Hawaii’s Statehood

Alexandria Martin

Hawaii and Nineteenth-Century Commerce

The exact date is unknown and probably will remain so forever.

But sometime after the beginning of the Christian era, Polynesians first

set foot on these islands. Linguistic and cultural evidence suggests that the

first inhabitants came from the Marquesas group, to the north of Tahiti. During

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, waves of immigrants from Tahiti

overwhelmed and absorbed the original people. Since the earliest Hawaiians were

likely somewhat smaller than later immigrants, they may form the basis for the

legends of the menehunes, who were pictured by the later Hawaiians as

hardworking elves.

Hawaii assumed importance in the east-west fur trade and later as the

center for the Pacific whaling industry. Captain James Cook, the great Pacific

explorer, happened upon the islands during his third voyage in 1778.

Hawaii's long isolation ended at that moment.

Soon, King Kamehameha the Great embarked on his successful campaign to

unite the islands into one kingdom. At

about the same time of the decline of the Asian fur trade Hawaii extensive

sandalwood resources began to deplete in the 1830’s.

Despite the circumstances, Hawaii assumed importance in the east-west fur

trade and later as the center for the Pacific whaling industry.

Change came at a rapid pace, as both education and commerce assumed

growing importance. The old

Hawaiian culture disappeared rapidly under the onslaught of new ways, new

peoples, and new diseases, to which the previously isolated Hawaiians were all

too susceptible. Whaling and the

provisioning of the whaling fleet brought new money to the island economy.

At times, as many as 500 whaling ships wintered in Hawaiian ports,

principally Lahaina and Honolulu to pick up the valuable goods that Hawaii

possessed.

In 1835, the first commercial production of sugar cane began, and this crop took on ever increasing economic importance, especially after the decline of the great whaling fleets. Native Hawaiians did not take kindly to the tedious labor of a plantation worker and, in any case, the native population had been seriously depleted by disease. Thus, there began the importation of labor from Asia and the Philippines and other areas of the world. It is this varied population that gave rise to the immense variety of Hawaii's present inhabitants. Threatened constantly by European nations eager to add Hawaii to their empires, sugar planters and Americans businessmen began to seek annexation by the United States. This, too, would give them the advantages of a sugar market free of tariff duties.

Sugar was by

far the principal support of the islands; and profits and prosperity hinged on

favorable treaties with the United States, Hawaiian sugar's chief market,

creating powerful economic ties. The plantation owners were, for the most part,

the descendants of the original missionary families who had brought religion to

the islands in the wake of the whaling ships. As ownership of private property

came to the islands, the missionary families wound up owning a great deal of it.

Hawaii has little in the way of mineral wealth, so the land was useful only for

agriculture. In a day when unrefrigerated sailing ships such as Captain Matson's

"Falls Of Clyde" were the only means to ship produce to the U.S.

Mainland, sugar, and to a lesser extent coconuts, were the only produce that

could survive the sea voyage.

Imperialistic

Tactics

The American citizens themselves, the plantation owners, were rankled by

the fact that the US government actually made more profits from their sugar then

the plantation owners themselves did. To evade the tariff, it became necessary

to the plantation owners that Hawaii cease being a separate and sovereign

nation. Finally, a treaty of

reciprocity was negotiated in 1875 and this brought new prosperity to Hawaii.

American wealth poured into the islands seeking investment.

Political control by Hawaiian royalty and the growing influence of

Americans began to cause conflict. In

1887, during the reign of Lili`uokalani' s brother, King Kalakaua, a group of

planters and businessmen, seeking to control the kingdom politically as well as

economically, formed a secret organization, the Hawaiian League. Membership

(probably never over 400, compared to the 40,000 Native Hawaiians in the

kingdom) was predominantly American, led by Lorrin A. Thurston, a lawyer and

missionary grandson. Their goal, for now, was to "reform" the

monarchy. But what was "reform" to the Americans was treason to the

people of Hawaii, who loved and respected their monarchs.

It is important to recall that, unlike the hereditary rulers of Europe,

Hawaii’s last two kings were actually elected to that office by democratic

vote. Kalakaua and his sister Lili`uokalani were well educated, intelligent,

skilled in social graces, and equally at home with Hawaiian traditions and court

ceremony. Above all, they were deeply concerned about the well being of the

Hawaiian people and maintaining the independence of the kingdom. They saw no

reason to relinquish their independence solely to make already rich Americans

richer still. The Hawaiian League's more radical members favored the king's

abdication, and one even proposed assassination. They eventually decided that

the king would remain on the throne, but with his power sharply limited by a new

constitution of their making. Killing him would be a last resort if he refused

to agree. Many Hawaiian League members belonged to a volunteer militia, the

Honolulu Rifles, which was officially in service to the Hawaiian government, but

was secretly the Hawaiian League's military arm.

Kalakaua was compelled to accept a new Cabinet composed of league

members, who presented their constitution to him for his signature at `Iolani

Palace. The reluctant king argued and protested, but finally signed the

document, which became known as the Bayonet Constitution. As one Cabinet member

noted, "Little was left to the imagination of the hesitating and unwilling

sovereign, as to what he might expect in the event of his refusal to comply with

the demands made upon him."

The Bayonet Constitution greatly curtailed the king's power, making him a

mere figurehead. It placed the actual executive power in the hands of the

Cabinet, whose members could no longer be dismissed by the king, only by the

Legislature. Amending this constitution was also the exclusive prerogative of

the Legislature. The Bayonet Constitution's other purpose was to remove the

Native Hawaiian majority's dominance at the polls and in the Legislature. The

righteous reformers were determined to save the Hawaiians from self-government.

The privilege of voting was no longer limited to citizens of the kingdom,

but was extended to foreign residents -- provided they were American or

European. Asians were excluded -- even those who had become naturalized

citizens. The House of Nobles, formerly appointed by the king, would now be

elected, and voters and candidates for it had to meet a high property ownership

or income requirement -- which excluded two-thirds of the native Hawaiian

voters. While they could still vote for the House of Representatives, to do so

they had to swear to uphold the Bayonet Constitution.

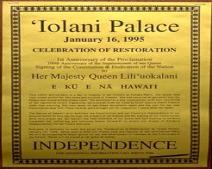

In 1889, there was an uprising of the native islanders against the constitution, which had been forced on King Kalakaua two years earlier. `The last King of Hawaii, King David Kalakaua, built Iolani Palace. The seat of government of the Kingdom of Hawaii, `Iolani Palace had electricity and telephones installed several years before the White House.

The Palace remained a

royal residence until Queen

Lili`uokalani, the King's sister and successor, was deposed and

the Hawaiian monarchy overthrown in January 1893. The queen was imprisoned in

the Palace for eight months in 1895 by the unlawful Provisional Government,

charged with treason for attempting to restore Hawaii’s sovereignty. The

Palace served as capitol of the Provisional Government, Republic, and Territory

in the State of Hawaii. At that time the Palace was vacated and restoration

begun. It is now a museum under the direction of the Friends of `Iolani Palace,

who continue restoration efforts. (`Iolani Palace continues to be a focal point

in efforts to restore Hawaii sovereignty and independence.) The rebellion was

suppressed. With Queen Liliuokalani

on the throne, the Americans formed a Committee of Safety and declared the

monarchy ended. Shortly, after the Republic of Hawaii was established.

On

August 12, 1898, a treaty of annexation was negotiated with the United States

and a formal transfer of sovereignty was made with the promise of eventual

statehood. However, the fact was ignored that Hawaiians submitted a petition to

the United States Congress with 29,000 signatures, as well as petitions to the

Republic of Hawaii asking that annexation be put to a public vote. Hawaiians

were never permitted to vote on the issue.

In all, three separate Treaties of Annexation were sent to the Congress.

All three failed. In the end, Hawaii was annexed by a joint resolution of the

Congress. But Congress did not have the legal authority to do so, because a

joint resolution of the Congress has no legal standing in a foreign country,

which is what Hawaii remained, even under the provisional government.

Sovereignty

of Hawaii was formally transferred to the United States at ceremonies at `Iolani

Palace on Aug. 12, 1898. Sanford Dole spoke as the newly appointed governor of

the Territory of Hawaii. The Hawaiian anthem, ''Hawaii Pono `I" -- with

words written by King Kalakaua -- was played at the Hawaiian flag was lowered,

and replaced by the American flag and "The Star-Spangled Banner." The

Hawaiian people had lost their land, their monarchy and now their independence.

The American plantation owners were now free of import tariffs; making it a

small matter that the Hawaiian people had lost their independence along the way.

Hawaii

became a territory of the United States in 1900.

The pattern of growth then began to accelerate even more rapidly. Hawaii

remained a territorial possession of the United States for many years. The

military presence illegally begun during the Spanish American war continued to

grow, including the naval base at Pearl Harbor. The plantation families grew

richer and richer, while the original Hawaiian people were marginalized, often

homeless in their own homeland. The animosity between Hawaiians and Americans

exploded into public view during the celebrated Ala Moana rape case, in which

famed lawyer Clarence Darrow argued for the defense. The thin veneer of a

tropical paradise, crafted for the emerging tourist industry, was shattered in

moments by the anger shown on both sides.

Hawaii Becomes a State

In

1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided that the best way to get a reluctant

America into a war with Hitler was to "back door" a war by luring

Japan into an attack against the United States. By cutting off oil exports to

Japan, Roosevelt forced Japan to invade the Dutch East Indies, and by placing

the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl, Roosevelt made an attack at Pearl the mandatory

first move in any military move by Japan in any direction. The U.S. Navy

set up its giant Pacific headquarters at Pearl Harbor and the Army built a huge

garrison at Schofield Barracks.

The

attack on Pearl Harbor marked America's entry into World War II, and Hawaii and

its citizens played a major role in the conflict. The postwar period saw many

rapid changes with the descendants of plantation laborers rising to the highest

prominent in business, labor, and government. Following World War II, Hawaii was

placed on the list of non self-governing territories by the United Nations, with

the United States as trustee, under Article 73. Under Article 73 of the U.N.

charter, the status of a territory can only be changed by a special vote, called

a plebesite, held among the inhabitants of the territory.

That plebiscite is required to have three choices on the ballot. The first choice is to become a part of the trustee nation, in Hawaii's case that meant to become a state. The second choice was to remain a territory. And the third choice, required by article 73 of the UN Charter, was the option for independence. For Hawaii, that meant no longer being a territory of the United States and returning to being an independent sovereign nation. In 1959 Hawaii's plebiscite vote was held, and again, the United States government bent the rules. The plebiscite ballot only had the choice between statehood and remaining a territory. No option for independence appeared on the ballot as was required under the UN charter. Cheated out of their independence yet again, Hawaii proved eager to take on the full responsibilities of statehood. Under the leadership of Hawaii's last delegate to Congress, John A. Burns, the 86th Congress approved statehood and President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill into law on March 18, 1959. Hawaii was admitted as the 50th state of the union on August 21, 1959.

|

"The seal of the state of Hawaii features a grand image of King Kamehameha I, royally dressed and holding his staff, and a classic rendition of Liberty, holding the Hawaiian flag, on either side of a heraldic shield. A Phoenix rises up from native foliage. The date 1959, representing Hawaii's statehood, displays prominently. Wording on the seal reads "State of Hawaii" across the top. On the bottom of the seal is a quote attributed to King Kamehameha III, after a British admiral attempted a takeover in 1843: 'Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono", translated as "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.'" --quote from official Hawaiian state government website

|

|

|

|

Many

years later in 1988, a study by the United States Justice Department concluded

that Congress did not have the authority to annex Hawaii by joint resolution.

The ersatz annexation was a cover for the military occupation of the Hawaiian

Islands for purposes related to the Spanish American war. It was not until on

November 23, 1993, President Clinton signed United States Public Law 103-150,

which not only acknowledged the illegal actions committed by the United States

in the overthrow of the legitimate government of Hawaii, but also that the

Hawaiian people never surrendered their sovereignty.

The

latter is the most important part of United States Public Law 103-150 for it

makes it quite clear that the Hawaiian people never legally ceased to be a

sovereign separate independent nation. There is no argument that can change that

fact. United States Public Law 103-150, despite its polite language, is an

official admission that the government of the United States illegally occupies

the territory of the Hawaiian people. In 1999, the United Nations confirmed that

the plebiscite vote that led to Hawaii's statehood was in violation of article

73 of the United Nations' charter. The Hawaii statehood vote, under treaty then

in effect, was illegal and non-binding. (The same is true of the Alaska

plebiscite).

As

of now, there are things that the Hawaiian people are forced to deal with seeing

that they are a technically a state of the United States. One of the issues is

the destruction of many historic landmarks, such as Walgreen’s purchasing the

Kahiki to demolish it for a new drugstore. The Kahiki Supper Club is listed in

the National Register of Historic Places (1997). The Kahiki is an intact example

of a mid-twentieth century cultural icon, the Polynesian restaurant. Built in

1960-61, it represents the heightened interest in Polynesia following World War

II. Entertainment and leisure activities focusing on or derived from the South

Seas were especially popular during the 1950s and early 1960s. Movies and

television shows featured the Polynesian setting, while hula hoops, luaus,

surfing, and beach music allowed people from coast to coast to celebrate the

South Seas culture.

As

in all debates it is only fair to hear both sides. Walgreen's spokesman Michael

Polzin says, "Walgreen’s

has a policy against destroying historic buildings... The company just doesn't

think the Kahiki makes the cut. This building is unusual, but it's not very

old." The Kahiki is one of many historical landmarks being torn down

because companies from the United States are starting to expand their business

there. Alongside the loss of historical landmarks, there is the fact that the

Hawaiian youth are losing their culture by becoming more Americanized rather

than Hawaiian. Increasingly, Hawaii's venerable traditions are being

replaced by inauthentic recreation of those traditions for European and mainland

tourists.

Bibliographic Sources

The Apology Bill, Public Law 103-150, 103d Congress, Joint Resolution, November 23, 1993.

Bell, Roger, Last Among

Equals: Hawaiian Statehood and American Politics, Honolulu:

University of

Hawaii Press, 1984.

Hannum, Hurst, Autonomy, Sovereignty, and Self-Determination:

and The Accommodation of

Confliction Rights, Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania, 1990.

MacKenzie, Melody Kapilialoha, ed., Native Hawaiian Rights Handbook, Honolulu: Native

Hawaiian Legal

Corporation/Office of Hawaiian

Affairs, 1991.

Additional Reading

Dougherty, Michael. To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian

History. Waimanalo, Hawaii: Island

Style Press, 1992.

Dudden, Arthur Power. The American Pacific: From the Old China

Trade to the Present. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Coffman, Tom. Nation Within: The Story of America's Annexation

of the Nation of Hawaii,

Island Styles Press, 1998.

Hawaiian Statehood on the Web

This

website deals with the reaction of the Hawaiian people on statehood issues:

http://honolulu.miningco.com/citiestowns/alaskahawaii/honolulu/gi/dynamic/of

This website provides a chronology of

important events in Hawaii's quest for

statehood:

http://honolulu.miningco.com/citiestowns/alaskahawaii/honolulu/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm