mind, consider tow cases; The "Bloody Glove" in the O.J.

Simpson murder case and the Shroud of Turin.

In

the O.J. Simpson murder case there was a key bit of "evidence" was a

pair of bloody gloves:

Bloody Gloves:

One dark, cashmere-lined Aris Light leather glove, size

extra large, was found at the murder scene, another behind Simpson's guest

house, near where Brian "Kato'' Kaelin heard bumps in the night. Mrs.

Simpson bought O. J. Simpson two pair of such gloves in 1990. DNA tests showed

blood on glove found on Simpson's property appeared to contain genetic markers

of O. J. Simpson and both victims; a long strand of blond hair similar to Ms.

Simpson's also was found on that glove.

Prosecution: Simpson lost the left glove at his

ex-wife's home during the struggle and, in a rush, inadvertently dropped the

right glove while trying to hide it; they explained that evidence gloves didn't

fit Simpson in a courtroom demonstration because the gloves shrunk from being

soaked in blood and Simpson had rubber gloves on underneath.

Defense: glove behind guest house was planted by

Detective Mark Fuhrman, a racist cop trying to frame Simpson; blood on glove

may have been planted by police; undersocres that the evidence gloves didn't

even fit O.J. Simpson; hair analysis isn't sophisticated enough to be trusted.

What

were the gloves "evidence" of?

Well, from a Kierkegaardian point of view- nothing until you choose to

believe. If you choose to believe he is

innocent, they are evidence of a corrupt police plant and frame job. If you choose to believe he is guilty, they

become evidence of his presence at the scene and participation in the

murder. But again, it would be a mistake

to assume the evidence determines what it rational to believe; it is what you

choose to believe that will determine what "evidence" there is.

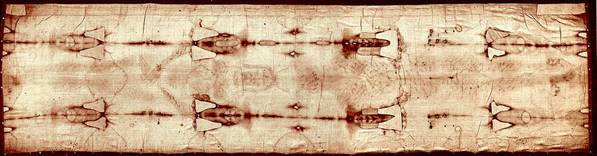

The Shroud of Turin

The

Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth bearing the image of a man who appears to have

sustained wounds and to have died in a manner consistent with the story of the

crucifixion of Jesus. It is housed in

the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. Historical records only trace a provenance to

about the 1300's. At that time, numerous

"holy relics" and "shrouds" were produced but whereas these

others, upon closer inspection, could clearly be seen to be fakes, the Shroud

of Turin is intriguing because it was not an obvious fake. In fact, the image on the shroud could not be

made out very well until it was photographed (circa 1930) and the negative was

looked at. When the values are reversed,

the image is much more recognizable and detailed. Many argued that it was unreasonable to

imagine a forger anticipating the invention of Photography. Other historical accuracies lead many to believe

it to be genuine, that is, to be the cloth that covered Jesus of Nazareth when

he was placed in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. Some even suggested that this image was

recorded on its fibers at the time of his miraculous resurrection.

In 1988, for the first time, the Catholic Church

permitted radiocarbon dating of the shroud

by three independent teams of scientists. Each concluded that that the shroud was made

during the Middle Ages, approximately 1300 years after Jesus lived. Almost immediately, spokesmen on behalf of

the Roman Catholic Church acknowledged the results, acquiesced to the judgement

of science, expressed their disappointment and pledged, nevertheless, the take

care of the shroud as so many did find it inspiriting nevertheless.

Sometime a later a group of Protestant theologians and

scientists issued their own statement.

They criticized what they thought was an unnecessary and overly hasty

acceptance of this scientific evidence about the age of the shroud. They argued that if there were a resurrection

(as the Catholic Church and other Christians are supposed to believe) and if

there were at that time a great release of electromagnetic radiation or the

like, (as may seem plausible) then we ought to expect that the radiocarbon

dating process is give us the wrong, much younger, date.

So,

radiocarbon dating suggests that the shroud is only approximately 700 year

old. What is that evidence of? Does it prove that the shroud is a fake. Or

does it prove that it is genuine and further is evidence of the resurrection of

Christ? Kierkegaard might claim,

either. It depends on you. Both require your leap of faith.

Camus' Myth of Sisyphus (Taken from my notes on suicide)

One

reason some people think that suicide is wrong is because the noble thing for

human to do is to persevere, even in the face of meaningless pointless

suffering and struggle. (Existentialism/ Camus Essay "The Myth of

Sisyphus")

Existentialists

believe that we are totally free in all are actions and that we are totally

responsible for all our actions. When you try to push your freedom off onto

others, this bugs existentialists. For example, when a salesman convinces you

to buy something overpriced and then you blame him when you found a better deal

later ("He talked me into it… etc.") , existentialists will remind

you that you chose to listen to him and it’s your own fault. You can’t pretend

it wasn’t your choice. Now, there are

consequences, and you may not like those consequences, but it was still your

choice. Further, there are some things that are out of your control, such as

your height, but what these things mean to you is under your control. You assign the meaning to these things and it

is something you choose. There is a sense in which you DO chose to be that

height because chose what being that height means. You live exactly the life you choose to live.

Soren

Kierkegaard, founder of Christian Existentialism. He comes to existentialism as

a way to understand faith. He understands faith as a choice someone makes.

There is this unknown and we can respond to the unknown by saying “God” or “not

God”, but in either case we’re making a choice and in either case it is a

choice undetermined by evidence.

Later

existentialists add to this view that no one’s "keeping score" (There

is no God.) and we’re NOT immortal. Our death is our total annihilation. All

these choices for which we are responsible and with which we struggle, don’t

really matter in the long run. We’ll

eventually die and will eventually be forgotten. Our lives only have the

significance that we attribute to them and for as long as we do it. Some people

jumped the gun and thought well, then I should just kill myself, since there’s

no point to my life. But Albert Camus points out that that is merely another

meaningless choice. So, existentialists

think we shouldn’t kill ourselves. Our lives may be full of pointless, arduous

struggles, but the noble thing is to struggle on, even in the face of pointless

struggle. It is what we make of our

selves (self-creation) in the struggle that is important. That is the source of our nobility and ending

our lives ends the possibility to "be."

To

illustrate his point, Camus retells the story of Sisyphus. Sisyphus was an ancient Greek king. To test the love of his wife, before Sisyphus

died, he forbade her from burring his body.

(The thinking being is that if she really loved him, she could not obey

this command.) However, his wife did

obey and Sisyphus, annoyed, asked for permission to return to Corinth to yell

at her. He was granted permission only

on the condition that he promise to return, which he did promise. Once back on the upper world though, he found

he did not want to go back to the land of the dead. He refused though Hades sent several

massagers. Eventually he had to be dragged back kicking and screaming to the

underworld by Hermes. As a punishment

for his disobedience and hubris Sisyphus was compelled to roll a huge rock up a

steep hill, but before he could reach the top of the hill, the rock would

always roll back down again, forcing him to begin again. Now for the Greeks, this was Hell, to be tied

to unending, meaningless struggled, to be compelled to labor even when one

knows that one's labor will amount to nothing.

But

for Camus, Sisyphus is our hero and emblematic of the humans condition. We are all tied to arduous struggle,

meaningless choices from which we cannot escape. And Why?

What was Sisyphus' “crime?” To

be. To live. But if this is the price of existence says

Camus, than it is worth it. For our

nobility arises in what we make of ourselves in the struggle. The struggle with the absurd is result of our

freedom and the source of our dignity.

We must imagine Sisyphus happy, he concludes, for "The struggle

towards the heights itself is enough to fill a man's heart."[2]