|

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE ISOPERIMETRIC PROBLEM OF QUEEN DIDO

AND ITS MATHEMATICAL RAMIFICATIONS

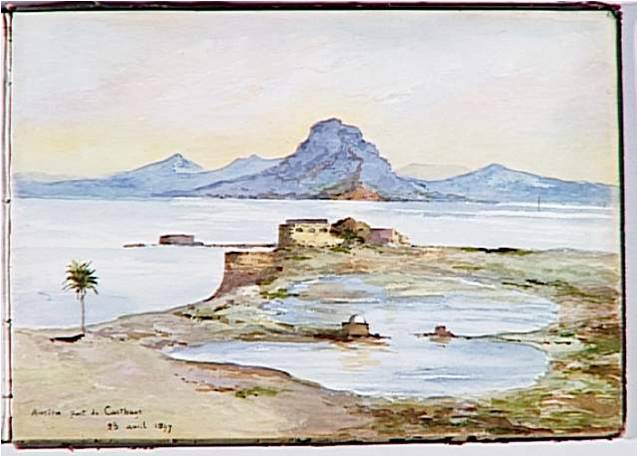

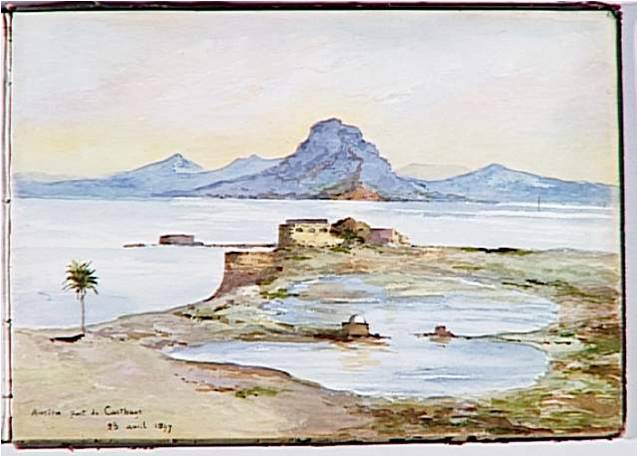

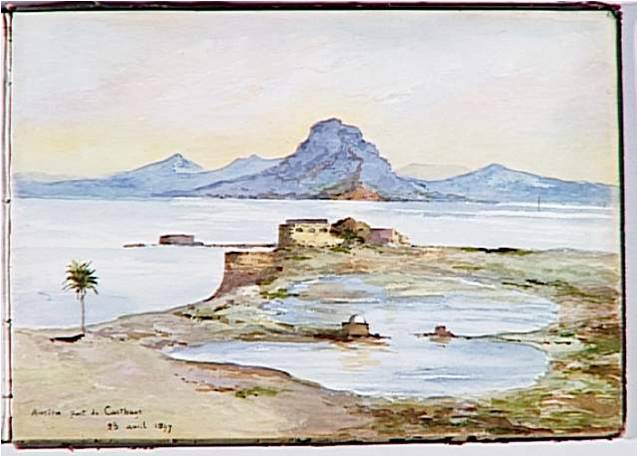

Ancient Mercantile and Military Harbors of

Carthage, with Last Vestiges of the City's Mighty Ramparts,

23 April 1897.

Dido and Isoperimetry

by Mark Ashbaugh and Rafael Benguria

|

Didon et l'isopérimétrie

traduction de Jacqueline Fleckinger-Pellé

|

|

The subject of isoperimetry has a long and eventful history, both for its impact on people's imaginations and society in general and

for the impetus it has given to the study of various mathematical subjects.

The subject of isoperimetry has a long and eventful history, both for its impact on people's imaginations and society in general and

for the impetus it has given to the study of various mathematical subjects.

Isoperimetry began with the problem confronted by Queen Dido, which was to find the shape of the boundary that should be laid

down (using strips of oxhide) to enclose maximum area. If one assumes a straight coastline, then the answer, which was by all

appearances discovered by Queen Dido, is to lay down the hide in the shape of a semi-circle.

One finds the problem of Queen Dido colorfully described, including various embellishments of the basic problem, in the expository

account that Lord Kelvin gave in 1893. If one takes account that land

may vary in value, or that the coastline may be irregular, one can arrive at various more complicated problems. In a much more

recent exposition, Hildebrandt and Tromba, in their book The Parsimonious Universe: Shape and Form in the Natural World

(originally published as Mathematics and Optimal Form), give a much more detailed account of isoperimetric problems and their

recurrence throughout history. In particular, it is interesting to see how many walled cities in the Middle Ages were constructed to have

a nearly circular perimeter, or to see in general that the growth of many cities gave them a nearly circular form.

On the mathematical side, we find already in Euclid (around 300 BC) the proof that among

rectangles of a given perimeter the one having the greatest area is the square. Also, various writers from antiquity speculated on optimal properties of the honeycombs of bees. When Thomas Hales proved in 2001 that regular hexagons provide a least-perimeter way to partition the plane into unit areas, it was the longest standing open problem in mathematics. As for 3D, Lord Kelvin proposed a solution consisting of relaxed, 14-sided, truncated octahedra. In 1994 D. Weaire and R. Phelan disproved Kelvin's conjecture by providing a new candidate using both 12- and 14-sided shapes.

Among the ancient Greeks who worked on the isoperimetric problem we mention

Zenodorus (c. 200 - c. 140 BC) who wrote a now-lost treatise On Isoperimetric Figures

and Ptolemy (c. 90 - c. 168 AD). It is thanks to Theon of Alexandria (c. 335 - c. 405 AD) who wrote a commentary on the work of Ptolemy that we know the results of Zenodorus. Al-Kindi, an Arab mathematician and the son of one of their kings, wrote in the 9th century A Treatise on Isoperimetric Figures and Isepiphanies, that is solids of given surface. There is also a lost treatise by al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham (965 - c. 1039). Abu Ja'far al-Khazin, commenting on Ptolemy's Almagest in the 10th century, generalized earlier works. Johannes de Sacrobosco

(John of Holywood, c. 1195 - c. 1256 AD), an English scholar and astronomer, wrote

Tractatus de Sphaera. A commentary on this treatise, dealing specifically with isoperimetry, can be found in Two New Sciences of Galileo Galilei published in 1638.

The mathematical study of the isoperimetric problem and related problems really began to take off with the advent of calculus, when

people like Newton, Leibniz, the Bernoullis, and others developed systematic ways of attacking optimization problems based on the

calculus, and within a few short years were attacking problems in the calculus of variations (that is, the problem of finding an optimizing

path or shape of curve from among some class of curves). For example, the brachistochrone problem was formulated by Johann

Bernoulli and solved by Newton and both Bernoulli brothers, Jakob (James) and Johann (John). In the same period, the problem of the

shape of a hanging chain (the catenary) was posed and solved, and Newton considered the shape of projectile which would give the

least air resistance (the question of designing the optimal shape for the nose-cone of a rocket or missile), but without reaching definitive conclusions. Others, including US President Thomas Jefferson, considered questions such as the optimal shape for ploughshares.

In the century following the early development of calculus by Newton, Leibniz, the Bernoulli brothers, and others, the calculus of

variations was brought to a relatively advanced state, especially from the point of view of direct solutions of problems, by Euler and

Lagrange. The explicit solution of the classical isoperimetric problem could be derived in those terms (using variational theory with a

constraint), and many other problems could be formulated and solved. ... (click here to read the full essay)

|

Le sujet de l'isopérimétrie a une longue et riche histoire, à la fois pour son impact sur l'imagination populaire et plus généralement sur celle de la société et aussi pour l'élan qu'il a donné à l'étude de sujets mathématiques variés.

Le sujet de l'isopérimétrie a une longue et riche histoire, à la fois pour son impact sur l'imagination populaire et plus généralement sur celle de la société et aussi pour l'élan qu'il a donné à l'étude de sujets mathématiques variés.

L'isopérimétrie a débuté avec le problème auquel a été confrontée la Reine Didon, qui a du trouver la forme de la frontière à poser au sol (en utilisant des bandes de peau de boeuf) pour encercler une surface d’aire maximale. Si l'on suppose la côte droite, alors la réponse, qui a manifestement été trouvée par la Reine Didon, est de poser ces bandes en forme de demi-cercle.

On trouve le problème de la Reine Didon décrit dans

l'exposé imagé qu'en fit Lord Kelvin en 1893, avec plusieurs enrichissements du problème original.

Si l'on prend en compte le fait que la valeur de la terre peut varier, ou que la côte peut être irrégulière, on peut arriver à des problèmes plus complexes. Dans un exposé beaucoup plus récent, Hildebrandt et Tromba, dans leur livre The Parsimonious Universe: Shape and Form in the Natural World (publié initialement comme Mathematics and Optimal Forms), donnent une liste beaucoup plus détaillée des problèmes isopérimétriques et de leur récurrence tout au long de l'histoire. En particulier, il est intéressant de voir combien de cités fortifiées moyenâgeuses ont des

remparts à peu près circulaires ou de regarder plus généralement comment l'extension de beaucoup de villes leur donne une forme circulaire.

Du point de vue mathématique, on trouve dans Euclide la démonstration que parmi les rectangles d'un périmètre donné, celui ayant l'aire maximale est le carré. Par ailleurs, plusieurs écrivains de l'antiquité savaient (du moins spéculaient) que les rayons de miel des abeilles, de forme hexagonale, étaient optimaux pour utiliser le moins de matériel pour la construction d’un treillis de cellules, chaque cellule contenant un volume fixe.

L'étude mathématique du problème isopérimétrique et des problèmes associés a commencé réellement avec le développement du calcul, quand des gens comme Newton, Leibniz, les Bernoulli, et d'autres ont établi des méthodes systématiques, basées sur le calcul, pour attaquer ces problèmes d'optimisation, et en quelques années se sont attaqués aux problèmes de calcul de variations (c'est -dire le problème de trouver un chemin optimal ou une forme de courbe parmi une classe de courbes). Par exemple, le problème de brachistochrone a été formulé par Johan Bernoulli et résolu par Newton et les deux frères Bernoulli, Jakob (James) et Johann (John). A la même période, le problème de la forme d'une chaîne suspendue (les caténaires) a été posé et résolu et Newton a considéré la forme d'un projectile présentant le moins de résistance à l'air (détermination de la forme optimale d'un nez de cône de fusée ou de missile), mais sans obtenir de conclusions définitives. D'autres, et parmi eux le Président Thomas Jefferson, ont étudié de telles questions, par exemple la forme optimale du soc de charrue.

Au siècle suivant, avec les premiers développements de calcul par Newton, Leibniz, les frères Bernoulli et d'autres, le « calcul des variations » a atteint un stade relativement avancé, surtout pour le calcul des solutions obtenu par Euler et Lagrange. La solution explicite du problème classique isopérimétrique pouvait ainsi s'en déduire (en utilisant le calcul variationnel avec une contrainte), et de nombreux problèmes pouvaient ainsi être formulés et résolus. Euler et Lagrange ont montré que tous les problèmes de mécanique peuvent être mis dans ce cadre et que de nombreux problèmes de physique et de mathématique peuvent être vus sous le jour de principes variationnels ou d'optimisation (par exemple le principe de Fermat -moindre temps-, ou, plus généralement le principe de moindre action de d'Alembert/Maupertuis, principe pour lequel Euler a donné une formulation définitive). Un siècle plus tard environ, Jacobi et Hamilton ont aussi apporté d'importantes contributions à ce domaine, principalement en mécanique.

Au 19ème siècle, Jakob Steiner s'est attaqué au problème classique de l'isopérimétrie par des méthodes géométriques très suggestives et instructives et qui ont conduit à de nombreux développements ultérieurs.

... (cliquer ici pour le texte integral)

|

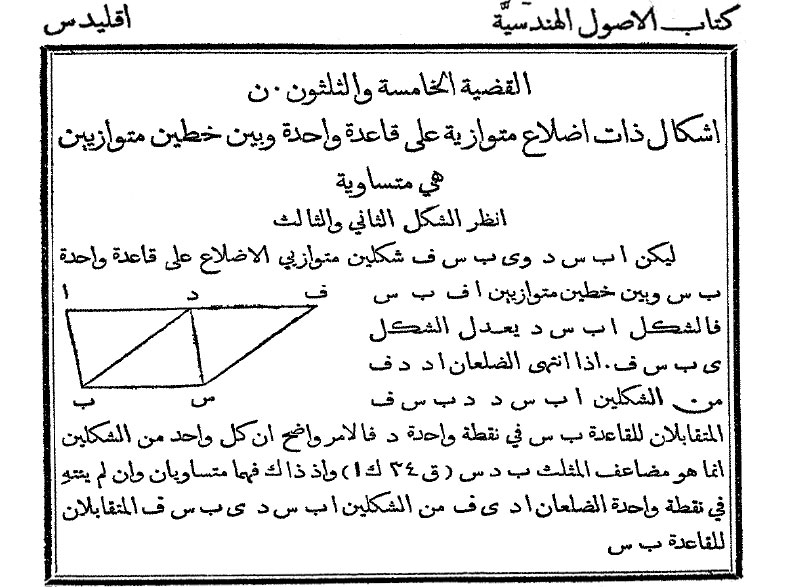

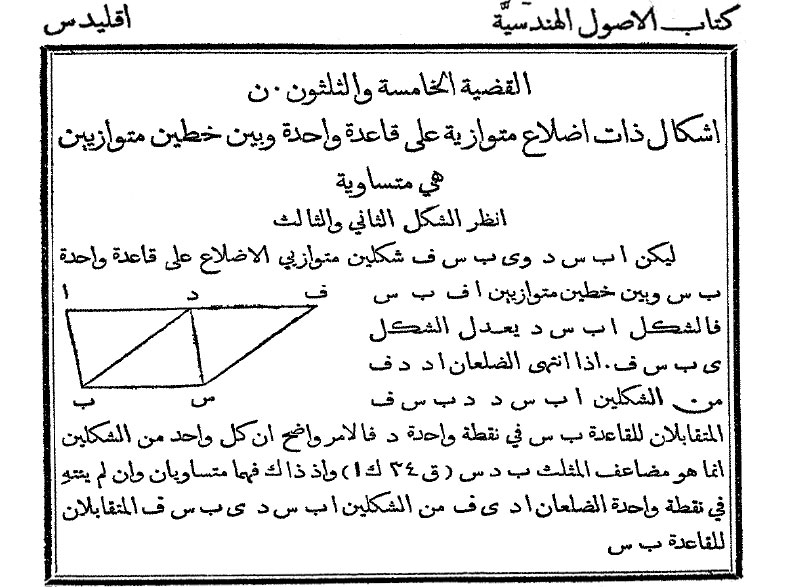

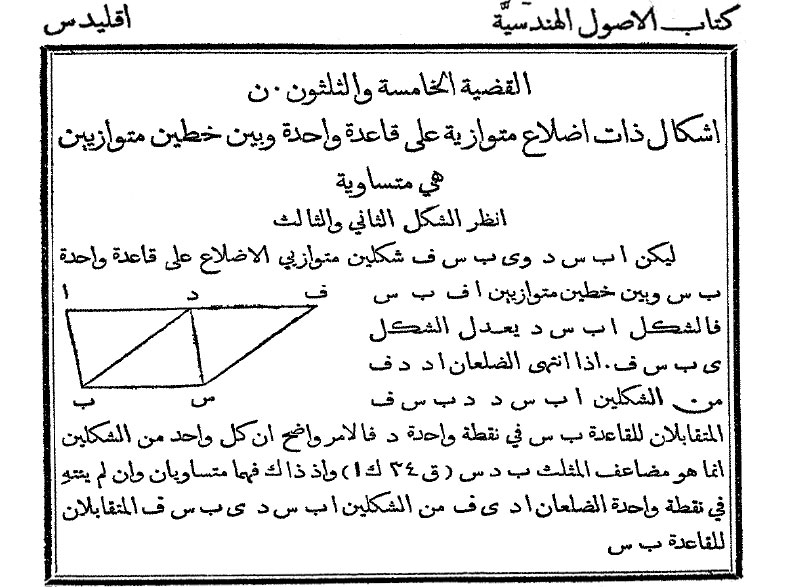

EUCLID (c. 365-300 BC):

Elements, I, 35-38: Two parallelograms,

or triangles, which are on the same base, or on

equal bases, and in the same parallels, remain equivalent in area,

no matter how far the sides between the parallels may be stretched

out and increase in their length. (Comments from

Solomon Gandz's classical

article: "Studies in Babylonian Mathematics III: Isoperimetric Problems and the Origin of the Quadratic

Equations", Isis, Vol. 32, July 1940, pp. 103-115.) The detailed proof is offered

from a modern Arabic translation of Euclid's Elements by Cornelius Van Dyck al-Amrikani (1819-1895) in a

Syrian edition of 1916 AD. For a more classical translation, check the Harvard Library (1812 version

published by the official press of the Ottoman State.)

|