PHI3800 Lecture 3

The Origins of Beauty: Beauty in

Classical and Medieval Thought

The Beauty Bias: Beauty

and Perceptions of Goodness, Excellence and Competence

Beauty and Perceptions of

Truth

Aesthetic Ramifications of

this Metaphysical View

St. Augustine (A.D. 354 - 430)

Boethius b 480; died at Pavia in

524 or 525

St. Thomas Aquinas (A.D. 1225 1274)

The Spell of Plato (or the spell of

beauty?)

The Origins of Beauty: Beauty in

Classical and Medieval Thought

In Classical Times in Western Culture there was thought to be an affinity (if not an identity) among three concepts: Truth, Goodness and Beauty. This is probably much broader than Western Culture. In all cultures Heroic characters are generally presented as beautiful. Take Western Folktales and Myths as examples. The gods are breathtakingly beautiful (except the comic or monstrous ones). The “Evil Witch” is an ugly old crone while the good fairies are beautiful. Monsters are horrifying and usually the result of moral corruption. So predating Plato there is a tradition to thinking of beauty, goodness and truth as related- signs of one another- perhaps in some mystical way, identical.

More recently, some have suggested that there may be biological hardwiring for this conceptual linkage. Studies have demonstrated that physical attractiveness (or lack thereof) affect our perception of a person’s morality and truthfulness. While this operates largely at the unconscious level, we even have evidence of it happening at the (nearly) conscious level. Scientists have long documented the “Halo Effect”

The halo effect occurs when we allow a person's (or product’s, etc.) perceived positive traits to "spill over" from one area to another or even all other areas of our assessment of the person. This occurs with negative traits as well. In marketing, a halo effect is one where the perceived positive features of a particular item extend to a broader brand. Some have suggested that all Apple products are perceived positively due in part to the success of one or another of their products.

So for instance, pretty people are perceived to be more honest and more dependable. Ugly people are perceived to be more devious or less trustworthy. In 1920, Edward L. Thorndike did a study on the Halo Effect. Soldiers were asked to rate their commanding officers. Thorndike found a high cross-correlation between all positive and all negative traits. Evidently, we tend not to think of each other in mixed terms. We tend to view individuals as generally “good” or “bad” across categories and these include appearance, morality, and intelligence.

In the 1950s, Solomon Asch also performed research in this area. Asch found that good-looking schoolchildren are perceived to be smarter, even when no objective evidence is given. This has been shown to be true of good-looking people in general. An interesting question arises however, as to whether what is thought to be “good looking” in purely culturally relative or confined to certain cross-cultural regularities.

The Beauty Bias:

Beauty and Perceptions of Goodness, Excellence and Competence

This is related to another well documented phenomenon- The Beauty Bias:

We tend to pay more attention to good-looking people. Eye-tracking research has shown that both men and women spend more time looking at beautiful women than they do looking at less attractive women (beautiful as defined by cultural norms). Babies as young as 8-months-old will stare at an attractive female face longer than they will at an average-looking or unattractive female face. Here race did not make a difference. Nevertheless, certain human traits appear to be universally recognized as beautiful:

1. symmetry (bilateral, not radial 😊)

2. regularity in the shape and size of the features

3. smooth skin

4. big eyes

5. thick lips

Evolutionary psychologists have suggested that men have evolved to select for these featured as they are associated with health and reproductive fitness. The lack of bilateral symmetry might be an effective indicator of defective genes. “Hour-glass figure” may indicate enhanced fertility. In other words, our ancestors who began to select for these features tended to have more successful offspring. If so, then these preferences would have become “hardwired” “bottom-up” preferences and proliferated throughout our species. Arguably, those of our ancestors who did NOT select for these would not have reproduced as successfully. Note these “associations” may go on at a very low level of cognition or indeed be completely affective.

Nancy Etcoff, author of Survival of the Prettiest[1], claims that women’s responses are more cognitively complex. Etcoff claims that women stare at beautiful female faces out of aesthetic appreciation, to look for potential tips, and to monitor a beautiful woman could be a rival.

Deborah L. Rhode in The Beauty Bias: The Injustice of Appearance in Life and Law[2] suggests that social, market, and media forces that have contributed to appearance-related biases and social problems, as well must be addressed when attempting to confront them. Rhode claims appearance-related bias infringes fundamental rights, compromises merit principles, reinforces debilitating stereotypes, and compounds the disadvantages of race, class, and gender. At the time of her writing, only one state and a half dozen localities explicitly prohibit such discrimination. She claims that while our prejudices run deep, we can do far more to promote realistic and healthy images of attractiveness and combat this form of unjust discrimination.

So here we see an important divide with respect to beauty: Are our aesthetics preferences (which we clearly have and which affect our judgements)…

1) Bottom Up?

2) Top Down?

3) A little bit of both?

By “bottom-up” cognitive science researchers have in mind cognitive processes which are to some extent “hardwired.” They are largely the product of our biology and genetic inheritance. Evidence that a process is bottom-up would be if it is universal or nearly universal across the species, that is, cross-cultural and if the process manifests itself very early on in the biological development of humans. Gestalt Principles of perception would be an example. By top-down cog sci researchers have in mind processes which are culturally acquired. Evidence that a cognitive process is top down would be if it is not universal or cross culturally prevalent and if it is acquired later in the biological development of human beings. Language use would be an example of a top-down cognitive process. (Though the ability to acquire and use language may be “bottom up.”0

Of course, until we nail down precisely what we mean by “aesthetic preference” and “aesthetic experience” it's not clear what set of processes we're talking about and therefore it would be difficult to determine whether they are exclusively top-down, exclusively bottom-up, or a basket of related, but distinct processes of both kinds. Nevertheless, the answer to these questions will determine what and how much we can do to combat the “beauty bias.” Education campaigns and legislation against fatty food or sugary drinks can only do so much to combat obesity given that these preferences are not to-down, rather bottom-up.

Beauty and Perceptions of

Truth

But beauty also seems to have a very old conceptual tie to truth and rationality. Ockham’s famous Principle of Parsimony (Ockham’s Razor) admonishes us not to postulate entities beyond necessity. More broadly, the principle of parsimony implies that the simpler (more elegant/prettier) explanation is more likely to be true. This is arguably an aesthetic preference. Why should we assume the world is best described by the prettiest theories? Why should we not presume that that the ugly theory and complicated theory describes reality? Even today scientists today seek beautiful (elegant) theories. In his book Beauty and Revolution in Science, James McAllister quotes Scientist Sor George Thomson:

“One can always make a theory, many theories, to account for known facts, occasionally to predict new ones. The test is aesthetic”

McAllister continues on to write:

“It is a mysterious thing in fact how something which looks attractive may have a better chance of being true than something which looks ugly…so often, in fact, it turns out that the more attractive possibility is the true one”

In his Dreams of a Final Theory, Steven Weinberg defines a beautiful theory as possessing “simplicity,” a sense of inevitability or logical completeness, and symmetry. Weinberg writes: completeness is the “beauty of everything fitting together, of nothing being changeable, of logical rigidity”

As Einstein said of general relativity, “to modify it without destroying the whole structure seems to be impossible”

W.L Bragg writes in “Science and Christian Belief” Christian belief (page 99)

“When one has sought long for the clue to a secret of nature, and is rewarded by grasping some part of the answer, it comes as a blinding flash of revelation: it comes as something new, more simple and at the same time more aesthetically satisfying than anything that one would have created in one's own mind. This conviction is of something revealed, not something imagined.

Roger Penrose writing in Scientific American, suggests that “Aesthetic qualities are important in science, and necessary, I think, for great science.”

And, perhaps my favorite of the bunch: Morris Kline, writes in Mathematics in Western Culture (page 470)

“Much research for new proofs of theorems already correctly established is undertaken simply because the existing proofs have no aesthetic appeal. There are mathematical demonstrations that are merely convincing; to use a phrase of the famous mathematical physicist, Lord Rayleigh, they ‘command ascent.’ There are other proofs ‘which woo and charm the intellect. They evoke delight and an overpowering desire to say, Amen, Amen.’ An elegantly executed proof is a poem in all but the form in which it is written.

As we shall see, Plato talks about beauty possessing a “unity.” Aristotle likewise talks about “organic unity” which was a good-making aesthetic feature of art, of nature and thus of truthful descriptions of nature.

However this view is not universally accepted. I would venture to bet that many (perhaps most) scientists would claim that there is no direct connection between beauty and truth. Further, even among those who assert such a connection, there are very few who would claim that a person’s attractiveness was in any way a predictor of the person’s morality, intelligence or truthfulness. And I would wholeheartedly concur with this.

And yet…

I remember being in a bookstore one time and looking at the cover of a paperback account of the life and crimes of serial killer Ted Bundy. I recall staring at the photo of the very handsome man, looking for the monster- confident that there had to be some sort of telltale sign- maybe in the eyes-

But why? Why did I believe that there had to be some ugliness there, some visible evidence of his evil corruption? Of course, if you would have asked me “Is it always visually apparent when a person is morally good or morally bad?” I would have said, “Nonsense. Of course not.” But there I was, staring at the photo. Maybe because there is something contradictory about a beautiful evil (ugliness).

What’s my point?

I think we have good reason to suspect that the cognitive association of Goodness, Beauty and Truth is biologically hardwired in us. These are perhaps reenforced and seemingly confirmed by cultural factors as well. Therefore it should not surprise us to find theories arising in the Ancient and Medieval world which purport to establish/ discover the objective nature of these connections.

So Plato formalized the notion common to many (if not all) cultures that Beauty was tied to Truth and to Goodness. Much of Platonic Philosophy deals with distinguishing between appearance and reality. And just as not everything that appears true is true, and not everything that appears good is in fact good, so too…for Plato and those who followed him on this, not everything that appears beautiful is beautiful. For Plato then, Beauty is divorced from “Appearance." That something has a pleasant appearance tells you nothing about whether it is beautiful or not. This understanding of real beauty versus apparent beauty makes its way into the Middle Ages and even early modern times. For instance a “glamour” or “to cast a glamour” was a deceptive spell which can make something that is truly vile appear enticing and attractive. Now of course it's just a trashy magazine. 😊 So for Plato:

Beauty ≠ Pleasant Appearing

Plato makes a similar point about “goodness.” He notes that not everything that tastes good is good (for you). There is an important difference between the cook and the dietician, the beautician and the physical therapist. Plato’s view on beauty is importantly different from the view of beauty that most people have today [i.e. That “X is beautiful.” = “X is visually pleasing (to me).”].[3] For Plato. the wise person. The lover of wisdom, ust distinguish between:

• apparent truth and real truth, and

• apparent goodness and real goodness,

• apparent beauty (glamour) and REAL BEAUTY.

Hence the branches of Philosophy: Epistemology, Ethics and Aesthetics

In the Gorgias, Callicles said that Socrates could not speak persuasively enough to defend himself at trial if he were brought into court on false charges by someone who could speak persuasively. Socrates agrees with him, saying:

“I won’t have anything to say in court…For I will be judged as a doctor would be judged if a pastry chef accused him in front of a jury of children” (521e2-4)

At several places in the dialogue that Socrates compare himself to a doctor, and his practice of philosophy to medical practice. Earlier he had exhorted Polus to answer his questions by saying “Answer, submitting yourself nobly to the argument as to a doctor” (475d7). And he has asked whether he should “struggle with the Athenians so that they will become as good as possible, like a doctor, or be servile and associate with them for their gratification” (521a2-5),

Of course, he is clearly implying that he, in fact, does the former.

For Plato then, Beauty is divorced from “Appearance" just as, sadly, nutrition can be divorced from tasting good. That something has a pleasant appearance tells you nothing about whether it is beautiful or not.

In The Symposium Plato presents his view on the proper way to learn to love beauty:

· Begin at an early age

· First be taught to love one beautiful body (a human body).

· Notice that the first body shares beauty with other beautiful bodies. (provides a basis for loving all beautiful bodies)

· Realize that the beauty of souls is superior to the beauty of bodies.

o (After the physical is transcended, then the second spiritual stage begins.)

· Learn to love beautiful practices and customs.

· Recognize their common beauty. (form)

· Recognize the beauty in the various kinds of knowledge.

· Experience “Beauty” itself (not embodied in anything, physical or spiritual.)

Note: Knowledge rises through increasingly abstract levels and culminates in the ultimate abstraction: The Form of Beauty.

When we truly know what we love, what we have been loving all along, we know it to be the pure abstract Form of Beauty. It was this Form that was shining through all the lower objects and ideas along the way. While we call other things beautiful, it is only because the Form of Beauty shines through them that we love and value them (and should love and value them). Therefore, it is the Form of Beauty that is the source of value and prompts our admiration. And the proper response to genuine beauty is love. Further, love is misdirected if it is directed at anything else.

Plato's treatment of beauty here is an example of his Theory of the Forms. I will only sketch his theory here.

Borrowing heavily from Pythagoras, Plato argues that we have a priori knowledge of pure forms, immaterial, eternal mind-independent realities which nevertheless, govern and direct the world of our appearances. Indeed, the objects of our appearances, the mutable particular physical objects which we see and with which we interact could not exist were it not for the forms.

Thus, for Plato, the forms are the “most real” aspect of reality because these objects are more lasting, (i.e. more real) And more powerful than anything found in the world of appearances. Further, the only reasons particular things are the particular things that they are is in virtue of embodying the form that they do. Thus the very existence of particulars is itself parasitic on (less real than) the Forms. Think of it this way; there could be no pictures of cars unless there were a car to picture. The picture of a car is ontologically dependent upon the car, but not the other way around. Likewise, this means that pictures of cats are ontologically dependent (and less “real”) than are cats. And the cats themselves are ontologically dependent upon “Form of Cat.” (Existence cannot precede Essence.)

Except for God maybe, and existentialists 😊

Forms are themselves arranged into a hierarchy, the arch Form being “the Form of the Good.” Plato then is a metaphysical dualist. That is, he believes that in order to explain reality one must appeal to two radically different sort of substances, in this case, material substance and immaterial substance.

Aesthetic Ramifications of

this Metaphysical View:

When we recognize that something is beautiful we do so because we recognize that it participates in the eternal form of beauty. Beauty names a transcendent object which does not exist in the world of sense objects, but of which beautiful objects are mere imperfect copies. Further, since whether an object participates in the form of beauty or not is an objective relation with no logically necessary consequences for perception, it follows that judgements about whether an object is beautiful or not are not mere subjective reports, but rather claims about objective states of affairs. They cannot be based solely on sensual appeal and are subject to revision and correction.

Nevertheless, “recognizing” beauty, like recognizing truth seems to be a phenomenological revelation or epiphany. An Intuition- a non-evidentially grounded certainty of an objective truth. Consider the logical intuition:

All A is B

All B is C

Therefore?

All A is C

… but how do you know?

In a similar way, I judge (am phenomenologically certain that) “X is beautiful. “ Or “X is more beautiful than Y.”

…but how do you know?

Under the influence of Plato, classical philosophy meditated extensively on what was termed “the transcendentals.” These are considered to the properties of Being and consequently of all beings. Specifically these are The True, The Good, and The Beautiful (and perhaps others such as Unity). Classical philosophy regarded these transcendentals as qualities of “Being-as-such.” Truth is Being as knowable; Goodness is Being as lovable; and Beauty is being as admirable, attractive, and desirable.

Now, it is common for us today to think of “truth” as a property that applies only to propositions or sentences. Similarly we think the adjective “true” is an adjective that only applies to propositions or sentences, etc. But a more classical understanding of “truth” holds that true is a property that describes things. Things are true, in the sense of a “true friend” or a “true love” or a “true blade.” Under this older understanding of true, to say a thing is true is to say that it approaches its own perfection as the sort of thing that it is (that it “be”). For instance, a true friend is a friend who exemplifies friendship most fully, a friend who “be” friendship fully. To the extent that your friend is/be a friend, be as a friend, he exemplifies the ideal of friendship. And the more fully he “be” a friend, the more fully he exemplifies this ideal of friendship. Thus, to the extent something is true, it has a greater degree of reality as the sort of thing that it is. Things are true to the extent that they “be,” and they “be” (exist) to the extent that they are true. But note further, this means that to that very same extent, they are unimpaired and thus they are true, good and beautiful.

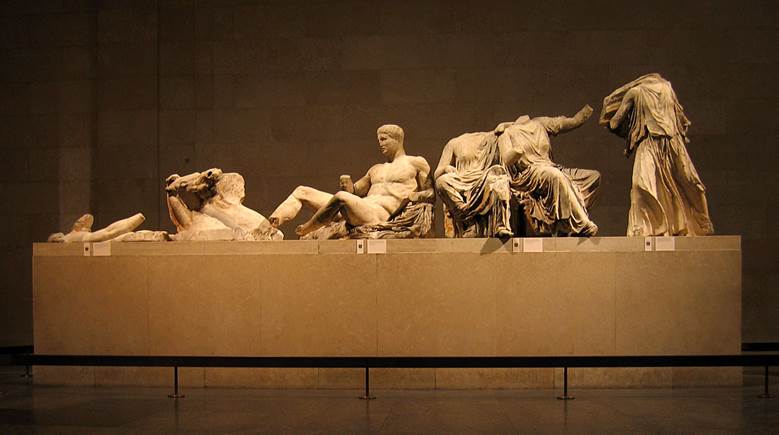

John Keats, after spending several hours in the contemplation of the Elgin Marbles, a collection of Ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon and other structures from the Acropolis of Athens, composed his famous “Ode to a Grecian Urn.” He conclude with perhaps his most well-know line:

“Beauty is truth, and truth

beauty. This is all you know on earth, and all you need to know.”

Now this has admittedly been some somewhat heavy metaphysical theorizing , but it underscores the seriousness with which the Classical World regarded beauty.

Two sorts of beautiful things:

Plato does note some common characteristics of beautiful things of the world of sense, (though somewhat ambivalently) and suggests that there are properties that all beautiful things have in common.

Simple beautiful things. (e.g., pure tones and single colors),

Complex beautiful things.

The simple things have unity owing to their simplicity, while complex things have measure and proportion of parts, which are also a form of unity. The many can be “one.” It is not clear whether Plato means to identify beauty and unity. But it is at least a discoverable fact (allegedly) that all beautiful things are unified. Plato seems to believe that beauty is a simple, un-analyze-able property, which means that the term cannot be defined at all. If so, then we can learn only by direct experience. Nevertheless, Plato’s emphasis on measure and proportion set an important precedent for all subsequent philosophers.

An Important result of the theory of Plato was the establishment of the notion of contemplation as a central idea in the theory of beauty and, consequently, in the theory of aesthetic experience. This suggests a kind of meditation necessary to bring us to an awareness of some non-sensuous entity. Something of the Platonic sense of “Contemplation” remains in modern aesthetic theories. American philosopher George Dickie (1926 – 2020) argues that this is regrettable and is responsible for the solemn and pompous attitude toward art and beauty that some persons display. (Think of the solemnity of most contemporary art museums even today.) Dickie points out that many of our experiences of art and nature are NOT contemplative in Plato’s sense[4]. He notes that art can be playful, boisterous, irreverent, etc.

Some thought of beauty as an object that does not exist in the world of sense. (Neo-Platonists) Others identified beauty with measure and proportion as we find it in our sensuous experience. Nevertheless, this “Objectivist” account of Beauty hung on for quite some time. Eventually it lost ground to its ancient rival, Subjectivism.

“De gustibus non disputandum est.”

St. Augustine (A.D. 354 - 430)

St. Augustine was an important Chirstian philosopher and theologian. His work reflects not only the early direction of the Christian Church, but the phenomenal influence of Plato and Neo-Platonists. Augustine is considered to have straddled the Ancient and Medieval Epocs and to have perpetuated the Platonic theory of beauty as well as other Platonic doctrines within the orthodox Christian World View. In the opening chapters of his On Christian Doctrine, Augustine argues that everything that exists can be divided into three groups:

1. things to be enjoyed (make us blessed)

2. things to be used (sustain us as we move toward blessedness)

3. things to be enjoyed and used.

But we must be careful not to confuse them. Before his conversion, St. Augustine once asked his friends:

“Do we love anything but the beautiful? What then is the beautiful? And what is beauty? What is it that allures and unites us to the things we love? For unless there were a grace and beauty in them, they could not possibly attract us to them” (Confessions, Bk. IV, ch. 13).

After his conversion, Augustine regretted becoming enthralled with beautiful things rather than the “true source” of Beauty. When so entranced by the things (particulars), the beautiful things became diversions from the path to God.

“Belatedly I loved Thee, O Beauty, so ancient and so new, belatedly I loved Thee. For see, Thou wast within and I was without, and I sought thee out there. Unlovely, I rushed heedlessly among the lovely things Thou hast made. Thou wast with me, but I was not with Thee. These things kept me far from Thee; even though they were not at all unless they were in Thee. (Bk. X, ch. 27)

So for Augustine, the value of anything, thing’s of beauty included, was its usefulness in leading us to the REAL thing of value, indeed the bestower of value, God. (Note how very similar this is in outline and in spirit to Plato.) Thus God alone is to be enjoyed/loved. All else is only to be used. Augustine notes that all things of value issue from the source of values –not Plato’s Form of the Good in this case, but rather “God.” (Somewhat close enough I suppose. 😊)

To enjoy something is to cling to it with love for its own sake. To use something, however, is to employ it in obtaining that which you love, provided that it is worthy of your love. An illicit use (enjoying what is only to be used) should be called rather a waste or an abuse. If we enjoy (and cling to with love) those things which should be used, our course (to blessedness) will be impeded and sometimes deflected.

He writes:

“Suppose we were wanderers who could not live in blessedness except at home, miserable in our wandering and desiring to end it and to return to our native country. We would need vehicles for land and sea which could be used to help us to reach our homeland, which is to be enjoyed. But if the amenities of the journey and the motion of the vehicles itself delighted us, and we were led to enjoy those things which we should use, we should not wish to end our journey quickly, and entangled in a perverse sweetness, we should be alienated from our country, whose sweetness would make us blessed.

The (only) things which are to be (genuinely) enjoyed are the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, a single Trinity, (a certain supreme thing common to all who enjoy it).

On Christian Doctrine VI

“I feel that I have done nothing but wish to speak”

This is the ineffable nature of the Divine. But even calling the experience of God ineffable is problematic, as Augustine points out, because you are still “effing.”

“This contradiction is to be passed over in silence rather than resolved verbally.”

On Christian Doctrine XXXV

“The end of the Law and of all the sacred Scriptures is the love of a Being which is to be enjoyed. (and one might add, of all things that are to be used- Art/Beauty)

These next three I put in just because I thought they show a more ecumenical side to Augustine.

On Christian Doctrine XXXVI

“Whoever, therefore, thinks that he understands the divine Scriptures or any part of them so that it does not build the double love of God and of our neighbor does not understand it at all.”

“Whoever finds a lesson there useful to the building of charity, even though he has not said what the author may be shown to have intended in that place, has not been deceived, nor is he lying in any way.”

“However, as I began to explain, if he is deceived in an interpretation which builds up charity, which is the end of the commandments, he is deceived in the same way as a man who leaves a road by mistake but passes through a field to the same place toward which the road itself leads. But he is to be corrected and shown that it is more useful not to leave the road, lest the habit of deviating force him to take a crossroad or a perverse way.”

“Indeed, if faith staggers, charity itself languishes. And if anyone should fall from faith, it follows that he falls also from charity, for a man cannot love that which he does not believe to exist. On the other hand, a man who both believes and loves, by doing well and by obeying the rules of good customs, may bring it about that he may hope to arrive at that which he loves. Thus there are these three things for which all knowledge and prophecy struggle: faith, hope, and charity.”

“Between temporal and eternal things there is this difference: a temporal thing is loved more before we have it, and it begins to grow worthless when we gain it, for it does not satisfy the soul, whose true and certain rest is eternity; but the eternal is more ardently loved when it is acquired than when it is merely desired.”

As we shall see, Aquinas defines beauty as that which calms the desire by being seen or known.

The Augustine corpus presents a “theology of beauty” characterized by an objective notion apparent to the senses and a subjective notion that attracts and is desirable. God, then, is the source of all truth, beauty, and goodness and is “seen” by the faithful who are pure in heart.

Although Augustine’s treatise De Pulchro et Apto is lost, Augustine alludes to the treatise’s purpose when he realizes, after contemplating the nature of beauty, a distinction between that which is beautiful in itself and that which is beautiful in relationship to another object.

What then is beautiful, and what is beauty? When considering beauty inherent to an object and apparent to the senses, Augustine defines beauty in terms of number, form, unity, and order. Beauty for Augustine is not a simplistic either/or. Rather, Augustine nuances beauty by recognizing the complexities of corporeal beauty in relationship to the fall of humanity and thus contends that corporeal beauty exists in various degrees depending upon the extent to which the object possesses number, form, unity, and order. A being that possesses these qualities to a greater or lesser degree is either more or less beautiful.

What then of the ugly? Does the ugly think possess beauty as well? When making these judgments, according to Augustine, we must consider the part in light of the whole if we are to make a true judgment. To do otherwise is to cling only “to a part, i.e., the ugly.” So then, in one sense, every corporeal thing is beautiful to some degree because it exists. Yet every corporeal thing is ugly to some degree because of what it lacks (sin).

Is this then all that beauty amounts to—the extent to which these objective criteria are inherent within an object? Augustine does not succumb to the fallacy of reductionism when assessing the beauty of an object. Rather, Augustine sees an incorporeal or supreme beauty, namely God, from which corporeal beauty has its meaning and existence.

“But what is it that I love in loving Thee? Not physical beauty, nor the splendor of time, nor the radiance of the light—so pleasant to our eyes—nor the sweet melodies of the various kinds of songs, nor the fragrant smell of flowers and ointments and spices; not manna and honey, not the limbs embraced in physical love—it is not these I love when I love my God.

“Yet it is true that I love a certain kind of light and sound and fragrance and food and embrace in loving my God, who is the Light and Sound and Fragrance and Food and Embracement of my inner man—where that Light shines into my soul which no place can contain, where time does not snatch away the lovely Sound, where no breeze disperses the sweet Fragrance, where no eating diminishes the Food there provided, and where there is an Embrace that no satiety comes to sunder. This is what I love, when I love my God. (Bk. X, ch. 6)

Boethius b 480; died at Pavia in

524 or 525

He wrote The Consolation of Philosophy when imprisoned, before being executed by King Theodoric. He was a scholar who tradition holds was a martyr for the Christian faith. Curiously though, his most famous work, The Consolation of Philosophy, makes no mention nor use of Christian doctrine, but relies on "natural reason" alone. We see here in his condemnation of “poetry” the old Platonic criticism of the mimetic arts in general, but not a criticism of genuine (intellectual) beauty, for the latter, in is good (healthful) and true. He narrates a vision of being attended to in his jail cell by the muses of poetry and then being visited my Lady Philosophy

“When she saw that the Muses of poetry were present by my couch giving words to my lamenting, she was stirred a while; her eyes flashed fiercely as she said: “Who has suffered these seducing mummers to approach this sick man? Never have they nursed his sorrowings with any remedies, but rather fostered them with poisonous sweets. These are they who stifle the fruit-bearing harvest of reason with the barren briars of the passions; they do not free the minds of men from disease but accustom them thereto.

“I would think it less grievous if your allurements drew away from me some common man like those of the vulgar herd, seeing that in such a one my labors would be harmed not at all. But this man has been nurtured in the lore of Eleatics and Academics. Away with you, sirens, seductive even to perdition, and leave him to my Muses to be cared for and healed!”

We see what will become an institutional censoring Art and all things “beautiful”, very similar to what Plato prescribed in The Republic, and coinciding with the advice of Augustine, should the work fall short of the “test” of true beauty. Also culturally inherited is Plato suspicion of Theatre as deliberate deception. And was is false and injurious cannot (metaphysically) be beautiful.

St. Thomas Aquinas (A.D. 1225

1274)

Aquinas was heavily Influenced by the philosophy of Aristotle (384 322 B.C.), with which he supplemented and transformed Plato's influence on Christian thinkers. Aristotle had rejected the Platonic view that the Forms transcend the world of experience and exist in their own distinct realm. Rather, for Aristotle, Forms are embodied in nature as we experience it and have no independent existence. There are not two worlds (as Plato held), but only one according to Aristotle, and it is perfectly intelligible. Therefore, there is a basis for an interest in closely examining the world of phenomena of both nature and art.

St. Thomas Aquinas’ philosophy expresses this empirical mindset, so his conception of Beauty was not an other-worldly one. He defines "beauty" as:

a) "that which pleases when seen.”

b) "the beautiful is that which calms the desire, by being seen or known."

Thus beauty is related to desire.

Acquinas goes on to isolate the properties of the objects that do in fact please and calm desire by being seen or known. We must not pass over too quickly the notion of ‘being seen’ here. He probably means it as associated with the activity of contemplation and understanding. Thus it is not merely a function of perception and the body, but a function of the mind and thus the rational soul.

Jacques Maritain offers some helpful explanation:

“Beauty is essentially the object of intelligence, for what knows in the full meaning of the word is the mind, which alone is open to the infinity of being. The natural site of beauty is the intelligible world: thence it descends.

Rember that, while it is not clear whether Aristotle believed human beings had immortal, immaterial souls or not, Aquinas interprets him in such a way. Aquinas of course explicitly states that we do have immaterial souls. Some of our cognitive functions can be accounted for merely in terms of bodily functions such as sensations, but others, Acquinas argues, can only be accounted for by the rational soul which is itself non-corporeal. While it's true that Aristotle was a “materialist” of sorts we must attribute to him materialism understood in post-Cartesian terms as “res extensa.” Aristotle’s notion of “matter” would not necessarily preclude possibility of non-corporeal matter. For both Aristotle and Aquinas, matter is simply the ability to take on form. It is potentiality awaiting actuality. So for Aquinas, Angels are perfectly possible things. in fact he argues at length that they are real. (He is “The Angelic Doctor” after all.) They are material though, in the sense they are hylomorphic combinations of form and matter/ actuality and potentiality, but they are also our non-corporeal.

Maritain continues:

“But it falls in a way within the grasp of the senses, since the senses in the case of man serve the mind and can themselves rejoice in knowing: ‘the beautiful relates only to sight and hearing of all senses, because these two are maxime cognoscitivi’(Maritain, 23).

The knower (or beholder) receives data from the sensible world through the senses. But the senses do not on their own recognize the form of the object, rather the form must be abstracted by the intellect. Thus the senses are not what recognize an object as beautiful. The mind is responsible for recognizing the beauty of a given object.

Consequently, knowledge has two aspects: passive and active.

1) The passive aspect receives data from extra-mental reality.

2) The active aspect gives the abstracted forms new existence in the mind of the knower.

The details of this process are not relevant here; it is mainly important to see that the form of the object in reality begins then to exist in the mind of the knower. Since beauty, for Thomas, is caused by the form of the object, then this process explains how the apprehension of beauty is the result of cognition. Acquinas is stressing the cognitive (knowing) aspect of the experience of beauty.

According to Aquinas then, in the experience of beauty, the mind grasps a Form that is embodied in the object of the experience. Mind grasps or abstracts the form that causes an object to be what it is. Thus the mind gains knowledge through the experience of beauty.

It is probably worth explicitly stating that while Aquinas is an Empiricist, he's not a Locken Empiricist. In other words, he doesn't think that we come to our understanding of general terms like “man” through induction. For Locke, he would say that we observe:

1.) That that man's mortal. And

2.) That man's mortal. And

3.) That man's mortal

And thus conclude:

All men are mortal (probably).

But this only gives us an inductive inference with the likelihood of being true. That's not how it worked for Aristotle or for Aquinas however. They believed that when the active intellect abstracts the form of humanity from humans, and truly comes to understand what the essence of human is, one has come to know a timeless and eternal reality. These forms are no less real and no less eternal than they were for Plato. The only difference is that for Aristotle and for Aquinas, the forms exist in the individual humans, not off in Plato's heaven. This is why we can say that all men are mortal is a necessarily true, universal claim.

The syllogism

All men are mortal.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore

Socrates is mortal.

is often offered as an example of a valid syllogism and of course it is. What is less often noted is that it is an example of precisely how science should proceed according to Aristotle and Aquinas. One begins with a necessarily true claim about the essence of a species, followed by another necessarily true claim about the essence of an individual and then concludes is a necessarily true claim which follows from their union. Thus Socrates “mortality” is “caused” by his form. This is what was meant by Formal Causality in Aristotelian, Thomistic and Scholastic thought.

Acquinas identifies three features of beautiful things:

1.) perfection or unimpairedness

2.) proportion or harmony

3.) brightness or clarity (Here I think he has in mind the degree to which they yield to being “seen.”)

These conditions of beauty appear to be objective features of the object in question.

But he also said that beautiful things

1) Calm the desires by being seen or known

He combines both objective and subjective aspects. Note that the idea of pleasing is a subjective element. (Being pleased is a property of a subject.) Likewise, the calming of the desire happened within the subject of the beauty experience. So he appears to combines both objective and subjective aspects. This represents a significant step away from the objective Platonic conception of beauty toward a subjective conception.

But if the grasping of a Form is the only thing involved in the cognition of beauty, this suggests that there may be no single Form or property of beauty per se that it is common to all beautiful things, the possession of which makes them beautiful. In other words, contra Plato, the object of such a cognitive experience is NOT the Form of Beauty.

Ficino was an Italian Renaissance Neo-Platonist philosopher who translated into Latin the works of Plato and Plotinus making these more widely accessible during the Renaissance. He was fascinated with classical mythology and magic and in his own work, promoted a synthesis of Neo-Platonic thought with the doctrines of Christianity. For Ficino, the visual arts were especially important. Their function was to remind the soul of its origin in the divine world by creating, through art, resemblances to that world. Ficino's insistence on the importance of this with respect to painting has been credited with raising the status of the painter in Florentine society to that nearer the poet (rather than that of the carpenter, where it had been previously).

“Plato asserted that in all things there is one truth, that is the light of the One itself, the light of Deity, which is poured into all minds and forms, presenting the forms to the minds and joining the minds to the forms. Whoever wishes to profess the study of Plato should therefore honour the one truth, which is the single ray of the one Deity.

“This ray passes through angels, souls, the heavens and other bodies ... its splendour shines in every individual thing according to its nature and is called grace and beauty; and where it shines more clearly, it especially attracts the man who is watching, stimulates him who thinks, and catches and possesses him who draws near to it. This ray compels him to revere its splendour more than all else, as if it were a divine spirit, and, once his former nature has been cast aside, to strive for nothing else but to become this splendour.

The image of painting is Ficino's most frequent metaphor. In the Platonic Theology he describes the first impulse in the creation of a painting. He writes:

“The whole field appeared in a single moment to Apelles and aroused in him the desire to paint.‘

(Note the echo of Plato’s assertion that artistic creativity comes as a sort of “Divine Madness” and not an acquired, rational, skill.)

Incidentally, Ficino's was on close terms with the Pollaiuolo brothers and closely directed the painting of Botticelli's Primavera.

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445 – 1510) works embody the spirit of the Renaissance. By this point in Western history, traditional Medieval Christianity and its renunciation of the worldly (pleasures, interests, concerns) had lost much of its appeal, perhaps due in part to the disappointment of the 1st millennium and later the Crusades. The Ancient pagan ideals of beauty and “the good life” began to reassert themselves. Consider Primavera; this is a thoroughly Pagan picture, an exuberant revival of embodied natural forces in an era of total control by the Church. The style is reminiscent classical styles of art, similar is style to roman frescos.

But Botticelli was permitted to paint such images (when previous artists could not) because of Ficino's philosophy/theology. Ficino argues that the "celestial Venus" and the Virgin Mary were expressions of "Divine Love." He spoke of “emanations” from (of?) God into the Noetic world. With this philosophy in mind, Botticelli’s pagan gods are seen in a new, sanctified context. The pagan gods are representations of the ideals of Christianity. Thus Ficino seemed to offer the perfect solution to the dilemma of the Renaissance.

But later in life, Botticelli came under the influence of Girolamo Savonarola. In 1494 Savonarola began preaching for religious reform and denouncing the reborn pagan ideals. He developed a sizable following among the ordinary Florentines. Once under his influence the effect on Botticelli's artwork was enormous. Fearful of going to hell for his sin, Botticelli destroyed many of his pagan pieces. Thereafter, his works reflect obvious moralizing.

The Calumny of Apelles

Sandro Botticelli

1494–95 AD

That year he abandoned painting altogether.

Interestingly, the year 1500 marks the date at which Savonarola declared that the world would come to an end, and the God’s “Last Judgment” would occur. Savonarola himself never saw his prediction fail. In 1498, he was tried for heresy and burned alive in the public square of Florence, possibly on trumped up charges.

The Spell of Plato (or the spell of

beauty?)

Even with St. Thomas’ (small) move away from the Metaphysical Explanation of Beauty, Western thought was slow to give it up entirely. Even into contemporary times we see those who suppose “beauty” is a window to a different “higher” realm of reality. It punctuates the mundane they tell us and brings us into a direct acquaintance with higher levels of reality. Romantic philosopher and theologian Jakob Friedrich Fries (1773 – 1843) suggested that in aesthetic experience we've received inclinations of the spiritual divine realm. We can hear echoes of this in the transcendentalism of the American romantics of the 19th century. Even in the 20th century writers like Mircea Eliade who’s understanding of religion centers on his concept of hierophany (manifestation of the Sacred) argued that sacred spaces and objects can bring us to an awareness of the divine.

However, more common these days is an out and out reject of any “spooky” accounts of beauty. Contemporary thinkers are more likely to agree with philosopher like George Santiana who claims that beauty does not arise from anything divine, but from naturalistic psychological processes. Santayana objected to the role of God in aesthetics in the metaphysical sense, but accepts the use of God as metaphor. Beauty is a human experience, based on the senses. How this view eclipsed the former will be precisely what we will be examining next.