Epistemology:

Traditional Account of Knowledge

John Locke and the Causal Theory of Perception

Primary

and Secondary Properties

Locke’s

View in Sum and Implications

Consequences for

Philosophy (et al.)

Opens the door to

Radical Relativism

What do you know?

I

· I know I have a hand.[1]

· I know that Paris is the capital of France.[2]

· I know that gold’s atomic number is 79.[3]

· I know that a rook can move horizontally or vertically on the chess

board. [4]

· I know what a rose smells like.[5]

· I know how to ride a bike.[6]

· I know where is live.[7]

· I know who I am. (most days).[8]

But all these really refer to importantly

different “ways of knowing” or “kinds” of knowledge. In Western philosophy, we have concentrated

mostly of “propositional” knowledge. By

the way, a “propositional belief” is a “that” belief: I believe that… The “proposition” is what comes after the

“that.” (e.g. that the Earth revolves

around the sun, that Tuesday comes after Monday; that square root of four is two).

So much emphasis on propositional knowledge has

lead to the impression that all knowledge is propositional and

that anything worth knowing can be expressed in propositions. (Those “that” phrases I was talking

about.) I think this is problem[9],

and this is one of the things we’ll talking about throughout the semester.

Traditional Account of Knowledge

Plato argues that knowledge is best understood as

“true, justified belief.” That is, to

say that Jose knows that Mary is guilty of cheating on her quiz is to say:

- Jose

believes that Mary is

guilty.

- It

is true that Mary is

guilty.

- Jose

has a good reason

(justification) for his belief that Mary is guilty.

Kn= TJB.

This is referred to that the “Traditional Account

of Knowledge.” As I say, this has been

widely accepted as THE correct understanding of knowledge for the better part of

Western history. More recently it has

been challenged and we will be looking both at the traditional account of

knowledge and its challenges throughout the semester. Today, however, I want to concentrate on how

the traditional understanding of knowledge along with empiricist models of mind

have come to influence contemporary popular conceptions of what can and what

cannot count as knowledge. In the second

half of my lecture today I will be looking at Active Theories of perception and some of its consequences for

knowledge, truth and justification.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave:

Key to understanding Platonic thought is the

distinction between appearance and reality.

Not everything that appears to be true is true, not everything that

appears to be good is good and for Plato, it even followed that not everything

that appears to be beautiful is beautiful.

If this is so, then the role of philosophy is to help us the distinguish

between the truth and mere appearance of truth, goodness and the mere

appearance of goodness, and beauty and the mere appearance of beauty. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy

which addresses the first of these, while Ethics and Aesthetics deal with the

second and third of these.

So how do we acquire knowledge? How do we avoid deception and error? Plato suggested that the senses are

deceptive, and that the most reliable knowledge came from reason and

introspection. He can point to the

reliability of math and geometry to prove his point. Note that mathematical truths can be known

with absolute certainty. We do not need to update calculus textbooks nearly

as often as we need to update physics and biology texts. This confidence in reason and distrust of the

sensory is characteristic of one of the two great traditions in Western

epistemology: Rationalism.

But Plato’s best student and best critic was the

philosopher Aristotle. In contrast to

Plato, Aristotle held that the best way to come to know objective truth, indeed

the ONLY way to come to know objective truth, is via sensory experience. This is the second of the two great

traditions: Empiricism.

These two viewpoints battled against one another

for the next 2000 years. Historically

the was St. Augustine, who was a rationalist, and, in contrast, St. Thomas

Aquinas, an empiricist.

Early Modern Philosophers[10]

|

Continental Rationalists: |

British Empiricists: |

|

•

René Descartes French- 1596-1650 •

Baruch Spinoza Portuguese/Dutch 1632-1677 •

Gottfried Leibniz German- 1646-1716 |

•

John Locke English 1632-1704 •

George Berkeley Irish 1685-1753 •

David Hume Scottish 1711-1776 |

Over time Empiricism came to dominate philosophy

in the United Kingdom, and eventually the United States. It is this tradition, I contend, that has had

the greatest influence on contemporary popular thinking about knowledge, truth

and justification in the United

States. There are several features of

this view that I would like to highlight and ask you to examine. The first of these is the nature of

perception.

John Locke and the Causal Theory of Perception

John Lock (1632 -1704) was one of the three

“British Empiricists” of the Enlightenment period.[11] As am Empiricist, Locke was committed to the

idea that there were no such things as “innate ideas” and that the best, indeed

the only way, to come to know objective truth was via sensory experience.

·

The only way to come to know

the world is through sensory experience.

·

Agrees with St. Thomas

Aquinas- that, “Nothing is in the mind without first having been in the

senses.”[12]

·

Locke claims that we start

life with a blank slate, "tabula

rasa[13]."

Further, Locke rejects the “direct realism” or

“naïve realism” of pre-Modern philosophy. Rather than contend that we directly

grasp reality in perception, Locke, like Descartes, claims we grasp only our

mental representations of reality. We

get the “video feed,” but do not see the world outside directly. The question then becomes” How can we go from

knowledge of our perceptions (the video feed) to knowledge of extra-mental

reality (the world outside)?

·

Points out that there is the

(1)

world and

(2)

there are ideas

about the world.

·

This places critical

importance on determining: What is the connection between reality and

our minds?

The

Problem of Perception and the External World

Whoever wishes to become a philosopher must learn

not to be frightened by absurdities.

------Bertrand

Russell, Problems of Philosophy

These skeptical worries enter Western Philosophy

with a vengeance with Descartes et alia.

·

Are things as they seem?

·

Are there objects

independent of me?

·

Are there other minds?

·

And even if there are…

·

…how could I ever know any

of these things?

Direct

(“Naïve”) Realism: Physical objects are

directly (“immediately”) perceived. We

don’t need to justify an inference from sensory experience to physical reality

because physical objects are the objects of sensory experience.

Representationalism

(indirect realism): The

immediate objects of experience represent the physical objects which cause

them.

Sense

Data Theories: The objects of immediate

experience are sense data—private, non-physical entities, “ideas.”

Phenomenalism:

Physical objects are

reducible to the occurrence of the immediate objects of experience,

Scholasticism embraces a direct realism while

modern philosophy largely rejects it.

But with representational realism immediately comes skepticism about the “External World.”

How then to avoid skepticism: give good reason

for our commonsense belief that there is an “external world? We must then explain the relation between our

experience and “physical objects.”

Phenomenalism for instance, suggests that what we

call “physical objects” are “logical constructions” out of

sense-data—”permanent possibilities of sensation” (Mill). We must also explain the relation between our

sense data and us—and other people’s sense data and them. Neutral Monism suggest that physical objects

and “selves” (minds) are constructed out of the same (“neutral”) items, but in

different ways.

To this end, Locke offers his “Causal Theory of

Perception.”

Causal Theory of Perception ‑ the world interacts with out perceiving

organs and causes our ideas in our minds; Locke’s use of the word “idea” is

very broadly- nearly any mental item can count as an idea, a concept, a memory

or even a simple sensation such as “salty taste.”

So then, the world causes our ideas about

(perceptions of) it.

Note: our ideas about reality are different from

reality itself; ideas are mental but reality is extra mental.

It is therefore crucial to examine the connection

between the two: perceptions and extra-mental reality in detail. What is

the relationship between our ideas and the world? How does the one give us knowledge about the

other? His concerns are not really that

different from those of Rene Descartes

here; however, Locke’s resolution is

radically different. Unlike Descartes,

who sought absolute, indubitable certainty (justification must be apodictic) ,

Locke was after something more modest: probability/ plausibility. Like good scientists today, he was not

looking for beliefs that could be proven true beyond a shadow of a doubt. Rather he is content to call knowledge those

things we can demonstrate true beyond a reasonable doubt.

Our

Mental Ideas and the Extra-mental Reality: Some Important Distinctions

Our “ideas” come in two varieties according to

Locke:

Simple ideas are ideas that cannot be broken down into any component

parts. For example, the idea of “white”

is simple. I cannot explain “white” to

you; I can only show examples of white and hope you get it. Simple ideas arise from simple sensations.

Complex ideas are ideas that can be broken down into component

parts. For example, the idea of

(perception of) a unicorn. I can

explain the idea of an unicorn to you.

To explain a unicorn all one must do is take the ideas of a horse,

white, and a horn and combine them in a certain way. The “idea” of an apple (i.e. one’s perception

or experience of an apple) might include the simple ideas of red, round, sweet,

solid, etc.[14]

Primary and Secondary Properties:

Our experience of objects reveals two kind of

properties: Primary Properties and Secondary Properties.

Primary

Properties

·

Genuine properties of

objective, extra-mental reality.

·

These are the qualities of

the object independent of who or whether anyone is perceiving the object. Thus

these are independent of perception.

These intrinsic features, those it really has,

including the "Bulk, Figure, Texture, and Motion" of its parts.

(Essay II viii 9) Since these features

are inseparable from the thing even when it is divided into parts too small for

us to perceive, the primary qualities are independent of our perception of

them. When we do perceive the primary qualities of larger objects, Locke believed,

our ideas exactly resemble the qualities as they are in things.

Secondary

Properties

·

Properties of our peculiar

experience of reality, that is, of our perception.

·

They are NOT properties of

the object at all.

·

These properties only occur

in the mind of the perceiver and only at the moment of the perception. They endure only as long as the perception

endures. Thus these are perception

dependent.

These are qualities not in the thing itself, but

rather the powers it has to produce in us the ideas of

"Colors, Sounds, Smells, Tastes, etc." (Essay II viii 10) In these cases, our ideas do not

resemble their causes. Indeed,

the actual causes are in nothing other than the primary qualities of the

insensible parts of things.

Two

ways to tell the Difference Between Primary and Secondary Properties:

1. To change a primary quality of the object you

have actually have to change the object itself, but to change a secondary

property one need only change the conditions of perception.

2. Primary properties can be experienced by more

than on sense, but secondary properties can be experienced by one sense alone.

Consider the idea (perception) of an apple:

It is a complex idea composed of, among other

simple ideas, the ideas red, round, sweet, and solid.

According to the criteria

Locke provides, which of the apple’s perceived properties are primary (really

“in” the apple, and which are secondary (perception dependent, having no

reality apart from perception)?

·

Red is secondary- (I would

no longer see red if I were to change the lighting or I stared at a bright

green poster board. Also I have access

to the color of things through only one sense: vision.)

·

Round is primary- (I would

have to cut or smash the apple to change its shape. Also, I have both visual and tactile access

to the shape according to Locke.)

·

Sweet- secondary.

·

Solid- primary.

Locke’s View in Sum and Implications:

Thus, for Locke, we gain knowledge of the

objective world via the simple and complex ideas caused in us by the objects

and they inform us of the primary

properties of the object as well as provide us with the secondary

properties given to us in experience.

But this means that we must be careful about distinguishing primary and

secondary when making claims about reality.

There is no point is arguing about whether an object has a secondary

property or not, or to what degree.

Notice there is no point to us arguing about whether the soup is “too

salty” or not since the very same soup may cause in me a “too salty” secondary

property, but in you cause a “not salty enough” secondary property. Salty taste is a perception dependent,

secondary property. Further, it might

not even cause that sensation in me the next time I taste it if, for instance,

I drink something even saltier than the soup in the meantime. [15] As such is it not the proper subject for

serous or scientific discussions. [16]

Since secondary properties are not actually

properties of objects, but rather merely properties of the perception of

objects, they are not fixed nor stable.

If we had evolved differently, say as sentient vegetation, “salty taste”

would not happen at all. Had we all

evolved like snakes, “sound” wouldn’t happen at all. Though sound

waves would continue to be just as they are. Therefore, serious inquiry (science)

should confine itself to primary properties.[17]

Note: This view

of knowledge suggests that what can be known of objective facts and perhaps

math. But if you are not talking about

these matters, you are not in the business of saying anything true or

false. Everything else is relegated to

“matters of opinion.” More on this

later.

What are the primary properties properties of?

Locke realized that there must be some “ground”

for these properties. That is, the

primary properties must be property of something. Properties cannot exist on their own. (i.e. What is solif and round?”) So his

answer is that primary properties (these extra-mental, non-perception-dependent

properties), were properties of “Physical Substance.”

Physical Substance: (Stuff) – but we can know very little about

physical substance as such since we never directly perceive it. We only perceive our perceptions and they are

merely properties of substance, not the substance itself.

Locke uses and old metaphysical notion of substance:

that of which one predicates.

Nevertheless, since we do not directly perceive physical substance,

there really isn’t much more that we can know about it. Locke says of physical substance that it is

“something that I know not what.”

Therefore: Our ideas are caused by the physical substance; all ideas are mediated

by your senses; what causes the ideas is the physical substance that never

directly have contact with. While our

mental experience is rich with both primary and secondary qualities, the objective

world can only be said to possess the primary properties. Secondary properties would name subjective

experiences only, not the stuff of serious scientific inquiry or discourse

pertaining to objective truth.

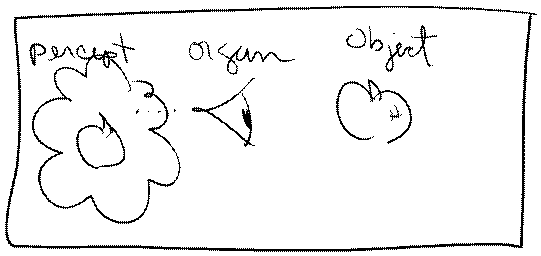

Locke’s Causal Theory of Perception

You have an object (say an

apple) and it interacts with our perceiving organs (say our eye) and causes

in us the perception of an apple.

While the

perception has the secondary properties of red and sweet as well as the primary

properties of round and solid, the actual apple has only the primary properties

of round and solid.

Note then that we see with Locke the beginning of a delineation of the

domain of meaningful, legitimate inquiry and dispute. We see that knowledge is best regarded as propositional

disputes regarding the primary qualities of physical substance. All else is dubious and probably not

something about which we can meaningfully dispute or argue. Shortly after Locke we see Hume explicitly stating

as much:

"When we run over libraries, persuaded of these

principles, what havoc must we make? If we take in our hand any volume; of

divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain

any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain

any experimental reasoning concerning matter of act and existence? No.

Commit it then to the flames: For it can contain nothing but sophistry and

illusion." [18]

Logical Positivism

Logical Positivism followed the linguistic turn[19] in

philosophy. Once it was realized that

truth is a relation which holds between sentences and the world, many

traditional questions of philosophy were recast into questions about the

relations between our language and our experience of reality. Logical Positivism marks a development in

this historical moment of Philosophy.

See: (http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/6q.htm)

Linguistic

Tasks:

There are many uses of language, that is, we

achieve all sort of ends with language:.

(e.g. Assertions, Commands, Questions, Interjections, Poetry

Recitations, etc.) If we accept the

"Traditional Account of Knowledge" which claims that “knowledge”

equals “true, justified propositional belief,” the only sort of sentences that

express knowledge claims must be assertions.

Traditional Account of Knowledge: "knowledge” equals “true, justified

propositional belief (Kn=TJB)

Assertions: The sort of sentence that has a truth value. Only this sort of sentence is meaningful

according to positivism because only this sort of sentence actually informs us

(conveys information).

These are to be distinguished from

Pseudo-assertions.

Pseudo-assertions: The sort of sentence that may appear meaningful at first but in fact is

not. It does not have a truth value and

does not provide us with information.

Keep in mind that when we speak of a sentence

having a “truth-value” we do not mean that the sentence IS true, but only that it

is either true or false- has one of the two possible truth values.[20] What the Logical Positivists point out is

that, before wasting a lot of time arguing about whether a given sentence is

true or false, we should first make sure that it is an assertions; that is, we

should first make sure that it is even the kind of sentence than could be

true or false.

Assertions usually take the form of declarative

sentences (i.e. sentences having a certain grammatical structure –subject-

verb- predicate), but not all declarative

sentences are assertions.

Consider for example:

“In

the swirling vortex of love, a candle burns.”

This IS a

declarative sentence.

____Candle

│burns ________

\

a \in

Vortex_____

\the \of \swirling

love

This is NOT an assertion. (To check, ask yourself, “Is it true? Does there indeed burn a candle in the

swirling vortex of love?- Or is it

false? Has the candle in the swirling vortex of love gone out? Is there a light bulb there now? A neon sign instead perhaps? Perhaps a more environmentally friendly LED?)

I doubt anyone would be willing to say that this

sentence is true or false. Rather, they

would say that it is neither true nor false. Thus it is NOT an assertion. It neither informs nor misinforms. It lacks either “true value,” instead having

none.

But note: the sentence

“In the room next-door a candle burns.”

This IS an assertion.

What’s the difference? Not the grammar. The grammar is identical to the first

sentence. Both are declarative sentences

with a subject and predicate.

____Candle

│burns ________

\ a \in

room_____

\the \next-door

Further, consider these:

Kwai

gives you all the goodness of garlic.

This

product was scientifically formulated to help you manage your hair-loss

situation.

History

is the unfolding of consciousness to itself and for itself where the Absolute

presents itself as an object and returns to itself as thought.

We

did a nationwide taste test and you know what?

Papa John’s won big time!

It

is our destiny to rule the world.

With

our Lightspeed Reading Program, you will virtually read 2, 3, 4, even up to 10

times faster.

With

Elastizine you’ll see an average of 28% increase in younger looking skin.

Love. It’s

what makes a Subaru a Subaru.

How many declarative sentences are contained in

the following? How many assertions?

Hey Ladies! How

would you like to have drop-dead gorgeous skin without surgery? How would you like being stopped by customs

agents because you look younger than you Passport date? Well that’s what happens to users of Amino

Genesis. While other manufactures

recycle the same old stuff and call it new, Amino Genesis has cracked Nature’s

code.

Have trouble

getting to sleep but can’t take a sleep aid?

Millions do. That’s why the

hottest new sleeping pill is not really a sleeping pill at all. Relicore PM.

Take Relicore PM and get a restful sleep you need. Relicore PM, in the diet and sleep aid

aisles.

Have you tried everything to lose weight? Sweaty exercise is boring and takes too much

time. Crazy diets don’t work and always

leave you feeling hungry and deprived.

Wish there were another way? Well

now there’s Tone and Trim. Based on years of research, this

revolutionary new break-through technology was scientifically formulated by a

leading medical doctor to help you lose those unwanted inches without diet or

exercise. Just take two small capsules a

day, one before breakfast and one before bed, and voilá! You’re on your way to s slimmer sexier

you! Tone and Trim is all natural; there’s no stimulants and no danger

of harmful side effects. Tone and Trim works with you body’s own

calorie burning mechanisms like a super turbo boost, leaving you leaner and

more vitalized. Can’t believe any

weight-loss program could be so simple and easy? Believe it!

Don’t waist your time on crazy fad diets or strenuous exercise that

doesn’t work! Lose that ugly fat and

have the body you’ve always dreamed of with Tone and Trim. What are your

waiting for? Pick up the phone and call

today. Don’t let another day go by

without your Tone and Trim body!

The one 20th century philosopher A. J.

Ayer actually mentions in his Language, Truth

and Logic is:

“The Absolute enters into but is itself incapable

or progress or change.”

This was a sentence taken from the philosophical

writings of F. H. Bradley. In Ayer’s

view, it is a perfect example of nonsense.

More problematic, it is nonsense masquerading as “philosophy.” The

unwitting take it seriously and even dispute whether it is true or not. What a waste of time!

But how do you tell a genuine assertion when you

see one? Not the grammar. So then what?

The criterion, used by Logical Positivists to

determine if a sentence is a meaningful assertion is called the "Criterion

of Verification."

Criterion

of Verification: "If a sentence is unverifiable, even in

principle, then it is meaningless; it is not an assertion; it is neither true

or false."

Oxford philosopher A.J. Ayer (1910-1989), is the person probably most

responsible for helping to make this movement so widely know. In Ayer’s Language,

Truth and Logic he claims that a genuine

assertion can be true or false in only

one of two ways. Statements or

propositions (assertions) may be true or false by definition (analytic or what

18th Century philosopher David Hume[21]

would have called “relations of ideas,”)

or they may be true or false as a statement of observable fact (empirical or

what Hume would have called “matters of

fact and existence”).

For example, the claim “All bachelors are unmarried.” is true by

definition. And the claim “Some

bachelors are married.” is false by definition.

This is because the predicate “unmarried” only restates part of what is

meant by the subject term. Since

“bachelor means “unmarried male,” to say that a bachelor is married

would be logically inconsistent and therefore false.

Notice the truth or falsity of such claims can be known a priori (independent of

experience).

A priori: Known or justified independent

of experience.

If you came to my office and told me that your friend is in the

hallway and that he was a married bachelor, I would not even have to get up

from my desk to KNOW that there was no married bachelor friend of yours in the

hall. I can know this independent of any

particular experience (a priori).

Now suppose you claimed that “All bachelors are unmarried.” and I

expressed a doubt about this. I tell you

I want you to prove it to me. I

suppose you could go door to door and

do a survey: Knock, Knock, Knock. Excuse

me sir are you a bachelor? You are? I

see, but let me ask you now then, are you also

an unmarried male?”

But this would be a colossal waste of your time.

For claims like “All bachelors are unmarried.” we need take no poll to verify nor do any

sort of experiments, etc.. We need only

to know the meaning of the terms involved in order to know whether they state a

truth or a falsity. This is why they can

be known a priori. This is why Hume

called them "Relations of Ideas."

Relation of Ideas: Definitional-a priori, Analytic, A=A, trivial (usually),

non-augmentative (usually). Ex: “All

vixen are foxes.” But (perhaps) also

math and geometry.

Now if you came to my office and told me you brought your pet unicorn

to campus and asked me to come out into the hallway to see you pet unicorn, I

would be VERY skeptical and maybe think you’re a little crazy. However, I could not know a

priori that there was no unicorn in the hallway. That’s because there is nothing about a

unicorn that is a logical contradiction.

The reason I think that there are no unicorns is based on experiences

(We’ve looked and never found one.) so it is always possible that some future

experience would undermine this belief.

If I really wanted to make sure there was no unicorn out in the hallway

I would

have to get up from my desk and

poke my heard out into the hall. I don’t

expect to see anything, but there is the possibility that when I did I’d say, “Damn, would you look at that.”

The claim “All bachelors are unhappy.” on the other hand is not true

“by definition.” “Bachelor” does not

contain the concept of “Unhappy.” If

this sentence is true at all it is true as a matter of fact about the world

(and if it is false, it is false as a matter of fact about the world). To discover the actual truth-value (T or F) of the claim we would have to conduct

an empirical study. Since the claim “All

bachelors are unhappy” and the claim “It is not the case that all bachelors are

unhappy.” are both logically consistent, we cannot know which of them is true

(accurately states a fact about the world) a priori.

Since the predicate is NOT merely a restatement of the subject

concept, but rather a different concept entirely, the sentence is said to be “synthetic.” It weds two distinct ideas. Take for example “All Swans are white.” Swan does not MEAN white bird. We easily imagine a swan with of a different

color. So the only way to see whether

this synthesis in fact holds is to go and to look. Incidentally, it was widely believed that all

swans were white. Then it was discovered

empirically that there was a species of black swans. Notice that experience of the world is what

grounded the synthetic claim in the first place and it was experience of the

world which overturned and disconfirmed that same claim.

Matters of Fact: Empirical, Synthetic, A=B, interesting (usually), augmentative

(usually). Ex: “All Swans are white.”

Loosely speaking these are scientific claims.

If however, the truth of a sentence can be determined neither from the

meaning of the words (a priori) nor by employing the scientific method

(empirically) then the sentence fails the criterion of verification. The sentence is devoid of cognitive content

and is literally nonsense according

to the Positivists. This would be true

for such pseudo-assertions as “Kwai gives you all the goodness of garlic.” but

also of such claims as “An immaterial soul exists.” or ethical sentences

containing such terms as “ought,” “should,” “good,” or “bad.” They are non-sensical and therefore not

sentences which impart knowledge.

Consequences for Philosophy (et al.):

Many (all?) the traditional philosophical answers to traditional philosophical

questions seem to fail the criterion.

For example:

Natural Theology

e.g. “There is a God.”- Not a relation of ideas nor a matter of fact

Turns out to be meaningless on these grounds.

Note: “There is no God.” is equally meaningless on Positivist grounds.

Metaphysics

e.g. “Immaterial objects exist.

Aesthetics

e.g. The Miami City Ballet is a better ballet company than the San

Francisco Ballet.

Ethics

e.g. Abortions is wrong. (Or, Abortion is not wrong.)

Specifically, Metaphysical Theories, Theological Theories,

Epistemological Theories, Ethical Theories, Aesthetic Theories, seem to consist

of sentences that are neither relations of ideas nor matters of fact. Consequently, according to the criterion of

verification they are neither true nor false.

They are meaningless. It is not

clear what, if anything, could count a “Ethical Knowledge” for instance or an

“Ethical Truth” on their view. These

pseudo-assertions convey no knowledge, but rather at best are a kind of poetic

or emotive use of language. The realm of meaningful discourse is very narrowly

circumscribed.

Some Positivists claim that the reason for the seeming irresolvable

“disagreements” on ethical matters is simply that ethical judgments have no objective validity. Ironically, the Positivist accounts for these

‘disagreements” by, in an importance sense,

denying that there really every has been any. Note that a curious consequence of this view

is that there are no, nor have there ever been nor can there ever be any real ethical disputes. The Anti-abortion activist who says,

“Abortion is wrong!” and the Pro-reproductive rights activist who says,

“Abortion is NOT wrong!” don’t really disagree about anything (any

fact).

I think this a very narrow view of what constitutes meaningful

discourse. This think this is a totally

inadequate account of what’s going on in Ethics in particular and Philosophy in

general. However, I think a little

Positivism is a good thing. I think it a

very useful exercise to ask oneself, “What, if anything, could possibly prove

that claim true or false?” And if it

turns out that the answer is, “Nothing.”

then one has good reason to be deeply suspicious of the “claim.”

But my objection to Positivism is not merely the fact that, if

correct, it would largely put me out of work.

The criterion of verification is self-referentially incoherent. That is, the criterion fails itself. Take the sentence:

“If a sentence is unverifiable, even in principle, then it is

meaningless.”

This sentence above is neither a relation of

ideas (that is, a true-by-definition-tautology) nor is it a matter of fact

(that is, something that can be proven by employing the scientific

method). Thus either the criterion is

meaningless or false. There is no way

that it could be true.

Some positivists suggested that it be read as a

recommendation (a mild imperative).

“Regard as meaningless any sentence which is

unverifiable.”

But if it is only recommendation, we are free to

either accept it of reject it. Given the

excessively confining and impractical restrictions the criterion imposes on

“meaningful discourse” and inquiry, many (me) have chosen to reject it.

All experience is mediated by active mind. This was not appreciated until relatively

recently. (The myth of the “given” and

the “innocent eye” still persist today.)

Immanuel Kant and Active Mind

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) marks an important

development in Philosophy and conceptions of “Mind.” At this point in the history of Western

philosophy, two great opposing traditions had come to an impasse of sorts: Rationalism

and Empiricism had both seemed inadequate to account for human

knowledge. Rationalism seemed unable to

account for knowledge of our world of experience. Conversely, Empiricism seemed unable to

account for the necessary truths of math and geometry or even the universality

of the laws of nature. Taken to their

logical extremes, both seemed to end in skepticism (either Descartes’s or

Hume’s). Kant’s solution to the impasse

was to revision the very nature of knowledge and experience. The mind does not merely receive information in

the act of perception; the mind shapes that information and constructs

experience out of the raw sense data that the world provides. This is sometimes referred to as Kant’s

“Copernican Revolution” in Epistemology.

Rather than asking “Is knowledge/ understanding possible?” Kant asks “How is

knowledge/ understanding possible?”

Rather than asking “How does knowledge impress itself onto mind?” (passive

metaphor) Kant asks “How does mind construct knowledge?”

To accurately account for what is going on in

perception it is necessary to see human experiences as having different

content, but a consistent “form.” If we

were to abstract all content from human experience we would arrive at the pure

form of experience. Think of it a blank

template into which mind pours all sensory information and thus arrives at a

coherent experience. Alternatively think

of my (very old, MS DOS based) Maillist program that can organize records

according to one and only one pattern.

No matter what data it receives, it will always organize them in the

same fashion. In this case it was: First

Name, Last Name, Telephone Number, Street Address. Whether the data are for my mom, my sister,

the guy I knew from high school, the form of the record would always be: First

Name, Last Name, Telephone Number, Street Address. Even if the cat walked

across the keyboard it would be: First Name, Last Name, Telephone Number,

Street Address.

Thus I have knowledge of how my 100th record will

look (in broad outline) in advance of actually reviewing the 100th

record. That is, I have a

priori knowledge of the 100th record. My knowledge is not grounded in the

particular experience of my 100th record, though it is grounded in

experience in general. Though I don’t

know what the CONTENT of the record is, I know the form because when I am

referring to this program’s records, I am referring to products of its

organizing function which does not/ cannot change.

Another illustration of what Kant has in mind

here can be seen in those “Magic Eye” posters.[22] At one moment they look like flat two

dimensional images. The next they look

like a three dimensional image. What is

different from one moment to the next?

Is the poster giving you something different when it looks two

dimensional from what it is giving you when it look 3 dimensional? No.

What is different is what YOU are doing with the input from the poster,

the activity of you mind in perception.

But this is just a more noticeable example of what the mind does

constantly. The reason you see reality

as three-dimensional is NOT because “that’s how the world really is,” but

rather because that’s how your mind (and every other normal, healthy human

mind) is shaping the sense data.

Theoretical physicists might talk of reality in multiple dimensions, but

even they don’t perceive it that way.

They come to that understanding purely theoretically. Perhaps aliens from outer space perceive

reality in more dimensions. Perhaps’ s

God perceives it that way. But not

humans. Not now, not ever, says

Kant. We will always only “image” the

world as three dimensional. (And the

same thing goes for unidirectional time.)

Kant is very specific about what these forms and

categories of experience are, but I’ll only refer to a few for illustration

purposes.

Space and Time are the two pure forms of experience according to Kant.

All human experience will/ must conform to 3

dimensional Euclidian Space.

All human experience will/ must conform to

unidirectional time. (Past to present to

future).

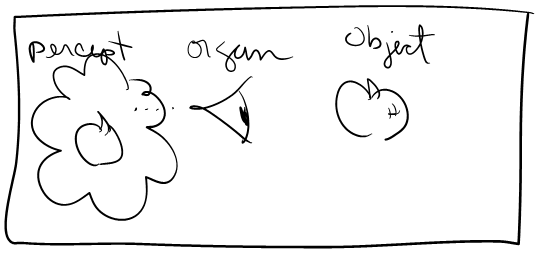

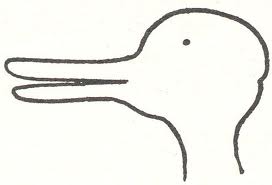

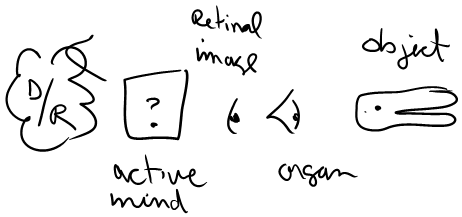

For another example, think of visually ambiguous

images, specifically the “Duck/Rabbit.”

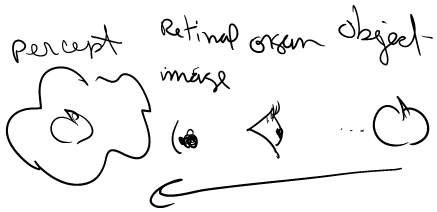

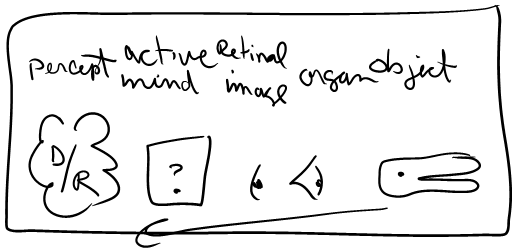

This phenomena shows why the old model of passive

perception is inadequate for understanding how perception works. For Locke, he thought it was enough to talk

about the object, the perceiving organ and the perception. On this view the object “impresses” itself on

the mind and the mind is simply the

inert passive recipient of the information.

We can

complicate this simple model a bit by talking about the object, the organ, the

retinal image, and the perception. But

again, on this model, the perception is understood as the inevitable product of

the retinal image. Mind plays no active

role.

We can

complicate this simple model a bit by talking about the object, the organ, the

retinal image, and the perception. But

again, on this model, the perception is understood as the inevitable product of

the retinal image. Mind plays no active

role.

![]()

But in the case of ambiguous images, the poverty

of this view is revealed. In the case of

the “Duck/Rabbit” image, I can see a duck or I can see a rabbit, that is I can

have the duck-perception or the rabbit-perception and which perception I have

cannot be explained in terms of the object, the organ or the retinal

image. When I have the duck-perception,

the object, the perceiving organ and the retinal image are the same as when I have the rabbit-perception. There must be some other factor that

explains the difference in perception, and that factor is the activity

of mind. The old Lockeian model

of mind simply cannot account for the phenomena.

Opens the door to Radical Relativism:

Kant believed that our (human) empirical

knowledge was universal (NOT RELATIVE) because the pure forms of experience and

the categories of thought were universal for all humans. Therefore, he was

certain that what is true for one human is true for all humans.[23]

BUT....one might object to Kant’s view.

For instance, what if we do NOT all put the world

together in basically the same way (e.g. woman according to a female template,

men according to a male template)? If

“Men are from mars and women are from Venus” then we are not experiencing the

same worlds because we are building our worlds, shaping our experience, with

the same input, but according to different templates. We are, in a very real sense, living in

different worlds, and truth must be relativized to groups of cognizers who

possess the same template. Rather than

univalent, truth becomes bivalent or, perhaps, multivalent. Truth is potentially as multifaceted as there

are minds, and no basis would exist for claiming that any particular worldview

was privileged among the plurality.[24]

This realization gave rise to the

Post-modernists’ notion that there is no one point of view from which Truth can

be determined. Imagine two groups of people, one who could only see the duck

and one that could only see the rabbit.

Which group is seeing what is “really there” and which group is wrong? Well of course we see in this example that

there is no reason to think that either group is privileged here. Further, the only reason we could have to say

that one of them has truth and the other has falsehood and is not seeing the

world “correctly” would be to advance a political, economic or social agenda.

We see with Empiricism in general and Locke in particular a focus on

propositional knowledge. The substance

of this knowledge is confined to empirical claims and logical tautologies. Claims not falling within the categories fall

outside the domain of knowledge and, consequently, serious inquiry. However A .J. Ayer’s and the Positivist’s

account of knowledge seems too narrowly circumscribed. They, in essence, created a club so exclusive

that it wouldn’t let them in.

We also noted that the passive model of perception coming to us from

Empiricism is flawed and inadequate to account for human experience and knowledge. The mind is active in perception and our

experience of the world is a result of that the world is giving us and what our

minds do with this input. The act of

perceiving the world is inseparable from the act of interpreting the

world. Kant offers this account, in

part, to answer the skeptical worries of both Rationalism and Empiricism. But we notes that he inadvertently opens the

door to entirely new challenge to those seeking absolute truth and universal

knowledge.

Despite the shortcomings of both Positivism and passive models of

mind, both remain extremely influential on contemporary popular understanding

about the nature and substance of knowledge and truth.