Why Self-Driving Cars Must NOT Be Programmed to Kill

Self-driving

cars are already cruising the streets. But before they can become widespread,

carmakers must solve an impossible ethical dilemma of algorithmic morality.

When it

comes to automotive technology, self-driving cars are all the rage. Standard

features on many ordinary cars include intelligent cruise control, parallel

parking programs, and even automatic overtaking—features that allow you to sit

back, albeit a little uneasily, and let a computer do the driving.

So it’ll

come as no surprise that many car manufacturers are beginning to think about

cars that take the driving out of your hands altogether (see “Drivers Push Tesla’s

Autopilot Beyond Its Abilities”). These cars will be safer, cleaner, and more fuel-efficient

than their manual counterparts. And yet they can never be perfectly safe.

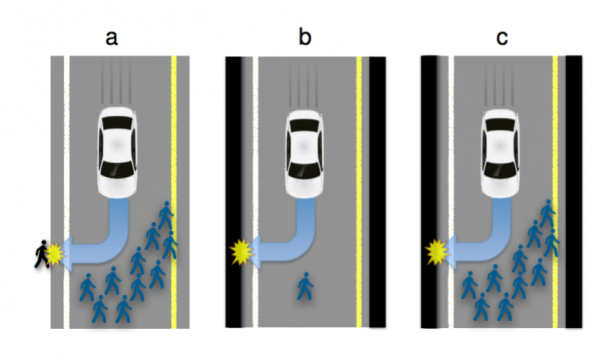

And that

raises some difficult issues. How should the car be programmed to act in the

event of an unavoidable accident? Should it minimize the loss of life, even if

it means sacrificing the lives of its occupants, or should it protect the

occupants at all costs? Should it choose between these extremes at random?

Here is the

nature of the dilemma. Imagine that in the not-too-distant future, you own a

self-driving car. One day, while you are driving along, an unfortunate set of

events causes the car to head toward a crowd of 10 people crossing the road. It

cannot stop in time to simply avoid an accident, but it can avoid killing the

10 people by steering into a wall. Doing so, however, would kill you, the owner

and occupant. What should it do?

One way to

approach this kind of problem is to act in a way that minimizes the loss of

life. By this way of thinking, killing one person is better than killing

10. Some have argued that, were

self-driving cars programmed to make that calculation, and if people knew that

they were so programmed, fewer people (anyone?) would buy self-driving. These cars are programmed to sacrifice their

owners. Paradoxically, then more people are likely to die because

ordinary (non-self-driving) cars are involved in so many more accidents than

would be the case were they all or mostly replaced with the safer self-driving

ones. The result is a Catch-22

situation.

Of course,

we could try to convince people to be more altruistic and purchase the cars

anyway. Alternatively, government could

mandate self-driving cars, perhaps outlawing manual cars or taxing them very

heavily. Or we could simply lie to the

consumer and tell people that the cars that they were buying would not

sacrifice their lives in such cases (even though they would). But all of these

solutions are fraught with problems both ethical and practical.

I propose

another solution: we simply do not program self-driving cars to always

sacrifice the occupants in such cases.

Rather we leave the decision of how the program the cars up to the

consumer/occupant. I think this decision

can be defended on three grounds.

If we treat

the cars as a sort of “agent for the owner” then it should be an extension of

the owners will. When a client hires an

attorney, the attorney is an agent of the client and is required to follow the

direction of the client, regardless of utilitarian considerations of benefit to

others. On a similar view here, it is in

the interest of protecting the rights and autonomy of the agent that we leave

the decision as to how to program the car to her.

Further, once

the public is assured that their cars will not kill them, deliberately, they

will be more comfortable utilizing self-driving cars. Their use will increase and we will see the

benefits of reduced death and injury which result from an increase in

self-driving vehicles. Thus the result

of this policy are preferable to the results of mandating the

occupant-sacrificing programming.

Thirdly, over

time, particularly if the public sees that such situations (the good of the

many vs. good of the occupant) are in fact very rare, they might very well grow

more comfortable making the decision to allow to car to sacrifice their lives

if it is the only way to minimize death and/or injury. Indeed some, (one might suppose Peter Singer

among them) would already make that decision.

I think this number would likely grow over time, particularly if there

were legal ramifications (civil law suits, liability issues, insurance rates

rising) for not making that decisions.

The public, I believe, for moral, practical and convenience reasons

would eventually be nudged into making the more “altruistic decision.” If that is so, we can have our cake and eat

it too. The public would use

self-driving cars and (many/ most) times where the car must decide between the

life of the occupant and the life of others it will, following the will of the

occupant, make the injury/death minimizing decision.

For these

reasons I argue that self-driving cars ought NOT be programs to kill, at least

not by default, but rather that that decision be left to the owner/occupant

herself.