Research Projects – Conservation Lessons

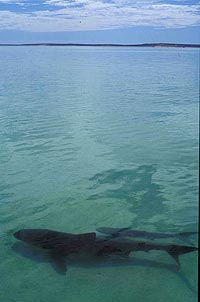

The Importance of Tiger Sharks and Risk Effects

Bay. Tiger sharks play an important role in

the ecosystem by inducing behavioral

changes in their prey. These "risk effects"

of tiger sharks probably are more important

to the dynamics of the ecosystem than the

number of prey tiger sharks kill. The loss of

tiger sharks from Shark Bay would probably

cause major changes to the bay. We should

be concerned because tiger sharks have

been declining in some areas of the world.

The large fish following the tiger shark is a

cobia - a bony fish that is often found

following large predators like tiger sharks.

Populations of large sharks have declined dramatically, and continue to decline, in most of the world's oceans. Our studies in Shark Bay have shown that tiger sharks are very important for determining the distribution and abundance of many of their prey species and probably affect the very base of the ecosystem - the seagrass - through behavioral changes they cause in their prey (like green turtles and dugongs). Therefore, it is important that tiger sharks are maintained in Shark Bay and other seagrass ecosystems where they naturally occur. In fact, recent observations in Bermuda (Atlantic Ocean), where tiger sharks have declined dramatically, suggest that turtle populations may be growing so rapidly that they are causing seagrasses to decline! While there are many conservation efforts aimed at restoring populations of turtles and other large herbivores, our work in Shark Bay strongly suggests that we also need to restore populations of top predators (like tiger sharks) at the same time (or soon after) to avoid potential unintended negative consequences of management. Indeed, the restoration of marine herbivores in the absence of predators could cause changes to marine ecosystem that mirror those that occurred on land when wolves and other large predators disappeared. Herbivores were then able to feed free from the risk of predation and negatively impacted plant communities and the species that relied on them (like birds).

Like our studies of tiger sharks and their prey, studies of wolves and other large land predators suggest that many of the changes that occur in ecosystems are due to changes in how prey change their behavior when predators disappear ("fear-released systems"). Therefore, we not only need to ensure that predators are still around in the oceans but that they are found in numbers high enough to maintain their full ecological role (including changes in the behavior of their prey).

Human Disturbance Can Affect Habitats That Look Like They Are Protected

sharks can be used to help us understand

how they might be influenced by boat

disturbance. They might actually abandon

habitats where boats are less common if

they feel like it is an area where they might

be easily cornered by a predator.

Many recent studies have shown that animals often respond to human disturbance in a similar manner to their natural predators. This includes avoiding areas where human disturbance is frequent, fleeing from disturbance, and incurring foraging and reproductive costs. For example, dugongs and turtles faced with disturbance from boats flee to deep habitats and some bottlenose dolphins abandon areas where there is chronic boat traffic.

Our work on the factors influencing the responses of particular prey species to the risk from tiger sharks shows that we can't assume that areas of high predator abundance (or by extension boat traffic) are necessarily the areas that these prey consider the most dangerous. For example, dugongs, dolphins, and green turtles in good condition move out of the interior areas of banks and into the edges of banks when shark abundance increases - even though there are more sharks along the edge. They do this because it is easier to escape from a tiger shark they do see in the edges (see our Escape Tactics research page for more information). This suggests that marine animals may avoid areas where there is relatively little disturbance if they perceive it as dangerous if they do encounter what they believe might be a predator. This means that a specific knowledge of what habitats animals perceive as safe and dangerous is necessary for creating low disturbance refuges and it may be necessary to manage the overall level of disturbance more than the spatial pattern of disturbance.

Conservation: Relevant Publications

- Heithaus, M. R., A. Frid, J. Vaudo, B. Worm, and A. J. Wirsing. in press. Unraveling the ecological importance of elasmobranchs. In: J. C. Carrier, M. R. Heithaus, and J. A. Musick (eds). Sharks and their relatives II: Biodiversity, adaptive physiology, and conservation. CRC Press.

- Heithaus, M. R., A. Frid, A. J. Wirsing, and B. Worm. 2008. Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 23: 202-210.

- Heithaus, M. R. A. J. Wirsing, A. Frid, and L. M. Dill. 2007. Species interactions and marine conservation: lessons from an undisturbed ecosystem. Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution 53: 355-370.

- Heithaus, M. R., A. J. Wirsing, J. Thomson, and D. Burkholder. 2008. A reveiew of lethal and non-lethal effects of predators on adult marine turtles. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 356: 43-51.

All photographs copyrighted; Images may be used for educational purposes. For use in other forms contact Mike Heithaus