AML4213:

Early American Literature—Journeys to America

Spring 2012

Dr. Bruce Harvey

Slide Show #1:

Domestication of Wild Indianness

This depiction

of The Death of Jane McCrea was painted in 1804 by John Vanderlyn

(detail):

The

Rescue is a

large marble sculpture group assembled in front of the east façade of the United States Capitol building and exhibited there from

1853 until 1958 when it was removed and never restored. The sculptural ensemble

was created by sculptor Horatio Greenough (1805–52).

Prof. Harvey notes: little Indian = no threat, easily subdued by robed

colonial-Euro person; Indian looks up like baby, as if seeking tutoring (vague

Christ & Madonna, also); Indian physicality absorbed into colonial-Euro

intellection (figures are fused).

Slide Show #2: The American Sublime in Art

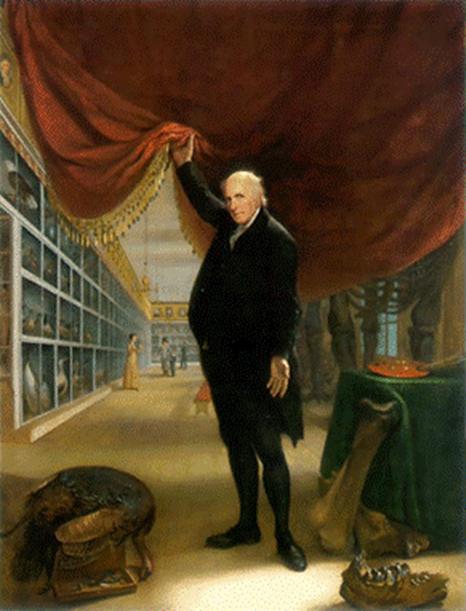

Charles W. Peale (1741-1827), The Artist in his Museum—1822.

Prof. Harvey notes: Peale applied Enlightenment principles to nature by

creating the first rationally-classified American natural history museum.

Peale was a painter, naturalist, and all-round scientist. He was a friend

of President Jefferson, and saw his naturalist museum as bringing "rational

amusement" (a line in the tickets for the museum) to the American

citizenry. Here, Peale depicts himself inviting the viewer-spectator to

enter into the edifying museum. The bones beneath the curtain to the right are

mastodon bones. Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark on their famous

expedition, in part, in the hopes of finding living wooly mammoths... which he

believed might be still existing somewhere in "Indian" territory

across the Rocky Mountains. The birds, etc., in the grid-like boxes are

taxidermist specimens. Note Peale's somber expression; we're not supposed to

gape at nature with mindless enthusiasm, or bond with it!

Frederic

Edwin Church (1826 –1900), Cotopaxi (1862).

Prof. Harvey notes: no human “subject” position; instead we are drawn into vast

sublime scene which is everywhere/all-subsuming.

Slide Show #3: American Romantics Imagine Nature

Henry David Thoreau,

from Walden (1850):

Flint's Pond! Such is

the poverty of our nomenclature. What right had the unclean and stupid farmer,

whose farm abutted on this sky water, whose shores he has ruthlessly laid bare,

to give his name to it? Some skin-flint, who loved better the reflecting

surface of a dollar, or a bright cent, in which he could see his own brazen

face; who regarded even the wild ducks which settled in it as trespassers; his

fingers grown into crooked and bony talons from the lodge habit of grasping

harpy-like;- so it is not named for me. I go not there to see him nor to hear

of him; who never saw it, who never bathed in it, who never loved it, who never

protected it, who never spoke a good word for it, nor thanked God that He had

made it. Rather let it be named from the fishes that swim in it, the wild fowl

or quadrupeds which frequent it, the wild flowers which grow by its shores, or

some wild man or child the thread of whose history is interwoven with its own;

not from him who could show no title to it but the deed which a like-minded

neighbor or legislature gave him- him who thought only of its money value;

whose presence perchance cursed all the shores; who exhausted the land around

it, and would fain have exhausted the waters within it; who regretted only that

it was not English hay or cranberry meadow- there was nothing to redeem it,

forsooth, in his eyes- and would have drained and sold it for the mud at its bottom.

It did not turn his mill, and it was no privilege to him to behold it. I

respect not his labors, his farm where everything has its price, who would

carry the landscape, who would carry his God, to market, if he could get

anything for him; who goes to market for his god as it is; on whose farm

nothing grows free, whose fields bear no crops, whose meadows no flowers, whose

trees no fruits, but dollars; who loves not the beauty of his fruits, whose

fruits are not ripe for him till they are turned to dollars. Give me the

poverty that enjoys true wealth. Farmers are respectable and interesting to me

in proportion as they are poor- poor farmers. A model farm! where the house

stands like a fungus in a muckheap, chambers for men horses, oxen, and swine,

cleansed and uncleansed, all contiguous to one another! Stocked with men! A

great grease- spot, redolent of manures and buttermilk! …. White Pond and

Walden are great crystals on the surface of the earth, Lakes of Light. If they

were permanently congealed, and small enough to be clutched, they would,

perchance, be carried off by slaves, like precious stones, to adorn the heads

of emperors; but being liquid, and ample, and secured to us and our successors

forever, we disregard them, and run after the diamond of Kohinoor. They are too

pure to have a market value; they contain no muck. How much more beautiful than

our lives, how much more transparent than our characters, are they! We never

learned meanness of them. How much fairer than the pool before the farmers door,

in which his ducks swim! Hither the clean wild ducks come. Nature has no human

inhabitant who appreciates her.