Science, Biology and Teleology:

Tell them about

1. Aristotle

2. The Copernican Revolution

3. The advent of Modern Philosophy and

4. Cartesian mechanism.

And Descartes’ doll…

Since the eighteenth century, there has been in circulation a curious story about Descartes. It is said that in later life he was always accompanied in his travels by a mechanical life-sized female doll which, we are told by one source, he himself had constructed 'to show that animals are only machines and have no souls. He had named the doll after his daughter, Francine (1635 - 1640), who had died of scarlet fever as age 5.

Descartes and the doll were evidently inseparable, and he is said to have slept with her encased in a trunk at his side. Once, during a crossing over the Holland Sea some time in the early 1640s, while Descartes was sleeping, the captain of the ship, suspicious about the contents of the trunk, stole into the cabin and opened it. To his horror, he discovered the mechanical monstrosity, dragged her from the trunk and across the decks, and finally managed to throw her into the water.

We are not told whether she put up a struggle.

Teleology came under attack when early modern scientists —still called “natural philosophers” at the time— began searching for physical and material explanations, for eternal physical laws that regulate falling bodies and the motion of planets. Modern philosophy and modern science can be characterized as the rejection of the Aristotelian “Final Causality” as model of “causation” and as an explanatory resource for science.

Thereafter, there ensued a Vitalist/Mechanist debate.

The Vitalists-Mechanist controversy of the 18th and 19th centuries is often portrayed in terms of the progressive mechanists (the good guys) being opposed by the reactionary vitalists (the bad guys). As far as the mechanists were concerned, the reductive/ mechanist picture of the natural world is basically correct. The mechanists were charting a new path, one that would prove immensely productive in generating biological knowledge.

Vitalism: the doctrine that “living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical/ non-mechanistic element or are governed by principles different than those mechanistic principles governing inanimate things.

By contrast, the mechanists were carrying out the program that Descartes had envisaged, but only pursued speculatively. They sought to show how many (all) of the phenomena exhibited in living organisms could be explained in terms of the component parts of those organisms carrying out, component operations in much the same manner as is the case in human-engineered machines.

The vitalists were critics of this view who pointed to what they regarded as the limitations of the mechanistic accounts of their day. The limitations were not just incidental but went to the core of the mechanistic project as it was pursued. They charged that mechanist accounts lacked the resources to account for some of the most fundamental features of living organisms. Unlike the human-engineered machines that provide the model for mechanistic accounts, organisms build, sustain, and repair themselves. (i.e. The exhibit self-directed goal pursuing behavior.) In doing this they are not just reactive—they are endogenously active. That is, they behave is ways explained by/ caused by factors inside the organism or system.

Endogenous: caused by factors inside the organism or system. (Inner directedness-Me)

NB: It is worth noting that Vitalist resistance to mechanistic reductive account of life and mind stand behind other 19th century movements such as German Idealism, American Transcendentalism and British Absolute Idealism.

William James (1842 – 1910), in his Varieties of Religious Experience, and his psychology more generally, is likewise critical of mechanistic accounts of mind and these approaches to mental health.

So how much of a problem does the seemingly “internal directedness” of biological organisms present for the biological mechanists?

Three Questions Arise:

· Can purely mechanist systems exhibit such inner directedness?

· And if so, how would/did/do such complex mechanistic systems arise?

· Can such processes occur in “blind” nature?

Teleology and Function

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964)

[in the `30s] can be found remarking,

“Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her, but he's unwilling to be seen with her in public.”[1]

David Hull (1982)

“Today the mistress has become a lawfully wedded wife. Biologists no longer feel obligated to apologize for their use of teleological language; they flaunt it. The only concession which they make to its disreputable past is to rename it ‘teleonomy’.”

Teleonomy: the quality of apparent purposefulness and of goal-directedness of structures and functions in living organisms, which is in fact brought about by natural (i.e. presumably thoroughly mechanistic) laws.

This, in truth, is not far from Kant’s account of teleology. The appearance of teleology results from an ordering function of human cognition on its experience of living realities, but should not be taken more literally than that.

So the appearance of teleology is not only acknowledged, but seen to be useful/ valuable in scientific research. But what does it amount to and how does it arise?

Nevertheless, for the sake of what?

Aristotle:

"Democritus, however, neglecting the final cause, reduces to necessity all the operations of nature. Now they are necessary, it is true, but yet they are for a final cause and for the sake of what is best in each case. Thus nothing prevents the teeth from being formed and being shed in this way; but it is not on account of these causes but on account of the end; these are causes in the sense of being the moving and efficient instruments and the material.

"Democritus, however, neglecting the final cause, reduces to necessity all the operations of nature. Now they are necessary, it is true, but yet they are for a final cause and for the sake of what is best in each case.

"Thus, nothing prevents the teeth from being formed and being shed in this way (i.e. efficient and material causality); but it is not on account of these causes, but on account of the end; these are causes in the sense of being the moving and efficient instruments and the material.

". …to say that necessity is the cause is much as if we should think that the water has been drawn off from a dropsical patient on account of the lancet alone, not on account of health, for the sake of which the lancet made the incision."

Aristotle, Generation of Animals V.8, 789a8-b15

Doesn’t Aristotle Still have a Point?

We might know, for instance, that…

“The plasma coagulation system in mammalian blood consists of a cascade of enzyme activation events in which serine proteases activate the proteins (proenzymes and procofactors) in the next step of the cascade via limited proteolysis.

The ultimate outcome is the polymerization of fibrin and the activation of platelets, leading to a blood clot.

But we are still none the wiser as to WHY (i.e. for the sake of what) the blood clots. (i.e. to keep you from bleeding to death.)

Not everything THAT a thing does in relevant to the question as to why it does that thing? Not everything that an organ accomplishes is its function. (The heart also goes ba-bump ba-bump, but that’s not its function.) Further, knowing that some activity and which activity is the function of an organ, or a system seem really important scientific knowledge.

Now, Plato would tell us that everything was created by demiurgos. Since demiurgos (god) created everything for a reason, everything is at its best:

“This ordered world is of mixed birth; it is the offspring of a union of Necessity and Intellect. Intellect prevailed over Necessity by persuading it to direct most of the things that come to be toward what is best, and the result of this subjugation of Necessity to wise persuasion was the initial formation of this universe (Timaeus, 48a trans by Zeyl).”

Aristotle posits teleology as fundamental:

· Like moves to like: For instance, a stone falls toward the center of earth because they are both made up of same essential ingredients.

· Development of organisms from birth to adulthood is guided by an intrinsic purpose. The adult organism is the purpose of development.

· Functional parts of organisms exist because of their benefits to their possessors.

· Pure chance cannot explain the order we observe in organic and inorganic worlds.

Note: he wasn’t just making this up. He thought this was evident to the senses. Thus we are left again to ask: “Is it even Possible that Mechanistic Systems Exhibit self-directed or self-regulating Behavior?”

Naturalizing Teleology

To provide a mechanistic/naturalized account of apparent teleology, we would need to ground (or reduce) teleological systems in natural mechanistic phenomena. To do this we must show under what conditions a mechanical system can exhibit self-regulating and/or goal-directed behavior

Two main naturalizing strategies: teleonomic features arise from

1. Negative Feedback (and Cybernetics: a mechanistic program directing activity)

Examples of self-regulating mechanistic systems are just the sort of ting we are looking for the gain insight on what is required.

2. Natural Selection preserving “useful” functions which arise mechanistically.

Negative Feedback

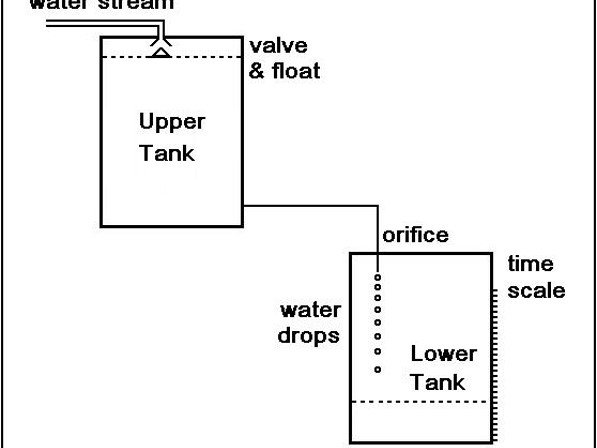

The first known example of mechanical negative feedback mechanisms: Water clock designed by Ktsebios.

Water drops falling from orifice of an upper tank accumulate in the lower tank and the increasing water level indicates how much time has expired. However, the accuracy of the clock requires a constant flow rate of water from the upper tank into the lower-level container. The flow would fluctuate if the water pressure in the upper tank fluctuates (i.e. it diminishes as the tank empties).

To solve the problem, one must keep the upper-tank water level constant. He designed a float that would start or stop the inflow from the water supply to maintain a constant level. The a valve would open as the water level dropped and, once the water level returned to the optimal level, would close, preventing the upper tank from getting too full.

This is the first documented use of the concept of a feedback mechanism to create a self-regulating mechanical system.

Water Clock

During the industrialization of the 18th and 19th centuries, we sees a proliferation of negative feedbacks mechanisms in self-regulating mechanistic systems.

James Watt (1736 -1891)

· Scottish Inventor

· Faced a serious practical challenge – How to control the speed of the steam engine so that all appliances would run at the same rate despite different number being on line at a time

· Devised an elegant mechanism for feedback control

During WW II, a challenge arose: how to control gun fire targeting aircraft.

Solutions: Use feedback from the first shot to correct the next.

The same principles are exploited in heat seeking missiles and beyond. (Keep adjusting and firing until the heat signature is no more.)

Cybernetics

Recognizing the commonality between control of anti-aircraft fire and control in biological system, Norbert Wiener created an interdisciplinary movement: Cybernetics

Cybernetics—from the Greek for Helmsperson

Cybernetics is a wide-ranging field concerned with regulatory and purposive systems. The core concept of cybernetics is circular causality or feedback—where the observed outcomes of actions are taken as inputs for further action in ways that support the pursuit and maintenance of particular conditions, or their disruption. Cybernetics is named after an example of circular causality, that of steering a ship, where the helmsperson maintains a steady course in a changing environment by adjusting their steering in continual response to the effect it is observed as having.

Other examples of circular causal feedback include: technological devices such as thermostats (where the action of a heater responds to measured changes in temperature, regulating the temperature of the room within a set range).

Cybernetics is concerned with feedback processes which amount to “steering” however they are embodied including in various systems:

· Ecological

· Technological

· Biological

· Cognitive

· Social

The cybernetics of the 1940s and 50s is the precursor to fields such as computing, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, complexity science, and robotics among others. As cybernetics developed, it became broader in scope to include work in domains such as design, family therapy, management and organization, pedagogy, sociology, and the creative arts. At the same time, questions arising from circular causality have been explored in relation to the philosophy of science, ethics, and constructivist approaches, while cybernetics has also been associated with counter-cultural movements. Contemporary cybernetics thus varies widely in scope and focus, with cyberneticians variously adopting and combining technical, scientific, philosophical, creative, and critical approaches.

We see similarly structure systems in nature:

· Biochemical systems: products of reactions feedback to slow reactions earlier in the pathway. (Like the clock, disadvantageous traits act to mechanically slow reproduction of the genome.)

· Physiological systems: when the variable deviates from norm (e.g. homeostasis/ temperature), processes are initiated to restore it to normal (like a coiled thermostat).

· Motor systems: when action misses the mark, change to guide it to the target. (Shark pursuing its pray/ Roomba’s bumping into the wall/ Heat seating antimissile defenses.)

Homeostasis in Biological Systems

Walter Bradford Cannon, M.D. (1871 – 1945) posited “homeostasis.” He points to the generality of negative feedback mechanisms in biological systems to maintain an optimum state of affairs.

But The Spookiness of Teleology

Recall that, for Aristotle, natural phenomena were teleological and must be viewed this way to be properly understood. Events happened/ biological features are arranged in order to produce results. This is to answer the “for the sake of what?” question. These results explain the events even through they come after the events –

“Nature adapts the organ to the function, and not the function to the organ” (De partib. animal., IV, xii, 694b; 13)

Thus, Aristotelian (genuine) teleology seems to involve backwards causation— the later effects (function) being the cause of the process that produces the effect.

The Seeming Insufficiency of Negative Feedback Alone

to Explain Teleonomy

But… do we not again face the problem of backward causality? Humanly designed negative feedback systems all involve a designer. The designer imposes the goal on the system. So it was not the effects themselves, but the concept of the desired effect in the mind of the designer which is the efficient cause of the system features, which in turn is thew efficient cause of the effects.

But who so arranged the parts of a biological system so that it would reach the target? Where is the designer of biological systems? How did the organism become so organized that it could compensate for deviations? There could only be prior planning for biological effects if one is a Creationist. Inddes this is precisely what motivated William Paley’s (1743 - 1805) Design Argument.

However, the increasingly non-theistic scientific revolution seemed to remove this explanation for the evident teleonomy. Events happened solely because of prior mechanistic causes (efficient causation… sort of).

Teleology—Hard to Kill

Nevertheless, “teleological talk” lives on in the language of functions in biology

· “The heart’s function is to pump the blood.”

William Harvey “On the Motion of the Heart and Blood" 1628

· “The kidney’s function is to filter and remove waste.”

· “The function of the ribosome is to synthesize proteins.”

This is most evident when determining is malfunctioning. (As in medicine or ecology)

Evolutionary Biologist Ernst Walter Mayr ( July 5, 1904 – February 3, 2005) on Teleology

“Consider the following statement: `The Wood Thrush migrates in the fall into warmer countries in order to escape the inclemency of the weather and the food shortages of the northern climates'. If we replace the words ‘in order to’ by ‘and thereby’, we leave the important question unanswered as to why the Wood Thrush migrates.

“The teleonomic form of the statement implies that the goal-directed migratory activity is governed by a program. By omitting this important message the translated sentence is greatly impoverished as far as information content is concerned, without gaining in causal strength.” Mayr (1974)

Nevertheless, physics and chemistry seem to be essentially NON-teleological. If biology is essentially teleological, then there is an irreducible disunity to science.

Enter: Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882)

He replaced teleological explanations with physical explanations in terms of what he called “natural selection.” According to some, Darwin rephrased teleology from an “a priori drive” to an “a posteriori result.”

Evolution as a theory long predate Darwin. Darwin's unique contribution is that he proposes the mechanism of evolution as Natural Selection.

Natural Selection:

1. Overpopulation leads to competition.

2. Competition plus variation (via random genetic mutation) leads to differential survival.

(i.e. Some characteristics will be advantageous.)

3. Differential survival leads to differential reproduction.

4. Differential reproductions plus genetic inheritance leads to evolution.

There is a geometric increase in population so advantageous traits spread quickly through-out the population.

If successful, it is unnecessary to say, “The purpose of the heart is to pump blood.” It is more accurate (and scientific) to say, organisms which developed circulatory systems had competitive evolutionary advantages and thus differentially reproduced. And thus, teleological descriptions can be rephrased away.

Darwin in fact had high regard for Paley and took the design-like features of the world quite seriously. However, he goes on to posit a “Blind Watchmaker[2].” Biological organisms are complex systems that are highly adaptive (functional) in their environments. Darwin offers a mechanistic explanation for traits that had seemed to require design.

For the Darwinian, then, the “function” of a trait is nothing other than the effect of that trait on which natural selection operated (unenlightened trial and error among randomly generated mutations) that which caused ancestors with the trait to reproduce more successfully.

· Does natural selection remove the last vestige of teleology from science?

· Does natural selection license teleological discourse in biology?

The Etiological Account (Origins)

Larry Wright “Functions” 1973[3]

Wright: Functions as Explanatory

“Merely saying of something, X, that it has a certain function, is to offer an important kind of explanation of X.”

Wright’s Distinction Between a Trait’s Function and Other Effects

“Very likely the central distinction of this analysis is that between the function of something and other things it does which are not its function (or one of its functions). . . . The function of the heart is pumping blood, not producing a thumping noise or making wiggly lines on electrocardiograms, which are also things, it does. This is sometimes put as the distinction between a function, and something done merely ‘by accident’.” (Wright, p. 141)

The heart beats in order to circulate blood.

To ask “what is the function of X?” is comparable to asking “Why do C’s have X’s (or do X)?” The sought for explanation concerns how X came to be a feature of C’s — It suggests that it came to be because of its function. But remember the challenge: the function is realized only after X becomes the feature of C.

Question: How could what comes later (evolutionary advantage) explain what came earlier (the acquisition of the behavioral trait in the first place)?

Answer: If an organ has been naturally differentially selected-for by virtue of something it does, then we can say that the “reason” (mechanistic) the organ is there is that it did/does that something.

But this is at once to give the efficient cause of the trait AND explain its teleonomic appearance.

Hence we can say:

· Animals have kidneys because they eliminate metabolic wastes from the bloodstream.

· Porcupines have quills because they protect them from predatory enemies.

· Plants have chlorophyll because chlorophyll enables plants to accomplish photosynthesis.

· The heart beats because its beating pumps blood.

“The function of X is Z.” means one can tell this mechanistic story about the naturally differentially selected-for history of X relative to X preforming Z.

1. “X is there because it does (did) Z.” AND

2. Z is a consequence (or result) of X's being there

Thus, a two-part thesis:

1) We have hearts (mechanistically) because and action they performed which is “what hearts are for” (and now identify as its function).

Hearts are for blood circulation, not the production of a pulse, so hearts are there--animals have them--because their function is to circulate the blood.

2) #1 is explained by natural selection. Further, traits spread through populations because of their functions.

Challenges for the Etiological Account

The function of X is Z means

1) X is there because it does (did) Z

2) Z is a consequence (or result) of X's being naturally differentially selected-for.

But this account leads to misattributions of function:

Counterexample: The Mexican Cavefish[4]

On this account, the function of cavefish eyes is to provide sight/ visual information, to the organism, this despite the fact they actually don’t see.

Cavefish have (remnants) of eyes. What is their function? It was originally selected for sight. That’s why cavefish have eyes in a mechanistic way. Nevertheless, it seems a mistake to say that this is (still) their function. Similarly, what is the function of the human appendix? Darwin notes that it was used by other primates to digest leaves – Is that its function in us?

An Alternative to the Etiological Interpretation of

Function

Robert C. Cummins

In his article “Neo-teleology” is critical of the two part Etiological Interpretation of Function that, e.g., (i) we have hearts because of what hearts are for: Hearts are for blood circulation, not the production of a pulse, so hearts are there--animals have them--because their function is to circulate the blood, and (ii) that (i) is explained by natural selection: traits spread through populations because of their functions. He argues that the presence of a biological trait or structure is NOT explained by appeal to its function (a function) alone.

He challenges the principle underlying etiological account, viz.:

“(A) The point of functional characterization in science is to explain the presence of the item (organ, mechanism, process or whatever) that is functionally characterized” and “(B) For something to perform its function is for it to have certain effects on a containing system, which effects contribute to the performance of some activity of, or the maintenance of some condition in that containing system.”[5]

He insists we locate function of the broader contexts. Essentially, he claims we must explain a natural function as a relation between parts and wholes.

Relocating the Explanatory Role of Functions

As he sees it, the problem is that most functional items are neither necessary nor sufficient for realizing the salutary function. For one thing, other items could serve the same functions (thus not necessary) and the realization of the function requires more than the functional items alone (thus not sufficient). So, the occurrence of the functional items is NOT explained merely by citing the function of the functional items.

Cummins suggests instead something like: “The heartbeat in vertebrates has the function of circulating the blood through the organism.” Thus, we must refer to the role of the heart in the circulatory system. He claims that it is more plausible than the statement “Organisms with hearts differentially reproduced.” Cummings offers an explanation of the heart within the larger context of the explaining circulation itself. And this, in turn, is explained by the deferential advantages such a system provided historically/ mechanistically to the organism/ species.

That is, we start with circulation system, and identify something as having a function within that circulatory system, and thus explaining its occurrence that way. We in turn explain the advantage of the heartbeat by identifying its activity the advantageous process it facilitates. This is different than explaining the existence of the heartbeat merely in terms of its (a-historic) function.

Functions and dispositions:

“to attribute a function to something is, in part, to attribute a disposition to it. If the function of x in s to Φ, then x has a disposition to Φ in s”

Dispositions require explanation:

“if x has [disposition] d, then x is subject to a regularity in behavior special to things having d, and such a fact needs to be explained.”

The appropriate explanatory strategy:

Analytic Strategy in Biology

“The biologically significant capacities of an entire organism are explained by analyzing the organism into a number of ‘systems’—the circulatory system, the digestive system, the nervous system, etc.,— each of which has its characteristic capacities. These capacities are in turn analyzed into capacities of component organs and structures. Ideally, this strategy is pressed until pure physiology takes over, i.e., until the analyzing capacities are amenable to the subsumption strategy.”

Analytic strategy: – Analyze “d of a into a number of other dispositions d1 . . . dn, had by a or components of a such that programmed manifestation of the d1 results in or amounts to a manifestation of d”

This should seem familiar: mechanism in biology exemplifies this approach

Cummins offers a strategy for explaining functions by treating them as dispositions. Ah, but which dispositions are functions? Cummins considers a condition such as “contributes to the proper working order” of the system of which it is a part. He suggests that these in turn could be cast as “health and life” or “contributing to the survival of the species.”

Can these work to exorcise function? Does this reduce the previously teleological phenomena into phenomena that are described exclusively mechanistically?

NO!

Consider:

· “contributes to the proper working order” (Presumes function)

· “health and life” (presumes function) Health presumes well-functioning- no malfunctioning.

· “contributing to the survival of the species” such that survival of the species is a goal.

Further, this can picks out the wrong instances on some occasions, and it doesn’t explain why some features are functions while others are not. There’s a sense in which this explains too much. The same strategy is invoked for pathologies. Does the gene for schizophrenia have the function of producing schizophrenia?

Frankly this has always been my difficulty with evolutionary accounts of ethics as well. For one thing, there's probably an evolutionary explanation for why we are generous and collaborative beings, but also why we are tribal and war like. There may even be an evolutionary explanation for why we are rapists. But surely some of these behaviors are behaviors we ought to promote and others are behaviors we ought to repudiate and punish.

Evolution Can Explain Everything, and That’s a Problem

While I am not very familiar with the writings of Sam Harris, (just a smattering of YouTube clips) I believe he tries to give such an evolutionary account of objective morality. But to do this, he grounds his account in something that he refers to as “human flourishing” if I'm not mistaken. (I suppose I really should look this up.) However, the Aristotelian/ Neo-Thomist in me would like to note that one cannot develop some mind independent objective account of human flourishing apart from some mind independent objective account of human nature. Thus, final causality seems inextricably linked to formal causality. But to the best of my knowledge, Harris embraces neither.

But on a deeper level, this evolutionary mode of explanation seems unfalsifiable. If we try hard enough, and are clever and creative enough, we can probably come up with an evolutionary explanation of anything. This includes functional and non-functional behaviors. I recall reading an evolutionary account of why male birds have such distinguished bright and elaborate plumage. The theorist acknowledged that, in many cases, the bright colors and elaborate feathers make the male a more vulnerable to predators. And this fact alone would suggest it provide no evolutionary advantages. Quite the contrary and thus a feature that evolutionary theory cannot explain. Indeed, perhaps it stands as counterexamples to evolutionary theory as an explanatory resource.

However, the theorist suggested that rather than being an evolutionary disadvantage, the fact that such vulnerable males could nevertheless evade predators would have been a sign of a feature suggesting superior breeding stock, such that female birds started selecting for bright and elaborate plumage and these featured just magnified over the generations of this species. I mentioned this because it seems a rather blatant “just so” story.

Construals of Function

Talk

The etiological strategy: explain the function of something in terms of what it was selected for

· Treat it as an adaptation

· Function explained etiologically

The functional analysis strategy: explain how something is able to perform a function

· Treat functions as dispositions of things

· Decompose the disposition into sub-dispositions

A third alternative: explain the function in terms of the contribution something makes to the operation of systems that maintain themselves far-from-equilibrium

· Detach function from natural selection.

· View function in terms of contributions to the maintenance of life in a living system within a specific environment.

Autopoiesis and Teleology

Autopoiesis: (from Greek αὐτo- (auto-), meaning "self", and ποίησις (poiesis), meaning "creation, production") refers to a system capable of reproducing and maintaining itself.

Autopoiesis is posited as a fundamental characteristic of living organisms. An autopoietic system is a system that produces and reproduces its own elements as well as its own structures (Luhmann, 2012, p. 32). The concept was introduced by Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela to describe the nature of living systems in general and the organic cell more specifically. In their definition of autopoietic systems, Maturana and Varela stress both the self-production of the system's elements and its boundary in space (Maturana and Varela, 1980, p. 79).

The enzymes of the cell's metabolism produce enzymes as well as the boundary or membrane that safeguards the reproduction of this network of enzymes, thus producing a closed loop of self-production and self-organization. For Maturana and Varela, autopoiesis constitutes the essential characteristic of living beings. In this framework, evolution is reinterpreted in neutralist terms as a natural drift.

The idea of adaptation as optimization of the organism’s traits by natural selection is replaced by one of conservation of adaptation, as the maintenance of a specific form of coupling between the living system and its environment (Maturana and Varela 1984).

Micheal Behe

Behe does agree with common ancestry, but argues that natural selection as the mechanism of evolution is at least inadequate. In Darwin’s Black Box[6] (1996) Behe offers 8 different biological systems that he claims, could not have evolved gradually.

Behe introduces the notion of: Irreducibly Complex Systems

Irreducibly Complex Systems

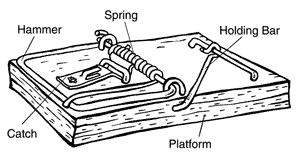

IRC= Several, interacting, well matched parts to perform a specific function, such that the removal of ANY single part would result in the entire system ceasing to function at all. (ex: Mouse Trap- take away any of the five parts and the mouse trap does not work “less well,” but rather it does not function at all.)

His go to example of something exhibiting irreducible complexity is a mousetrap.

He conceives of a mousetrap as having five component parts: platform, hammer, spring, catch and holding bar. The absence of any of these does not mean that mousetrap would function less well; the mousetrap simply wouldn't function at all.

In the relatively new science of biochemistry, Behe points out that we find many examples of irreducibly complex biochemical systems which cannot be explained as having evolved gradually. Until about 50 years ago, biologists thought that cells were very simple systems. Subsequently we have come to learn that cells are in fact, quite complicated little machines (watches?) These biochemical systems present a problem for a gradualist account of evolution because they are an all or nothing deal. Either all the elements need to be present for the system to provide any evolutionary advantage or perform a useful function or it simply doesn't provide any evolutionary advantage whatsoever. Again, the idea is that the system doesn't work less well. It simply doesn't work at all.

· Cellular “machines” cause big problems for Darwinian Gradualism.

· Cillium: Example of a Biological IRC. Cannot be explained by the gradual accumulation of parts.

· Likewise, the blood clotting cascade.

The coagulation cascade is a complex series of steps in response to bleeding caused by tissue injury, where each step activates the next and ultimately produces a blood clot. The term hemostasis is derived from “hem-”, which means “blood”, and “-stasis”, which means “to stop.” Therefore, hemostasis means to stop bleeding. There are two phases of hemostasis. First, primary hemostasis forms an unstable platelet plug at the site of injury. Then, the coagulation cascade is activated to stabilize the plug, stopping blood flow and allowing increased time to make necessary repairs. This process minimizes blood loss after injuries.

But what Behe points out is that if 99.9% of this cascade were in place it would not simply work less well at clotting blood; it would not work at all. This is a classic example of his notion of irreducible complexity. He suggests that Darwinian gradualism cannot explain such systems. He further suggests that deliberate design hypothesis are far more reasonable to account for these instances of irreducible complexity.

His 1996 edition helped bolster a growing “intelligent design” movement which sought to revive William Paley style design arguments, the argument that nature exhibits evidence of design which is beyond the ability of random, mindless mechanistic forces to account for. Himself a biochemist by trade he sparked a national debate not only on evolution, but more broadly the demarcation between science and pseudoscience. From one end of the spectrum to the other, Darwin's Black Box has established itself as the key intelligent design text and an argument that must be addressed in order to determine whether Darwinian evolution is sufficient to explain life as we know it.

In his 2006 second edition, Behe writes an afterword where explains that instances of this irreducible complexity discovered by microbiologists has dramatically increased since the book was first published. That complexity is a continuing challenge to Darwinism, and evolutionists, he maintains, have had no success at explaining it.